Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption (34 page)

Read Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption Online

Authors: Laura Hillenbrand

Tags: #Autobiography.Historical Figures, #History, #Biography, #Non-Fiction, #War, #Adult

“Marlene Dietrich!”

Louie backed away, waiting for the Weasel to burst out. Several other guards went into the guardhouse, and Louie could hear laughing. The Weasel never punished Louie, but the next time he needed a shave, he went elsewhere.

——

For the captives, every day was lived with the knowledge that it could be their last. The nearer the Al ies came to Japan, the larger loomed the threat of the kil -al order. The captives had only a vague idea of how the war was going, but the Japanese were clearly worried. In an interrogation session in late spring, an official told Fitzgerald that if Japan lost, the captives would be executed. “Hope for Japan’s victory,” he said. The quest for news of the war took on special urgency.

One morning, Louie was on the parade ground, under orders to sweep the compound. He saw the Mummy—the camp commander—sitting under a cherry tree, holding a newspaper. He was nodding off. Louie loitered near him, watching. The Mummy’s head tipped, his fingers parted, and the paper fluttered to the ground. Louie swept his way over, reached out with the broom, and, as quietly as he could, forked the newspaper to himself. The text was in Japanese, but there was a war map on one page. Louie ran to the barracks, found Harris, and held the paper up before him. Harris stared at it, memorizing the map. Louie then ran the paper to the garbage so they’d have no evidence of the theft. Harris drew a perfect rendering of the map, showed it to the other captives, then destroyed it. The map confirmed that the Al ies were closing in on Japan.

In July, the scuttlebutt in camp was that the Americans were attacking the critical island of Saipan, in the Mariana Islands, south of mainland Japan. A spindly new captive was hauled in, and everyone eyed him as a source of information, but the guards kept him isolated and forbade the veterans from speaking to him. When the new man was led to the bathhouse, Louie saw his chance. He snuck behind the building and looked in an open window. The captive was standing naked, holding a pan of water and washing as the guard stood by. Then the guard stepped away to light a cigarette.

“If we’ve taken Saipan, drop the pan,” Louie whispered.

The pan clattered to the floor. The captive picked it up, dropped it again, then did it a third time. The guard rushed back in, and the captive pretended that the pan had accidental y slipped.

Louie hurried to his friends and announced that Saipan had fal en. At the time of their capture, the American bomber with the longest range was the B-24. Because the Liberator didn’t have the range to make the three-thousand-mile round-trip between Saipan and Japan’s home islands, the captives must have believed that winning Saipan was only a preliminary step to establishing an island base within bomber range of mainland Japan. They didn’t know that the AAF had introduced a new bomber, one with tremendous range. From Saipan, the Japanese mainland was already within reach.

The guards and officials were increasingly agitated. Sasaki had long crowed about the inevitability of Japan’s victory, but now he buddied up to the captives, tel ing Louie of his hatred of former prime minister and war architect Hideki Tojo. He began to sound like he was rooting for the Al ies.

As they considered the news on Saipan, Louie and the others had no idea what horrors were attending the Al ied advance. That same month, American forces turned on Saipan’s neighboring isle, Tinian, where the Japanese held five thousand Koreans, conscripted as laborers. Apparently afraid that the Koreans would join the enemy if the Americans invaded, the Japanese employed the kil -al policy. They murdered al five thousand Koreans.

At night, as they lay in their cel s, the captives began hearing an unsettling sound, far in the distance. It was the scream of air-raid sirens. They listened for bombers, but none came.

——

As summer stretched on, conditions in Ofuna declined. The air was clouded with flies, lice hopped over scalps, and wiggling lines of fleas ran the length of the seams in Louie’s shirt. Louie spent his days and nights scratching and slapping, and his skin, like that of everyone else, was speckled with angry bite marks. The Japanese offered a rice bal to the man who kil ed the most flies, inspiring a cutthroat swatting competition and hoarding of flattened corpses.

Then, in July, the men were marched outside and into a canal to bail water into rice paddies. When they emerged at the day’s end, they were covered in leeches. Louie had six on his chest alone. The men became frantic, begging the guards for their cigarettes. As they squirmed around, jabbing at the leeches with cigarettes, one of the guards looked down at them.

“You should be happy in your work,” he said.

On August 5, a truck bearing the month’s rations arrived. As Fitzgerald watched, camp officials stripped it nearly clean. Curley announced that the rations were again being cut, blaming it on rats. Fitzgerald noted in his diary that after officials were done “brown bagging” their way through the seventy pounds of sugar al otted to the captives, one teacup of sugar remained. On August 22, a truck backed up to the kitchen door, and the captive kitchen workers were told to leave. Fitzgerald went to the benjo, from which he could see the kitchen. He saw sacks of food being piled into the truck, which then left camp. “Someone must be opening up a store and real y getting set up in business,” he wrote.

The beatings went on. The Quack was especial y feral. One day, Louie saw some Japanese dumping fish into the trough in which the captives washed their hands and feet. Told to wash the fish, Louie walked up and peered into the trough. The fish were putrid and undulating with maggots. As he recoiled, the Quack saw him, pounded over, and punched him a dozen times. That night, the same fish was ladled into Louie’s bowl. Louie wouldn’t touch it. A guard jabbed him behind the ear with a bayonet and forced him to eat it.

And then there was Gaga. Something about this affectionate little duck, perhaps the fact that he was beloved to the captives, provoked the guards.

They tortured him mercilessly, kicking him and hurling him around. Then one day, in ful view of the captives, Shithead opened his pants and violated the bird. Gaga died. Of al the things he witnessed in war, Louie would say, this was the worst.

Louie’s mind fled Ofuna and carried him home. He hadn’t seen his family in two years. He thought of the little white house, Virginia and Sylvia, his father and dear, devoted Pete. Most poignant were his memories of his mother. Fred Garrett had told Louie that he’d been given up for dead. Louie couldn’t bear the thought of what this news must have done to his mother.

It was the accumulation of so much suffering, the tug of memory, and the conviction that the Japanese wouldn’t let them leave Ofuna alive that led Louie to listen to the nearby planes and wonder if they could be a way out. Examining the fence, he, Tinker, and Harris concluded that it might be possible to get around the guards and over the barbed wire. The thought hooked al three of them. They decided to make a run for it, commandeer a plane, and get out of Japan.

——

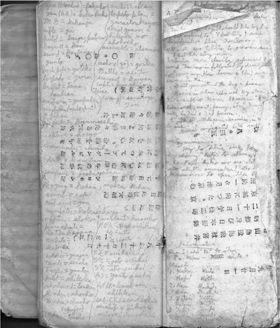

At first, their plans hit a dead end. They’d been brought in blindfolded and had ventured out of camp only briefly, to irrigate the rice paddies, so they knew little about the area. They didn’t know where the airport was, or how they’d steal a plane. Then a kind guard inadvertently helped them. Thinking that they might enjoy looking at a book, he gave them a Japanese almanac. Harris cracked it open and was immediately rapt. The book was ful of detailed information on Japan’s ports, the ships in its harbors and the fuels they used, and the distances between cities and landmarks. It was everything they needed to craft an escape.

In hours spent poring over the book, they shaped a plan. They discarded the plane idea in favor of escape by boat. Just a few miles to the east was the port of Yokohama, only there was nowhere to go from there. But if they crossed Japan to the western shore, they could get to a port that would offer a good route to safety.

They’d go on foot. Harris plotted a path across the island, a walk of about 150 miles. It would be dangerous, but Harris’s earlier experience of hiking al over the Bataan Peninsula gave them confidence. Once at a port, they’d steal a powerboat and fuel, cross the Sea of Japan, and flee into China. Given that Louie had drifted two thousand miles on a hole-riddled raft with virtual y no provisions, a few hundred miles on the Sea of Japan in a sturdy powered boat seemed manageable. Tinker, who’d been captured more recently than Harris and Louie, had the most current knowledge of which areas of China were occupied by the enemy. He worked out a route that they hoped would steer them clear of the Japanese.

They counted on finding safe harbor in China. In 1942, America had launched its first and, until recently, only bombing raid on Japan’s home islands.

The raid had used B-25s flown, perilously, off an aircraft carrier, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle. After bombing Japan, some of the Doolittle crews had run out of gas and crashed or bailed out over China. Civilians had hidden the airmen from the Japanese, who’d ransacked the country in search of them. Harris, Tinker, and Louie had heard rumors that the Japanese had retaliated against Chinese civilians for sheltering the Doolittle men, but didn’t know the true extent of it. The Japanese had murdered an estimated quarter of a mil ion civilians.

There was one problem that the men didn’t know how to overcome. When they stood near the guards, it was impossible not to notice how much the Americans differed from typical Japanese people, and not simply in facial features. The average Japanese soldier was five foot three. Louie was five foot ten, Tinker six feet, Harris even tal er. Hiking across Japan, they’d be extremely conspicuous. China might be welcoming, but in Japan, it would be foolish to assume that they’d find friendly civilians. After the war, some POWs would tel of heroic Japanese civilians who snuck them food and medicine, incurring ferocious beatings from guards when they were caught. But this behavior was not the rule. POWs led through cities were often swarmed by civilians, who beat them, struck them with rocks, and spat on them. If Louie, Harris, and Tinker were caught, they would almost certainly be kil ed, either by civilians or by the authorities. Unable to remedy the height difference, they decided to move only at night and hope for the best. If they were going to die in Japan, at least they could take a path that they and not their captors chose, declaring, in this last act of life, that they remained sovereign over their own souls.

As the plan took shape, the prospective escapees walked as much as possible, strengthening their legs. They studied the guards’ shifts, noting that there was a patch of time at night when only one guard watched the fence. Louie stole supplies for the journey. His barber job gave him access to tools, and he was able to make off with a knife. He stole miso paste and rice. He gathered bits of loose paper that flitted across the compound, to be used for toilet paper, and every strand of loose string he could find. He stashed al of it under a floorboard in his cel .

For two months, the men prepared. As the date of escape neared, Louie was fil ed with what he cal ed “a fearful joy.”

Just before the getaway date, an event occurred that changed everything. At one of the POW camps, a prisoner escaped. Ofuna officials assembled the men and issued a new decree: Anyone caught escaping would be executed, and for every escapee, several captive officers would be shot. Louie, Tinker, and Harris suspended their plan.

——

With the escape off, Louie and Harris channeled their energy into the captive information network. At the beginning of September, a captive saw a newspaper lying on the Quack’s desk. There was a war map printed in it. Few things were more dangerous than stealing from the Quack, but given the

threat of mass executions upon an Al ied invasion, the captives were wil ing to do almost anything to get news. Only one man had the thieving experience for a job this risky.

For several days, Louie staked out the Quack’s office, peeking in windows to watch him and the guards. At a certain time each day, they’d go into the office for tea, walk out together to smoke, then return. The length of their cigarette break never varied: three minutes. This was Louie’s only window of opportunity, and it was going to be a very, very close cal .