Ultramarathon Man (25 page)

Authors: DEAN KARNAZES

Gaylord passed the big runner on his way to the summit.

“Your friend's having a tough go of it, eh?” the big guy asked Toph.

“He's hurting pretty good, all right,” Gaylord replied.

“What team is he on? We didn't know anyone was in front of us.”

“Actually, he's not on a team. He's running solo.”

“You're shittin' me. That's insane. Who is he?”

“His name is Dean.”

Crew vehicles had begun to pull into the exchange area when Gaylord got to the top. They were colorfully decorated, some with team mascots or stuffed figures on their roofs. The big guy was a member of the Berkeley Rugby Team alumni; they were driving a full-sized school bus, purportedly with two kegs inside. A bumper sticker on the back declared GIVE BLOODâPLAY RUGBY.

As I crested the summit and wobbled around the corner, I encountered eleven of the gnarliest-looking thugs I'd ever seen. The big guy, the human refrigerator who'd passed me coming up the hill, was at their head. He had on a Viking helmet and a full-length fur coat with only a pair of running shorts underneath. In his hand was a pitcher of ale. It was 7:00 A.M.

The rugby dudes started chanting as I slogged by. “Team Dean. Team Dean! TEAM DEAN!”

It was an odd moment, but an inspirational one. And that is how my team earned its name. I say

earned

because you don't get a squadron of bad-ass rugby players lining the road cheering by doing something marginally inspirational. There was a good measure of manly honor that came with that moniker “Team Dean.”

earned

because you don't get a squadron of bad-ass rugby players lining the road cheering by doing something marginally inspirational. There was a good measure of manly honor that came with that moniker “Team Dean.”

Filled with testosterone, I ran down the back side of the summit with blazing speed. The pounding seemed a little less severe, and the effort running down the mountainside was far less taxing than the climb up. It would be a stretch to say I was experiencing a “runner's high,” but it was a temporary absence of radiating pain, which, at this point, was about the best I could hope for.

Jamming down the mountain's back, Gaylord in tow, I was averaging better than seven-minute miles, which was absurdly fast after having run 170 miles. But it felt right, so I just went with it and didn't ask questions.

In relative terms, I'd covered five-sixths of the course. Santa Cruz was now just some 30 miles away. But in absolute terms, it may as well have been on the other side of the universe. My success was far from assured. Even in my revived state, 30 miles is no small distance, especially after having run 170.

The Mother Ship came barreling along, emitting honks and cheers and unintelligible screams. Beautiful music to me. I waved and smiled and flashed a thumbs-up, and they sped off to the next exchange.

Gaylord pedaled on as well. “Need anything ahead?” he asked.

“Some Pedialyte would be great.”

“Infant formula?”

“Mother's milk,” I replied. “Works wonders.”

They were waiting for me at the exchange with Pedialyte and cheers.

“Go, Team Dean,” Gaylord joked.

“GO, TEAM DEAN!” my family chimed in.

I grabbed the Pedialyte and ran on. The road forked, and I kept running straight. And I continued running, and running . . . and then realized after about half a mile that no one else was around. I stopped and looked back. No teams behind me, no crew vehicles. Had I entered the Twilight Zone?

Then it occurred to me that in my glee perhaps I had gone the wrong way at the fork. I'd gone straight and was on Highway 236; the course route had bent left and was on Highway 9.

Turning around, I asked myself,

What's one extra mile?

But that mistake marked another swing in my disposition. The half-mile back to the junction was demoralizing.

How could I make such a stupid mistake?

What's one extra mile?

But that mistake marked another swing in my disposition. The half-mile back to the junction was demoralizing.

How could I make such a stupid mistake?

By the time I reached the next exchange, I was in a terrible funk. My speech was slurred, and I was trembling badly from hypoglycemia.

“What happened?” my dad asked. “Where did you go?”

I could only shake my head in despair. They had set up a chair and I slumped into it, arms dangling. The kids were firing questions, but I was too despondent to reply. A small crowd of runners assembled around me.

“Are you

Team Dean

?” someone asked.

Team Dean

?” someone asked.

I couldn't answer for a long, awkward moment. And then I said softly, “Yes, I am Team Dean.”

It was the first time I'd said it. And despite my forlorn state, it felt good. It reminded me exactly why I was out here running for two days straight. I was doing it because I could; it was my place in the world.

I wasn't born with any innate talent. I've never been naturally gifted at anything; I always had to work at it. The only way I knew to succeed was to try harder than anyone else. Dogged persistence is what got me through life. But here was something I was half-decent at. Being able to run great distances was the one thing I could offer the world. Others might be faster, but I could go longer. My strongest quality is that I never give up. Running as far as possible was one activity where being stubborn as a bull was actually a good thing. It suited my personality.

“Yep,” I said, more energetically. “Team Dean here!”

“We think what you're doing is incredible,” one runner said.

“You mean the men in white suits aren't coming to take me away?”

My attempt at a joke broke the tension, and the crowd began to loosen up.

“Hey, Team Dean,” another runner shouted, “what's on the menu for breakfast, a box of nails?”

The crowd laughed, and I did, too. Mine went on for a while, with good reason. It was one of those rare moments in life where everything is perfect.

Everything, except for the 23.7 miles still left to cover.

Â

Â

Â

Exiting exchange 32,

I knew that the next 23.7 miles would probably be both the most glorious and the most hideous of my life. It was going to be an epic struggle, an all-out battle to reach the finish. The game was getting good. I just hoped the ending would be happy.

I knew that the next 23.7 miles would probably be both the most glorious and the most hideous of my life. It was going to be an epic struggle, an all-out battle to reach the finish. The game was getting good. I just hoped the ending would be happy.

Within a mile of leaving the exchange, I found myself flagging again; the high of twelve minutes ago was replaced by a feeling of desolation. The cumulative miles were taking their toll, and I ran along to the best of my impaired ability, trying to suppress the overwhelming desire to stop and lie down.

As you progress in a long race, your highs become higher and your lows lower, and the fluctuations come with escalating rapidity. It was like squeezing the emotional drama of a lifetime into two days. All I consciously thought about was getting to the finish line, and the mood swings came unexpectedly, without warning. There was no controlling the onset, no way of knowing when a funk would strike. It just happened.

The Mother Ship zoomed by with muffled cheers and disappeared around a bend. Sweat was pouring down my unshaven face as I strained to wave.

Then Gaylord rolled up beside me. “Karno, how's it going?”

“I've hit a new low, Toph.”

“I can't even imagine what it feels like to run this far.”

I thought a moment. “Want a taste of it? Bail the bike and run with me.”

“Now? But I've never really run before.”

“It's not very tricky. You'll figure it out pretty quick.”

We caught up with the Mother Ship around the bend, and before he could react I announced, “Gaylord's going to run with me.” We stored the bike with them, refilled my bottles with ice-cold Pedialyte, and the two of us set out together.

Gaylord handled the first half-dozen miles admirably but was pretty tooled by mile 7. If there's one thing that can ease your own personal suffering, it's the sight of someone else suffering even worse. Yet he kept pushing alongside me, not willing to drop back.

“Do you want to slow down?”

“You kidding?” he groaned. “I'm loving this.”

After eight torturous miles, we caught up with the Mother Ship again, and it wasn't hard to convince Gaylord to end his run there. He was exhausted, yet there was something in his voice that said running wasn't entirely disagreeable, no matter how much it hurt. I had a funny feeling this might not be the last time he laced up a pair of running shoes.

It was just as well he packed it in for now. Around the corner was a seriously stout climb that would challenge a seasoned runner even under ideal conditions. Gaylord had just run more miles in an hour than he had logged cumulatively in the past ten years. Scaling an 1,180-foot incline in temperatures now approaching 90 degrees would've been ill-advised. Not that I was any better equipped to deal with the hill than he was at this point.

The kids squirted water at me with their sprayers as I sauntered by.

“Darling, why don't you stop and eat,” Mom offered.

“Don't slow him down,” Dad rebuffed her. “He's looking strong.” Meanwhile I was about to keel over from lack of nourishment. .

“Wait! Wait! . . .”

I mumbled as they blasted off to the next exchange station, not hearing my feeble pleas.

I mumbled as they blasted off to the next exchange station, not hearing my feeble pleas.

The climb out of Felton to Empire Grade has rightly been called “Killer.” At points the pitch is so severe that even walking it is a strain. My quadriceps and calves burned in agony. The arteries, veins, and even small capillaries in my arms and legs protruded under my glistening skin like exposed roots. All systems were being pushed beyond their functional limit.

The human body is capable of extraordinary feats of endurance, but it has protective mechanisms to prevent total annihilation. Typically the system will shut down before physical destruction occurs. Blacking out is the body's ultimate act of self-preservation. When you're teetering on the edge of coherenceâwhich running 185 miles can induceâstepping over the edge becomes a very real threat. One minute you're running, the next you're in the back of an ambulance heading for the ER.

Marching up the hill in a catatonic stupor, I began to experience a peculiar floating sensation, as though my body had dissociated from my mind. All I could sense of my legs was a vague tingling sensation in my lower torso, and I floated along barely coherent. There was a pesky string of drool dangling off my chin, swinging from side to side with every forward lunge, and my pace slowed to a crawl. A complete meltdown was in progress; I was falling apart.

And then a perky little voice cheered, “Way to go, Team Dean!”

It was a stunning young TV reporter, leaning out of the side of a rolling van, and behind her a camera was trained on me.

“You look great,” she said. “Are you feeling all right?”

The dribble still hung from my chin, and I wondered if she'd understand what the kids and I called caveman language. We'd developed it while I did push-ups on the living room floor with both of them on my back. It was an extremely simple language: one grunt meant

yes,

two grunts

no.

yes,

two grunts

no.

I grunted twice.

“Excuse me?” she replied.

So much for caveman language. I struggled for words and came up with, “Still standing.”

“Well, that's good,” she chirped. “Can you give us some thoughts on how things have gone?”

“Ah . . . so far, so good,” I puffed. “Check back with me in a few minutes, though. It might be a different story by then.”

“Sounds like Team Dean is doing just fine,” she told the camera spiritedly. “We'll check back with him shortly. Stay tuned.”

With the camera off, she asked if there was anything they could get for me.

“Have access to a jet pack?” I huffed. “It'd be kind of nice to levitate to Santa Cruz.”

She gave me a quizzical look and they sped off up the hill to scout another location.

Â

Â

Â

“Where's your

next runner?” the exchange captain asked as I dragged myself up into the next, and next-to-last, relay point near the top of the climb. Winded and unable to lift my head, I muttered, “Don't have one.”

next runner?” the exchange captain asked as I dragged myself up into the next, and next-to-last, relay point near the top of the climb. Winded and unable to lift my head, I muttered, “Don't have one.”

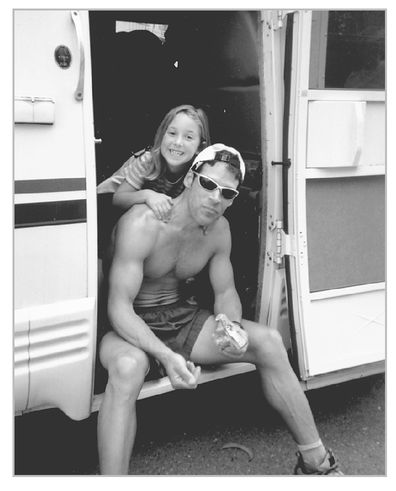

Brief reprieve with Alexandria at the Mother Ship, mile 188

“Ohh . . . you must be Team Dean. We were wondering if you were still alive.”

“That's debatable,” I panted.

“Yes, it's Team Dean,” chimed in a voice I recognized as my father's, “and he's doing fine. Now, let's get moving, son.”

“I need a break.”

“Our people are great runners,” he proclaimed to no one in particular. “We ran all day through the hills of Greece chasing mountain goats.”

“Pops,” I reminded him, “we grew up in L.A.”

Alexandria began misting me with her spray bottle. Nicholas, on the other hand, squirted a shocking jet of ice water into my ear. “Hey!” I hollered, chasing him around the relay station to the amazement of onlookers.

Other books

Conan and the Shaman's Curse by Sean A. Moore

El Paseo by Federico Moccia

The Division of the Damned by Richard Rhys Jones

Thunder On The Right by Mary Stewart

Vicky Banning by McGill, Allen

Betrayal with Murder (A Rilynne Evans Mystery, Book Three) by Vakey, Jenn

Crimson Joy by Robert B. Parker

Three Original Ladies 02 - Lord Trowbridge’s Angel by G.G. Vandagriff

The Party: The Secret World of China's Communist Rulers by Richard McGregor

Present Tense (A Parker & Coe, Love and Bullets Thriller Book 2) by Matthews, Alana