Tyrant: King of the Bosporus (2 page)

E

umeles sat at a plain table on a stool made of forged iron, his long back as straight as the legs on his stool and his stylus moving quickly over a clean tablet. He pursed his lips when he inscribed a sloppy sigma in the red wax, and he rubbed it out fastidiously and went back to writing his list of requirements.

Most of his requirements had to do with money.

‘The farmers are not used to a direct tax,’ Idomenes, his secretary, said.

Eumeles glared at him. ‘They’d best get used to it. This fleet is costing me everything in the treasury.’

Idomenes was afraid of his master, but he set his hip as if he was wrestling. ‘Many won’t pay.’

‘Put soldiers to collecting,’ Eumeles said.

‘Men will call you a tyrant.’

‘Men already call me a tyrant. I

am

a tyrant. I need that money. See that it is collected. These small farmers need some of the independence crushed out of them. We would grow more grain if we pushed out the Maeotae and used big estates – like Aegypt.’

Idomenes shrugged. ‘Traditionally,

my lord

, we have taxed the grain as it went on the ships.’

‘I did that, as you well know. That money was spent immediately. I need more.’ Eumeles looked up from his tablet. ‘I’ve really had enough of this. Simply obey.’

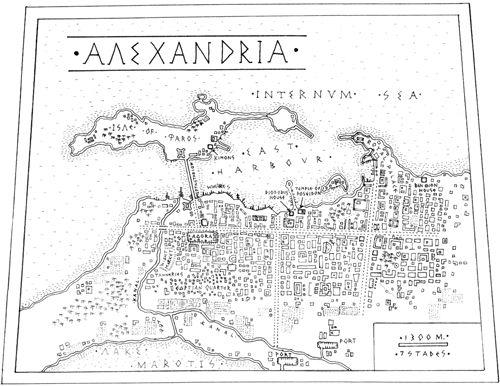

Idomenes shrugged. ‘As you wish, lord. But there will be trouble.’ The secretary opened the bag at his hip and withdrew a pair of scrolls tied with cord and sealed with wax. ‘The reports from Alexandria. Do you want them today?’

Eumeles pursed his lips again. ‘Read them and give me a precis.

Neither of our people there ever seems to report anything I can

use

. I sometimes wonder if Stratokles didn’t recruit mere gossips.’

Idomenes cracked the wax, unwound the cord and rolled his eyes. ‘Cheap papyrus!’ he commented angrily, as the scroll fragmented under his fingers into long, narrow strips.

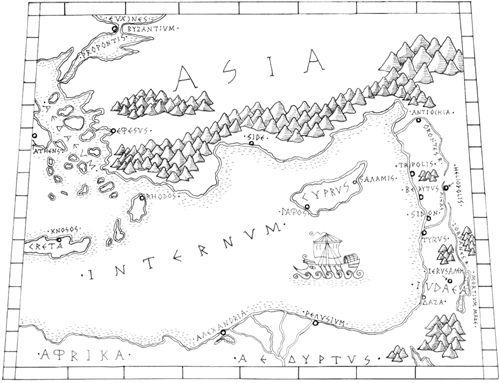

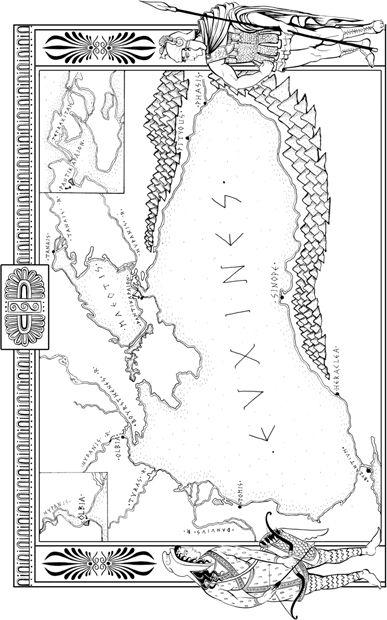

Eumeles grunted. He went back to his lists – headed by his need to hire competent helmsmen to man his new fleet. He needed a fleet to complete the conquest of the Euxine – a set of conquests that would soon leave the easy pickings behind and start on the naval powers, like Heraklea and Sinope, across the sea. And the west coast, which would bring him into conflict with Lysimachos. He feared the wily Macedonian, but Eumeles was himself part of a larger alliance, with Antigonus One-Eye and his son Demetrios. His new fleet had been built with subsidies from One-Eye. And the man expected results.

‘Ooi!’ Idomenes shouted, leaping to his feet. ‘The woman actually has something of value. Goodness – the gods smile on us! Listen: “After the feast of Apollo, Leon the merchant summoned his captains and announced to them that he planned to use his fleet to topple Eumeles, with the approval of the lord of Aegypt. He further announced that he would finance a

taxeis

of Macedonians and a squadron of mercenary warships.” Blah, blah – she names every man at the meeting. Goodness, my lord, she’s quite the worthy agent. There’s a note in the margin – “Diodorus . . .” That name means something? “. . . has the Exiles . . . with Seleucus”?’

Eumeles nodded. He found his fists were clenched. ‘Diodorus is the most dangerous of the lot. Damn it! I thought Stratokles was going to rid me of these impudent brats and their wealthy supporters. It’s like a plague of head lice defeating Achilles. Hardly worthy opponents. So – they’re coming?’

Idomenes checked the scroll, running his fingers down the papyrus. ‘Ares, Lord of War – they may already have sailed!’

‘Why haven’t we read this scroll before?’ Eumeles asked.

‘I see – no – they’ll sail next week. He’s buying a squadron of mercenary captains – Ptolemy’s offcasts.’ Idomenes smiled.

‘Ptolemy will never win this war if he keeps shedding his soldiers as soon as he wins a victory,’ Eumeles commented. ‘He’s the richest contender. Why doesn’t he keep his fleet together?’

Idomenes considered telling his master the truth – that Ptolemy

was rich because he

didn’t

overspend on military waste. But he kept reading. ‘This is their scout. They’re coming before the autumn rains – to raise the coastal cities against you and sink your fleet. The army will come in the spring.’

Eumeles got to his feet and smiled. He was very tall and too thin, almost cadaverous, and his smile was cold. ‘A scout? How nice. Kineas the

strategos

used to say that if you wanted something done well, you had to do it yourself. Send for Telemon.’

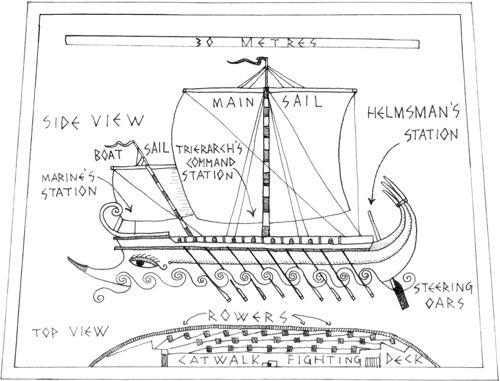

Telemon was one of the tyrant’s senior captains. Idomenes passed the time reading aloud the list of ships from the marginal notes and their captains. ‘Satyrus will command

Black Falcon

.’

‘Some professional helmsman will command. He’s just a boy. Well, may he enjoy the adventure, for he won’t survive it,’ Eumeles said. He called a slave and ordered that his armour be packed for sea.

Telemon swaggered in, announced by another slave. He was a tall man with ruddy cheeks and fair hair.

‘You took your time,’ Eumeles said.

Telemon shrugged. When he spoke, his voice was curiously high-pitched, like a temple singer – or a god in a machine. ‘I’m here,’ he said.

‘Cancel the expedition to Heraklea,’ Eumeles said. ‘Get the fleet ready to sail south.’

‘We’re ready now,’ Telemon intoned. His voice implied that his master wasn’t very bright.

‘Good.’ Eumeles ignored other men’s tones, or had never understood them. Idomenes wondered if his master’s ignorance of other men’s feelings towards him was the secret of his power. He didn’t seem to care that he was ugly, ungainly, single-minded, unsocial and unloved. He cared only for the exercise of power. ‘They’ll come up the west coast. We’ll await them west of Olbia, so that they don’t raise the malcontents in that city.’ The tyrant turned to Idomenes. ‘Contact our people in Olbia and tell them that it is time to be rid of our opponents there.’

‘The assembly?’ Idomenes asked.

‘Simple murder, I think. Get rid of that old lack-wit Lykeles. People associate him too much with Kineas. As if Kineas was such a great king. Pshaw. The fool. Anyway, rid us of Lykeles, Petrocolus and his son, Cliomenedes. Especially the son.’

Idomenes looked at his master as if he’d lost his mind. ‘Our hand will show,’ he said. ‘That city is already close to open war with us.’

‘That city can be treated as a conquered province,’ Eumeles said. ‘Kill the opposition. The assembly will fear us.’

‘Kill them and some new leader might arise,’ Idomenes said firmly. ‘What if a knife miscarries? Then we have one of them screaming for your head.’

‘When Satyrus’s head leaves his body, all the fight will go out of the cities. And we own the Sakje – Olbia needs their grain. Stop fighting shadows and

obey me

.’ Eumeles gave his cold smile. ‘What you really mean is that I’m about to go beyond the law – even the law of tyrants. And you don’t like it. Tough. You are welcome to board a ship and sail back to Halicarnassus whenever you wish.’

Once again, Idomenes was amazed at how his master cared nothing for the feelings of other men, and yet could read them like scrolls.

‘And you got me out of my slave’s open legs for a reason?’ Telemon sang.

‘Spare me,’ Eumeles said. He didn’t even like to listen to bawdy songs, his secretary reflected. ‘Await my pleasure.’

Telemon turned on his heel.

‘Isn’t it enough for you that my enemy is about to put his head on the block?’ Eumeles called, ‘And that after he goes down, I will release you and your wolves to burn the seaboard?’

Telemon stopped. He turned back. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Yes, that is news indeed, lord.’ He grinned. ‘What ship will your enemy be in?’

Idomenes was always happy to have information to share. ‘

Black Falcon

, Navarch,’ he said.

‘

Black Falcon

,’ Telemon sang. ‘Stratokles’ ship. I’ll know him,’ he said.

S

atyrus leaned against the rail of the

Black Falcon

and watched his uncle, Leon the Numidian, arguing with his helmsman, just a boat’s length away. Satyrus waited, looking for a signal, a wave, an invitation – anything to suggest that his uncle had a plan.

Next to him, on his own deck, Abraham Ben Zion shook his head.

‘Where did a pissant tyrant like Eumeles get so many ships?’