Two Scholars Who Were in Our Town and Other Novellas (34 page)

Read Two Scholars Who Were in Our Town and Other Novellas Online

Authors: S. Y. Agnon

Tags: #Short Stories (Single Author), #Fiction, #Jewish

Blessed is he who shall not forsake… / From the Musaf prayer of Rosh HaShanah

.

Malbim / Meir Leibush ben Yehiel Michel Wisser (1809-79), better known by the acronym Malbim, was a Russian rabbi, Hebrew grammar, and Bible commentator

.

He shall shave his head… / Job 1:20

.

Beit Midrash / House of Study

.

Succah / Festival booth used during the holiday of Succot; cf. Lev. 23:42-43

.

Haskalah / The Jewish Enlightenment, 18th–19th century movement that advocated adopting values of the European Enlightenment, pressing for better integration into general society, and increasing education in secular studies

.

Gemara / Talmud; main body of the Oral Law comprising a commentary on the Mishnah

.

Kol Nidre / Solemn opening prayer of Yom Kippur

.

Shema / “Hear O Israel” (Deut. 6:4), central declaration of faith and a twice-daily Jewish prayer; also recited at bedtime

.

Screwy / In Hebrew the dog’s name is

Me’uvat

, meaning broken, damaged, warped, bent (cf. Eccl. 1:15, “A

twisted thing

cannot be made straight…”) – the translation cannot contain all the meanings contained in the name, including a mild hint of sexual perversion

.

Shabbat Nahamu / “The Sabbath of Consolation”, nickname for the Sabbath following the mournful three week Summer period commemorating the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple

.

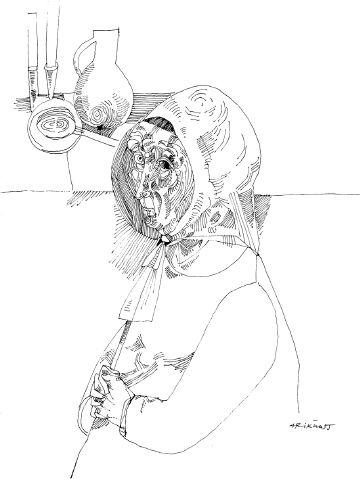

“Now there used to be in Jerusalem a certain old woman, as comely an old woman as you have seen in all your days. Righteous she was, and wise she was, and gracious and humble too: for kindness and mercy were the light of her eyes, and every wrinkle in her face told of blessing and peace.”

Illustration by Avigdor Arikha

N

OW there used to be in Jerusalem a certain old woman, as comely an old woman as you have seen in all your days. Righteous she was, and wise she was, and gracious and humble too: for kindness and mercy were the light of her eyes, and every wrinkle in her face told of blessing and peace. I know that women should not be likened to angels: yet her would I liken to an angel of God. She had in her, moreover, the vigor of youth; so that she wore old age like a mantle, while in herself there was seen no trace of her years.

Until I had left Jerusalem she was quite unknown to me: only upon my return did I come to know her. If you ask why I never heard of her before, I shall answer: why have you not heard of her until now? It is appointed for every man to meet whom he shall meet, and the time for this, and the fitting occasion. It happened that I had gone to visit one of Jerusalem’s celebrated men of learning, who lived near the Western Wall. Having failed to locate his house, I came upon a woman who was going by with a pail of water, and I asked her the way.

She said, Come with me, I will show you.

I replied, Do not trouble yourself: tell me the way, and I shall go on alone.

She answered, smiling: What is it to you if an old woman should earn herself a

mitzva?

If it be a

mitzva

, said I, then gain it; but give me this pail that you carry.

She smiled again and said: If I do as you ask, it will make the

mitzva

but a small one.

It is only the trouble I wish to be small, and not the merit of your deed.

She answered, This is no trouble at all, but a privilege; since the Holy One has furnished His creatures with hands that they may supply all their needs.

We made our way amongst the stones and descended the alleys, avoiding the camels and the asses, the drawers of water and the idlers and the gossip-mongers, until she halted and said, Here is the house of him you seek. I said good-bye to her and entered the house.

I found the man of learning at home at his desk. Whether he recognized me at all is doubtful; for he had just made an important discovery – a Talmudic insight – which he immediately began to relate. As I took my leave I thought to ask him who that woman might be, whose face shone with such peace and whose voice was so gentle and calm. But there is no interrupting a scholar when he speaks of his latest discovery.

Some days later I went again to the City, this time to visit the aged widow of a rabbi; for I had promised her grandson before my return that I would visit her.

That day marked the beginning of the rainy season. Already the rain was falling, and the sun was obscured by clouds. In other lands this would have seemed like a normal day of spring; but here in Jerusalem, which is pampered with constant sunshine through seven or eight months of the year, we think it is winter should the sun once fail to shine with all its might, and we hide ourselves in houses and courtyards, or in any place that affords a sheltering roof.

I walked alone and free, smelling the good smell of the rains as they fell exultantly, wrapping themselves in mist, and heightening the tints of the stones, and beating at the walls of houses, and dancing on roofs, and making great puddles beneath, that were sometimes murky and sometimes gleamed in the sunbeams that intermittently broke through the clouds to view the work of the waters. For in Jerusalem even on a rainy day the sun yet seeks to perform its task.

Turning in between the shops with their arched doorways at the Street of the Smiths, I went on past the spice merchants, and the shoemakers, and the blanket-weavers, and the little stalls that sell hot broths, till I came to the Street of the Jews. Huddled in their tattered rags sat the beggars, not caring even to reach a hand from their cloaks, and glowering sullenly at each man who passed without giving them money. I had with me a purse of small coins, and went from beggar to beggar distributing them. Finally I asked for the house of the

rabbanit

, and they told me the way.

I entered a courtyard, one of those which to a casual passerby seems entirely deserted, and upon mounting six or seven broken stairs, came to a warped door. Outside I bumped into a cat, and within, a heap of rubbish stood in my way. Because of the mist I could not see anyone, but I heard a faint, apprehensive voice calling: Who is there? Looking up, I now made out a kind of iron bed submerged in a wave of pillows and blankets, and in its depths an alarmed and agitated old woman.

I introduced myself, saying that I was recently come from abroad with greetings from her grandson. She put out a hand from under the bedding to draw the coverlet up to her chin, saying: Tell me now, does he own many houses, and does he keep a maidservant, and has he fine carpets in every room? Then she sighed, This cold will be the death of me.

Seeing that she was so irked with the cold, it occurred to me that a kerosene heater might give her some ease: so I thought of a little stratagem.

Your grandson, I said, has entrusted me with a small sum of money to buy a stove: a portable stove that one fills with kerosene, with a wick that burns and gives off much heat. I took out my wallet and said, See, here is the money.

In a vexed tone she answered: And shall I go now to buy a stove, with these feet that are on me? Did I say feet? Blocks of ice I should say. This cold will drive me out of my wits if it won’t drive me first to my grave, to the

Mount of Olives. And look you, abroad they say that the Land of Israel is a hot land. Hot it is, yes, for the wicked in Hell.

Tomorrow, I said, the sun will shine out and make the cold pass away.

“Ere comfort comes, the soul succumbs.”

In an hour or two, I said, I shall have sent you the stove.

She crouched down among her pillows and blankets, as if to show that she did not trust me in the part of benefactor.

I left her and walked out to Jaffa Road. There I went to a shop that sold household goods, bought a portable stove of the best make in stock, and sent it on to the old

rabbanit.

An hour later I returned to her, thinking that, if she was unfamiliar with stoves of this kind, it would be as well to show her the method of lighting it. On the way, I said to myself: Not a word of thanks, to be sure, will I get for my pains. How different is one old woman from another! For she who showed me the way to the scholar’s house is evidently kind to all corners; and this other woman will not even show kindness to those who are prompt to secure her comfort.

But at this point I must insert a brief apology. My aim is not to praise one woman to the detriment of others; nor, indeed, do I aspire to tell the story of Jerusalem and all its inhabitants. The range of man’s vision is narrow: shall it comprehend the City of the Holy One, blessed be He? If I speak of the

rabbanit

it is for this reason only, that at the entrance to her house it was again appointed for me to encounter the other old woman.

I bowed and made way for her; but she stood still and greeted me as warmly as one may greet one’s closest relation. Momentarily I was puzzled as to who she might be. Could this be one of the old women I had known in Jerusalem before leaving the country? Yet most of these, if not all, had perished of hunger in the time of the war. Even if one or two survived, I myself was much changed; for I was only a young man when I left Jerusalem, and the years spent abroad had left their mark.

She saw that I was surprised, and smiled, saying: It seems you do not recognize me. Are you not the man who wished to carry my pail on the way to so-and-so’s house?

And you are the woman, said I, who showed me the way. Yet now I stand here bewildered, and seem not to know you.

Again she smiled.—And are you obliged, then, to remember every old woman who lives in the City?

Yet, I said, you recognized me.

She answered: Because the eyes of Jerusalem look out upon all Israel, each man who comes to us is engraved on our heart; thus we never forget him.

It is a cold day, I said; a day of wind and rain; while here I stand, keeping you out of doors.

She answered, with love in her voice: I have seen worse cold than any we have in Jerusalem. As for wind and rain, are we not thankful? For daily we bless God as “He who causes the wind to blow and the rain to fall.” You have done a great

mitzva:

you have put new life into old bones. The stove which you sent to the

rabbanit

is warming her, body and soul.

I hung my head, as a man does who is abashed at hearing his own praise. Perceiving this, she said:

The doing of a

mitzva

need not make a man bashful. Our fathers, it is true, performed so many that it was needless to publicize their deeds. But we, who do less, perform a

mitzva

even by letting the

mitzva

be known: then others will hear, and learn from our deeds what is their duty too. Now, my son, go to the

rabbanit

, and see how much warmth lies in your

mitzva.

I went inside and found the stove lit, and the

rabbanit

seated beside it. Light flickered from the perforated holes, and the room was full of warmth. A scrawny cat lay in her lap, and she was gazing at the stove and talking to the cat, saying to it: It seems that you like this heat more than I do.

I said: I see that the stove burns well and gives off excellent heat. Are you satisfied?

And if I am satisfied, said the

rabbanit

, will that make it smell the less or warm me the more? A stove there was in my old home, that would burn from the last day of

Sukkot

to the first night of

Passover

, and give off heat like the sun in the dog-days of summer, a lasting joy it was, not like these bits of stove which burn for a short while. But nowadays one cannot expect good workmanship. Enough it is if folk make a show of working. Yes, that is what I said to the people of our town when my dear husband, the rabbi, passed away: may he watch over me from the world to come! When they got themselves a new rabbi, I said to them, What can you expect? Do you expect that he will be like your

old

rabbi? Enough it is if he starts no troubles. And so I said to the neighbors just now, when they came to see the stove that my grandson sent me through you. I said to them, This stove is like the times, and these times are like the stove. What did he write you, this grandson? Didn’t write at all? Nor does he write to me, either. No doubt he thinks that by sending me this bit of a stove he has done his duty.

After leaving the

rabbanit

, I said to myself: I too think that by sending her this “bit of a stove” I have done my duty: surely there is no need to visit her again. Yet in the end I returned, and all because of that same gracious old woman; for this was not the last occasion that was appointed for me to see her.