Tudor Queenship: The Reigns of Mary and Elizabeth (4 page)

Read Tudor Queenship: The Reigns of Mary and Elizabeth Online

Authors: Alice Hunt,Anna Whitelock

Tags: #Royalty, #Tudors, #England/Great Britain, #Nonfiction, #Biography & Autobiography

However imaginative, these efforts did not satisfy James’s desire to honor his mother’s memory once he came into his English inheritance. Shortly after his accession he commanded that a memorial be built for Westminster Abbey, to accompany the one that he planned to build for his “dear sister the late Queen Elizabeth.”

7

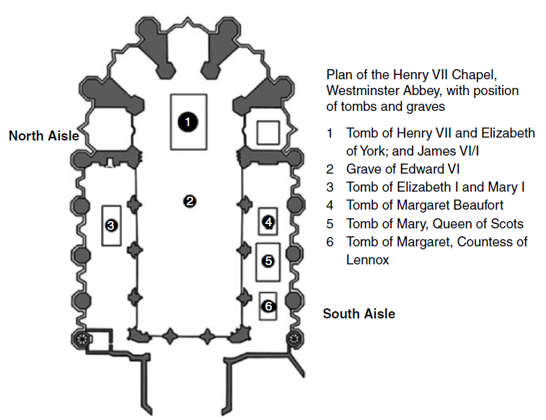

When Mary’s tomb was completed in 1612, she too was disinterred, just as Elizabeth had been in 1606, and, after a second funeral, reinterred in the new tomb. Elizabeth’s and Mary’s memorials were built in a similar style and faced each other across the body of the chapel—Elizabeth’s in the North Aisle, Mary’s in the South. There were, however, significant differences. Mary’s, nearly three times as expensive, was much the grander. Elizabeth’s monument stood alone. Mary’s, in contrast, was flanked by impressive memorials to other mothers of kings. The tomb of Henry VII’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, lay to the east. On its other side stood the memorial erected to Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox, Henry VII’s granddaughter and James’s paternal grandmother, after her death in 1578. Featuring panels inscribed with “recitals of kingly and queenly connections almost unrivalled on any other monument in Westminster Abbey,” the memorial trumpeted James’s descent from the Tudors on his father’s side.

8

The message was reinforced by the statue of Douglas’s son and James’s father, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, kneeling on one side of the tomb. The crown poised over his head announced him as the husband of a queen and father of a king—if not unequivocally a king in his own right.

9

Figure 1.2 Tombs and graves in the Lady Chapel, Westminster Abbey

Thus, from the very beginning of his reign as king of England James envisaged a reconfigured Lady Chapel that would include monuments to two regnant queens: his birth mother, Mary Queen of Scots, and his fictive “mother” Elizabeth I.

10

(We do not know when the decision was taken to include the plaque that referred to Mary Tudor.) These monuments constituted one very public element of the larger project of establishing his unchallengeable legitimacy as the ruler of the restored kingdom of “Great Britain,” now once again an empire. It helps explain his decision to disinter and reinter the two queens, and to erect grand monuments for both—but grander, of course, for his own mother. The tomb politics were a delicate balancing act for many reasons, but by 1612 James’s commemorative project had established a powerful binary opposition between the left and right sides of the chapel, articulated to sterility and fertility respectively.

On the left hand, in the North Aisle, lay Elizabeth, the last of her line, together with Mary, her childless half-sister. “Even as he builds a tomb honouring the Virgin Queen,” writes Walker, “James reminds the public of this historical reality: virgins do not found or further the greatness of dynasties.”

11

In contrast, the right hand side, in the South Aisle, featured a series of tombs of regal women who had fathered kings on both sides of the border. These were dominated by the monument to Mary Queen of Scots, the queen whose personal fertility carried the saga of Tudor dynastic continuity forward to a triumphant new stage in the person of James himself. Very importantly, by displacing Elizabeth from Henry VII’s vault in anticipation of his own burial there, James recaptured the central corridor for a line of kings, not queens. His burial plans placed him at the center of the chapel at the apex of the Tudor dynasty: worthy successor to Henry VII and founder of a new line of British kings.

And Mary Tudor? In 1558 she was buried according to Catholic rites in an unmarked grave on the North Aisle of the Lady Chapel. In her will she had requested that her mother, Catherine of Aragon, be restored to regal dignity by being removed from Peterborough Cathedral and buried with her in Westminster Abbey. She envisaged that in due course “honourable tombs” would be erected to them both, “for a decent memory of us.”

12

But this did not happen, either in Elizabeth’s reign or in James’s. In 1561 the altars in Westminster Abbey were dismantled as part of the drive to suppress superstition that was codified by the 1559 Injunctions. In a supremely ambiguous act, the newly desacralized stones were laid over her grave.

13

The only “memory” that remains is the commemorative plaque at the head of Elizabeth’s monument. As Peter Sherlock notes, it is the only indication that Mary lies under the monument; “indeed, the only record in the entire chapel that Mary Tudor ever existed.”

14

III

Why did Elizabeth fail to memorialize Mary? It is true that in both Edward’s and Elizabeth’s reigns commitment to Protestant reformation unleashed iconoclastic fury against a wide range of “popish remnants,” including tombs. When Elizabeth came to rule over what had become one of the most religiously polarized kingdoms in Europe, it could well be that she and her councilors hesitated, especially in the early years, lest they provoke that fury. But this is not a sufficient explanation. Over the course of the reign the regime devoted considerable effort to protecting existing tombs, royal and noble. They insisted on the distinction between idolatry and due respect for ancient lineage to assert the inherent worthiness of such monuments.

15

It is a measure of their success that by the late 1570s tombs were once again being built in Westminster Abbey. At his wife’s death in 1589, William Cecil, Lord Burghley, zealous Protestant and lynchpin of the Elizabethan regime, articulated what we might regard as the official position. The elaborate funeral ceremonial with which he honored her had no particle in it of the “corrupt abuse” of unreformed religion. It served instead “to testify to the world, what estimation, love and reverence God bears to the stock whereof she did come, both by her father and mother...[w]hich is not done for any vain pomp of the world, but for civil duty towards her body.”

16

He made certain that the evidence of God’s approval would outlast the funeral by commissioning a tomb to be placed in Westminster Abbey. Earlier, in the early 1570s, to similarly honor Elizabeth’s stock, plans were afoot to erect memorials to Elizabeth’s father (buried in St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle) and her half-brother. Although the monuments were never built, the design for Edward VI’s survives in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

17

Such memorials were, for the age, a serious business, especially when they commemorated members of the royal family. When the first Stuart king moved to memorialize his Tudor predecessor, Sir Robert Cecil, Burghley’s son and successor, wrote feelingly of his relief: “It doth my heart good to falsify that blind prophecy, that said none of King Henry VIII’s children should ever be buried, with any memory.”

18

As I have suggested, I think the answer to this conundrum lies in the regime’s determination to enhance Elizabeth’s monarchical legitimacy by undercutting Mary’s. Thus, to understand what happened to Mary in Elizabeth’s reign, we need to recapture why Elizabeth was in a vulnerable position when she inherited the crown, and why and how this contrast with her predecessor was structured. In the eyes of contemporaries, there were three impediments. She was a woman in an age when kingship was gendered male, her legitimacy was problematic, and she was unmarried. In a patriarchal lineage society, these were serious disabilities. In the sermon preached at Mary I’s funeral in 1558, they grounded the Bishop of Winchester John White’s celebration of the late queen’s exceptionality. “She was a king’s daughter, she was a king’s sister, she was a king’s wife,” he marveled. Thus triply sanctioned, Mary became, by birth and breeding, “a queen, and by the same title a king also.” For White and for many others, the formative power of these interpenetrating regalities cancelled out some of the debilities that were deemed to attach to women by nature— debilities that made them ill-suited to rule.

Elizabeth too, the daughter of one Tudor king and sister of another, was, White assured his auditors (who included the new queen), “by the like title and right...both king and queen at this present, of the realm.”

19

But as White well knew, Elizabeth’s status was not as secure as even Mary’s had been. “At this present” Elizabeth was unmarried and hence, for the foreseeable future, sole ruler. It was also the case that her legitimacy was disputable and far more so than Mary’s. In 1536, three years after her birth, Parliament passed the second of the three Succession Acts that punctuated Henry VIII’s reign. This one confirmed the invalidity of his first two marriages, to Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn. It declared that both Mary and Elizabeth were illegitimate and thus barred by law from any right of inheritance, including a place in the succession. True, they were restored to the succession in Henry VIII’s last will in 1543, but this was only on the basis of paternal nomination, not lineal descent.

20

In the early modern period a strong prejudice existed against bastards exercising sovereign power—possibly stronger than that against female rule.

21

According to Henry’s legislation, however, Mary’s illegitimate status was, as it were, venial. It was the fault of the pope, who had taken it upon himself to provide a dispensation for a marriage that was prohibited by God’s law. In contrast, Elizabeth’s misfortune in being born from an invalid marriage was fatally compounded by her having had for her mother a woman of such stark immorality that she was executed for treason. The Act rehearsed Anne Boleyn’s alleged transgressions in minute detail, in terms that made it impossible to avoid the conclusion that Elizabeth was a bastard twice over: illegitimate in the eyes of God (there existed, according to the Act, an unspecified but “just true and lawful impediment”), and, in contrast to Mary, not even her father’s biological child. It was well known that the Lady Anne, “inflamed with pride and carnal desires of her body,” had committed adultery, “confederat[ing] herself” with George Boleyn, “her natural brother,” as well as with four other named individuals. Their “treason” was both proved and very much in the public domain, they having been “attainted...and hav[ing] suffered according to their merits, as by the records...appear[s].”

22

The same allegations circulated at Edward’s death, in order to pave the way for the diversion of the crown to Lady Jane Grey, and they were alluded to, if not explicitly rehearsed, in the legislation that established Mary Tudor on the throne.

23

Indeed, the evidence suggests that Marian regime deliberately sought to underline Elizabeth’s illegitimate status, using arguments that were judged to appeal across the confessional divide. After Mary’s coronation it was proposed that a public declaration of Elizabeth’s illegitimacy be made in parliament. The grounds were to be, not papal sanction, but rather the principal of marital indissolubility that Henry VIII had resoundingly reaffirmed as part of his reformation agenda.

24

“Elizabeth is to be declared a bastard, having been born during the lifetime of Queen Catherine, mother of the queen,” the Spanish ambassador Simon Renard reported. The declaration “will be made without any mention of the Pope or his authority.”

25

(Mary herself clearly preferred the more damning option that presented Anne Boleyn as a strumpet. “As for Elizabeth,” Mary told Renard, “she was a bastard, the offspring of one of whose good fame [he] might have heard, and who had received her punishment.”

26

)

Thus in 1558 the task of legitimating the new queen was not easy. It was complicated by Elizabeth’s identification with the “new religion” and by the very success of one distinctive feature of Mary Tudor’s queenship—her pan-European program. Corinna Streckfuss’s work in this volume clearly shows the powerful appeal of her twin policies of dynastic security, to be effected through a Habsburg marriage, and religious reconciliation with Rome.

27

Historians now generally agree that that program was undone more by gynecological misfortune than by the Protestant bona fides so assiduously credited to the English nation by historians and apologists from John Foxe onward. As Mark Nicholls observes, the situation two years after the marriage, with Mary apparently pregnant and the nation manifestly enthusiastic over the prospect of a Spanish Catholic heir, “presents the observer with a fleeting vision of what might have been.”

28

That vision continued to haunt committed English and Scottish Protestant councilors of state after Mary’s death. It did so in large measure because in its essentials it seemed to live on in the person of another Catholic Mary, the Scottish queen Mary Stuart. Granddaughter of Henry VII, daughter of James V of Scotland, wife of the French king Francis II—and, from 1566, the mother of a son—she became the focal point of a variant Catholic imperial vision, this one centered on French hegemony.

29

Their fears intensified once the 1559 Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis ended the chronic wars between the Habsburg and the Valois dynasties. The new concord raised the specter of Catholic monarchs sinking their differences in order to launch a European crusade against the True Church— and against England, its local habitation. At the same time, the Scottish Mary’s indisputable legitimacy, allied to her Tudor blood, made her, if not, as many thought, the rightful inheritor to Mary Tudor, at least the heir presumptive to the English crown.