True Crime (27 page)

Authors: Max Allan Collins

I turned and saw Nelson swaggering toward us, a big grin riding his face. He scooted in on my side of the booth.

“I made a couple calls,” he said to me. “You’re okay, Lawrence.” He put his hand out. “No hard feelins for the hard time I give you at the house?”

I shook the hand, said, “None.”

“Good.” He looked across at Moran. “I talked to some of your pals in Chicago. I talked to Slim Gray, for one.”

“Alias Russell Gibson. I know him well. And how is Slim?”

“He says Frank Nitti wants you back in Chicago.”

“People in hell want ice water,” Moran said, and gulped the bourbon.

“Maybe you can serve it to ’em,” Nelson said.

“You don’t scare me, little man.”

Nelson smiled at him; the muscle on his jaw was jumping. “That’s fine. Finish your drink—time to go home.”

“I’ll return in my own good time. I have my own transportation.”

“Fine. Drive your own car. But finish your drink, and do it now.”

The blood flowed back into Moran’s face till it was crimson. He half-stood in the booth, leaned forward and waved the glass, the bourbon sloshing around in it, all but shouting as he said, “Don’t threaten

me

, Baby Face. Who do you think you’re crowding? Think I’m afraid of you—or any of that mob?” He stretched his free hand out and held it palm open, cupped. “I have you—all of your crowd—in the hollow of my hand. Right here! In the hollow of my hand.”

Back behind the bar, the plump strawberry blonde looked scared; her father, Kurt, was standing near her, expressionless, but looking our way.

Moran sat back down. “One word from me, Baby Face—and your goose is

cooked

. Understand? Cooked.”

Nelson, jaw muscle throbbing, leaned forward and patted Moran on the arm, soothingly, while the doctor stared into the blackness of the bourbon.

“There, there, Doc,” Nelson said, “don’t talk that way about your pals. We’re on your side. Aren’t we, Jimmy?”

I nodded.

“You’re a great guy, Doc. Just a little tight right now. Now, can you drive back yourself? Or would you like one of us to drive you?”

“I can drive myself.”

“Okay. When you’re ready, come on back to the farmhouse.”

“Well. I’m ready, now.”

“Good. Come along, then.”

“I’ll drive myself.”

“Fine.”

The doctor stood, moved slowly away from the booth. We followed him out onto the street. It was dusk, now.

Nelson smiled at him as we went toward the Auburn. From the sidewalk he called out to us.

“Don’t forget!” Moran said, walking unsteadily, pointing a shaky finger at us. “I know where the bodies are buried. I know where the bodies are buried….”

When we got back just after sundown, everybody (almost) was eating at the kitchen table. The table was covered with an oilcloth, and the oilcloth was covered with bowls of food. Fried chicken. Mashed potatoes. Gravy. Corn on the cob. Cottage cheese. Freshly chopped cabbage. Stacks of white bread. Pitchers of milk; slabs of butter. Biscuits the size of saucers. The smells in the room were warm and good. Around the table sat various public enemies and their molls, chowing down.

“Find a chair!” Ma said to us as we came in. In a calico apron that was too small for her, stocky Ma was milling around, refilling the bowls of food, keeping the chicken frying over at the stove, running the whole damn show. “Get it while it’s hot!” She sounded like a newsie.

Nelson, Moran and I took three of the four empty places at the long table. The remaining place was for Louise, or Lulu as they called her here; she was, I thought, understandably absent.

No one bothered to make introductions, though there were several people at the table I hadn’t seen before. Despite the fact that I’d seen a blue-faced corpse on this table an hour and a half ago or so, I found myself digging right in. I was hungry, the food smelled good, tasted better, and what can I say? Ma Barker was a hell of a cook.

As the meal wore on, I began finding out who the various people were. Quite obviously the lanky man of about forty in coveralls was Verle Gillis, owner of the place, pale blue eyes set in his weathered face like stones; and next to him, a few years younger, a heavyset woman with a sweet face and dark hair in a bun and sad dark eyes was his wife Mildred. Next to Mildred were two boys, one about eight, the other ten or eleven. But for the years between them, they could’ve been twins and had the father’s lanky build and the mother’s almost angelic face—without the sad eyes. The boys were well-behaved; the only talking they did was some whispering back and forth.

“I appreciate your hospitality, Mr. Gillis,” I offered, after a while. I was working on a breast of chicken.

“Our pleasure, Mr. Lawrence. There’ll be no charge for your stay, by the by.”

“Well, that’s very kind.”

“Just remember us to Chicago.”

“Well, uh, sure. Glad to.”

Verle leaned toward his wife and whispered; she nodded, then said, “Mrs. Barker—I want to thank you kindly for preparing dinner.”

“I enjoyed it,” Ma said. She was finally sitting down and eating, starting her first plate when most of us were on our second or third. Doc Moran, however, seemed morose and was picking at his first.

Ma went on: “I apologize for taking over your kitchen like I done while you was gone. I just figured it was gettin’ late and I should start ’er up.”

Mildred said she was “happy” Ma had taken over; but I didn’t think Mildred meant it.

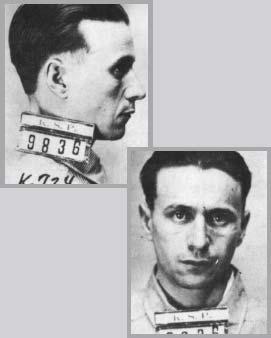

F

RED

B

ARKER

Ma did, however, saying, “Well, I hope you’ll let me pitch in again while I’m here. I just love cookin’ for my boys.”

Fred, sitting to one side of her (she was at the head of the table, of course), spoke through a mouthful of potatoes; what he seemed to say was, “Nice to have your good home cookin’ again, Ma.” Or something.

One by one everybody complimented Ma, and meant it—hurting Mildred’s feelings, I thought—though Fred’s girl Paula seemed to like the glass of liquor she had brought to the table more than the meal.

In the brightly lit kitchen I noticed for the first time just how hard the faces of the women were. These women—all of them naturally attractive, and well-groomed, if occasionally overly made up—were in their early twenties; but they had a hard, worn look that made them seem ten years older. But it was an oldness age didn’t have anything to do with. A sixteen-year-old prostitute is old that way.

With the exception of Helen Nelson: She had a smooth, young face. Worry seemed never to have crossed her consciousness.

She and her husband flirted, giggling with each other, throughout the meal. It was as though they were newlyweds. Later I learned they had two kids and had been married for years.

Down at the other end of the table, opposite Ma, was a slight man in glasses with his hair combed back, with a tight mouth and gray, dead eyes. I’d been in the room fifteen minutes before he introduced himself, suddenly.

“I’m Karpis,” he said.

I’d guessed that.

“The folks around here call me Old Creepy,” he said. “I don’t know why.” And he smiled. It was a ghostly, ghastly smile. It was a smile a mean kid wore when pulling the wings off a bug. He was pulling part of the wing of a chicken off, at the moment.

“Or O.C.,” Nelson corrected.

“Or O.C.,” Karpis allowed. “I’ll answer to that.”

I nodded to him. “Glad to meet you, Karpis.”

He held up a greasy hand. “We can shake hands later. I understand your name is Lawrence.”

“That’s right.”

“From Chicago.”

“As of now.”

“And connected.”

“Well, yeah.”

“I’ve had dealings with the Chicago Boys before.”

“Really.”

“I’m not crazy about Chicago. A plain Kansas boy like me, I prefer the wide-open spaces. I like to be able to make a getaway through a field or a farmyard, down a dirt road, across a dry creek bed. In Chicago, the city—it’s all asphalt and traffic and big buildings. Who needs it.”

I swallowed a bite of mashed potatoes and gravy. “It’s nice out here. I could be a convert to this country life.”

Karpis nodded; the glasses and slicked-back hair made him look like a math teacher. But that smile would give Lon Chaney the willies.

He said, “You’ll find the company better, too, I think. We work for a living, unlike your hoodlum pals.”

He returned to eating his chicken. I didn’t understand what he meant, but I didn’t feel like following up on it.

Ma said, “Somebody ought to go up and drag that girl down here. She needs to eat.”

She meant Louise.

Dolores, sitting next to her man Karpis, said, “I don’t think so, Ma. She’s had quite a shock. She’s crying her fool head off. I don’t think she could keep anything down.”

Ma shook her head, looking at the remaining food on the table. “It’d be criminal to waste this good food,” she said. “The poor little thing ought to come down and eat.”

Paula smiled as some whiskey went smoothly down, then said, “Maybe I could take a plate up to her.”

Ma was adamant. “She should get right back in the swing of things. Best thing in the world for her.”

I couldn’t help myself. I said, “Ma, don’t you think it’s asking a little much of her to sit down and eat at the table she just saw her boyfriend stretched out dead on?”

That should have killed a few appetites, but everybody’s appetite was alive and well at this table—except for Moran, who was looking at Paula’s glass with glum envy.

Ma didn’t get my point. She said, “It’s just a table.”

Doc Barker, who’d been silently (and dedicatedly) eating, lowered his ear of corn and smiled messily and said, “Ma, sometimes you’re a riot.”

“Don’t sass!”

Across the table from his brother, Fred grinned his mostly gold grin, and said, “You’re a cold-blooded old Ozark gal, Ma, no gettin’ around it!”

“Well,” Ma said, her feelings a little hurt, “there’s apple pie for them that wants it.”

Everybody wanted it except Moran, who sat at the table, slumped. Paula finally took pity on him and went out in the other room to get her pint; she filled a water glass half full for Moran, and freshened her own glass, too.

But he drank it quickly down, and most of us were hardly started on our pie when he stood and announced, “And so to bed.”

Ma said, “So early, Doctor?”

He touched a hand to his chest with mock-drama. “I’ve had a long, tiring and quite difficult day, madam. I lost a patient, in this very room, mere hours ago. There are times when I seek refuge in a bottle; but there are times when sleep can serve that function just as well.”

The two farm boys nudged each other with elbows and laughed. The old doc talked funny.

“Sit down, Doc,” Nelson said, quietly, cutting a small bite of pie with his fork.

“Are you addressing me…Baby Face?”

A pall fell over the room.

Nelson smiled as he forked the bite of pie; lifted fork to lips, ate. “Yes. Sit down.”

“I’m tired. And I will take no orders from—”

“Sit down.”

There’d been no menace in Nelson’s voice.

But Moran thought it best to sit down.

Saying, “Why is my presence required here?”

Nelson said, “Ain’t good manners not to clean up after yourself.”

Moran seemed puzzled, glanced at the area near his plate where he’d been sitting, which was rather tidy actually.

Like a stage magician, Nelson made a sweeping gesture with one hand that summoned to my mind’s eye, and I’d wager to that of anyone else who’d been in this room not long ago, the blue-faced corpse that had been stretched out on this very table.

Finally my appetite deserted me. I pushed the plate of pie away and suddenly the food in my stomach was churning.

“He’s still in the barn,” Nelson said. He looked at Fred. “Right? You haven’t moved him?”

The youngest farm boy whispered to his mother, “Who?” and she shushed him.

Fred said, “He’s out there. Not going anywhere.”

“Well,” Nelson said, rising, wiping his hands with a napkin, “it’s time he did.”

Moran was wide-eyed, indignant, but a little afraid. “This is preposterous.”

Doc Barker rose. “I agree. You botched the operation, Doc. Least you can do is help dispose of the remains. Besides—like you always like to tell us—you know where the bodies are buried. Why should this time be any different?”

Soon five of us were moving through the darkness. Six, counting the sheet-wrapped body of Candy Walker. Doc and Fred Barker carried him, one at either end of him, and he sagged in the middle. Nelson, who knew his way around the farm (I was beginning to gather that he really was related to Verle and Mildred), led the way, with a flashlight in hand. The flashlight was hardly necessary: it was a clear night, stars scattered across the sky like diamonds across a dark tapestry (stolen diamonds, in this company) and part of the moon was up there, working for us, too. The night air was almost cool and the smell of grass and wheat and such was strange and strangely soothing to these city nostrils. I had the shovels over my shoulder, three of them. Moran, muttering to himself, was carrying a heavy bag of quicklime.