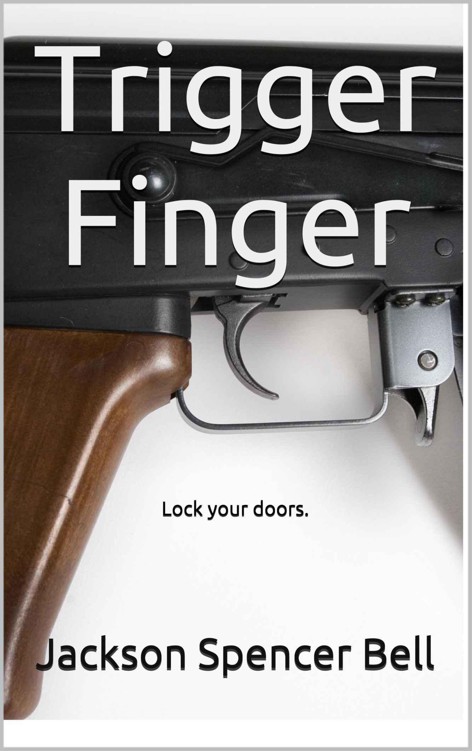

Trigger Finger

Authors: Jackson Spencer Bell

For Angel

1.

The typical

nightmare ends with the victim shooting bolt-upright in bed and trying to

orient himself to his surroundings as the dream he just escaped melts

away.

Mine didn’t end that like that.

I woke up but didn’t sit up;

au contraire

, I awoke in a prone

position and stayed that way, hollering at the top of my lungs, panicked but

motionless.

Whatever had happened in my

dream, I took it lying down.

So while I

may have been less than a lion in real life, in my nightmares I was a complete

pussy.

“Kevin!

Wake up!”

Allie, my

wife.

She shook me vigorously, either

trying to shake me awake or shake me to death so I would shut the hell up.

I opened my eyes and quickly catalogued

everything around me.

My bedroom, my

senses said.

A hand on my shoulder, not

a claw.

My wife, not the enemy.

My house.

I’d had a bad dream.

Nothing to

see here, nothing to look at, all’s well, sorry for the interruption, carry

on.

I stopped

yelling.

I lay still for a moment and

stared into the master bathroom before flipping over and pressing my face into

Allie’s chest.

Her warm skin smelled

like lavender.

She held me as my heart

rate returned to normal and confusion and terror yielded to understanding and

shame.

“Sorry,” I

mumbled.

“It’s okay,” she

said.

Silence.

Then:

“What was it

about?”

“You know,” I

replied.

I let her hold me

for a long time, because it felt good and she smelled good and I needed

pleasant things just then.

She made it

easier to resist the urge to remember my dream.

My mind likes to pick at scabs.

Left to its own devices, it wouldn’t rest until it made me unhappy

again.

“I think you need

to see somebody,” she said.

“I’m just nervous

about doing the show,” I replied, still talking to her chest.

I intended to keep my face there until she

forcibly evicted me.

“Stage fright.

It’ll pass.”

“This is more than

stage fright.” She pushed me back so she could look at me.

My recent behavior had dug deep lines of

concern into her face.

“You need help.”

“I need to drink

more and work less.”

“You should go see

Tom’s friend, the psychologist.

You

shouldn’t have to go through this.”

“I don’t need a

shrink,” I said, pulling away.

“Okay, Kevin,

I

need for you to see Tom’s psychologist

friend.

I

shouldn’t have to go through this.”

Tom Spicer, the

Spicer in Carwood, Allison, Spicer and York, P.A., held a certain amount of

influence over me.

I had practiced with

the firm for ten good years.

Maybe not

so good the last six months, but the nine and a half years before those had

earned me enough brownie points that my personality issues resulted in a

cautious referral to a shrink instead of a Go Work Somewhere Else meeting with

the equity partners.

Tom had given me a

business card and said:

Talk to this guy

right here.

You can trust him.

He had given me

the card two days ago.

I hadn’t called

the number on it yet.

“I don’t like

seeing you like this,” she said.

“It’s

not right.”

I snuggled back up

to her.

“I can handle it,” I said into

her chest.

“But I can’t.

I need this to be over.

We

need this to be over.

And it can’t be

over until this stops.

Not really.”

I inhaled her

scent.

The nightmare seemed far away

now, the mindless terror a distant memory.

My heart rate fell.

I remembered

Abby as a tiny baby, how Allie would hold her just like she was holding me and

how she would first stop fussing, then stop moving and then fall totally

asleep.

Maybe it was the smoothness of

her skin or the steady heartbeat beneath it; either way, Allie’s presence

reached a place inside me that nothing else could, an elemental control panel

where she could slow my heart or speed it up at will.

She kissed the

crown of my head.

“You’re still my

hero, you know,” she murmured.

“Getting

help isn’t going to change that.”

I was falling

asleep now.

“Mmmhmm.”

“You won.

You did it.

Now it’s time to clean everything up, okay?”

“Mmhmm.”

“So you’ll call

that number in the morning?”

“First thing,” I

mumbled.

She continued to

hold me until I fell out of the world again.

This time, I had no nightmares.

2.

In early February

of this year, I shot and killed two men in my home.

I call them “men” only because I understand

that I’m supposed to do that.

They had

two arms and two legs and walked upright and had opposable thumbs; everybody

else called them men.

Me?

I didn’t think two arms and two legs made

somebody a man any more than the absence of a carapace and antennae made him

not

a cockroach.

“Quit calling them

‘roaches,’ okay?”

Craig Montero, who had

become my coworker, then my friend and finally my attorney, had advised me of

this before I ever talked to the press.

“No ‘vermin,’ either, or ‘rats’ or ‘snakes’ or anything like that.

You’re an innocent homeowner forced to defend

his castle and his family.

You didn’t

want to kill these guys; you had to.

You

are deeply saddened and traumatized by what these

men

forced you to do.

Your

sympathy goes out to their families.”

“I am deeply

saddened and traumatized by what these men forced me to do,” I repeated in his

office, a carbon copy of my own.

“My

sympathy goes out to their families.”

“Don’t grin when

you say it.”

“Okay.”

“That’s fucked

up.

It makes

you

look fucked up.”

“Okay.”

“Heroes don’t

gloat.”

“Okay.”

“Dangerous

psychopaths gloat.

You’re not a

dangerous psychopath.”

“Okay,” I said yet

again.

And so I called

them “men” to the outside world even though I didn’t believe they

qualified.

They entered my home through

an unlocked door in my basement and found me asleep on my man-cave couch in

front of the Carolina-Virginia Tech basketball game.

They used my own softball bat to crack me

over the head in an attempt to kill me, then proceeded upstairs with a little

bag of goodies that included handcuffs, duct tape, rope, a knife, pretty much

anything that might be useful to you and a buddy if you’re looking to rape a

woman and her thirteen-year-old daughter.

But, contrary to the greater weight of the evidence—

see

Nazi Germany vs. Humanity

, (1933-1945),

The Rwandan

Genocide vs. Humanity

, (1994)—God existed.

He placed His hand between that bat and my skull.

I regained consciousness a few moments later,

woozy and terrified but otherwise okay.

I whipped my AK-47 out of my gun safe—tucked away in my man-cave—and

charged up to the ground floor, where I shot them both.

They never even found the stairs.

Anyway, I became a

killer that night out of necessity, and that sucked because I respected

life.

A divorce lawyer by trade, I had

never

intentionally

whacked anything

higher than a wasp.

In my mid-twenties,

I accidentally ran over a box turtle on one of the myriad back roads that

crisscross southern Alamance County,

North Carolina, and the

experience left me so riddled with guilt that I actually had to pull over and

do some deep breathing to deal with it.

I sat in my car on the side of the road and thought about how if I

hadn’t been screwing around with my CD player, I’d have seen the turtle and

could have avoided it.

I felt terrible

about it then—it sucks to kill anything, but it really sucks to kill something

cute—and I continued to feel bad about it long afterwards.

So much so that whenever I see a turtle

trying to cross the road now, I pull over and help.

But I never

experienced a shred of remorse for shooting the two dildos that broke into my

home.

You’d think that a civilized man,

an educated man, a family man like me would have felt

something

at having taken human life, no matter the necessity.

I’d seen documentaries where veterans of

various wars teared up in front of the camera over bayoneting this Nazi or

napalming that North Vietnamese, pick your former enemy.

These people had trained for it, yet they

cried on camera.

They needed counseling.

I had to have

Craig Montero tell me not to grin.

My brother Bobby

had an explanation for this.

“You’re a hard son

of a bitch,” he said to me over beers one time in the wake of the

shooting.

A Marine and a veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan, Bobby was a logical

choice for me to consult regarding my feelings about taking lives.

“I never thought I’d say that, but there you

go.

You’re a hard son of a bitch.”

I appreciated

that, because Bobby was a hard son of a bitch himself.

And now, instead of calling me a

chairborne commando

, a

REMF

(Rear-Echelon Mother Fucker) or

something more prosaic—like

pencil-pushing

pussy

—my brother called me a

hard son

of a bitch

.

I liked that.

“And because

you’re a hard son of a bitch, you don’t give a rat’s ass about these two

guys.

And think about it, dog; what were

these guys going to do to Allie and Abby?”

Dog

, instead of

man

or

dude

.

Another thing hard sons of bitches called other

men.

“Seriously, duct

tape and handcuffs?

After I found that

shit out, I’d have gone back over and killed them again.

Fuck them.

And fuck anybody who thinks you should feel bad about it—including

you.

Listen, did you rip yourself up that time you killed the copperhead in

the garage?”

There—I

had

intentionally killed.

Five years ago, Abby found a poisonous snake

coiled up beside her little pink bicycle in our garage, and I cut its head off

with a shovel.

“No,” I admitted.

But at the same

time, I didn’t say to Bobby then, I hadn’t felt

proud

of it, either.

There

existed now a dark truth I hadn’t related to anybody; when I thought about

pulling that trigger I felt not sorrow, remorse or disgust but

pride.

I sat in court, in my car, on the john and thought,

I’m awesome

.

With the

twitching of my trigger finger, I cleansed mankind.

I excised two bits of gangrene from the flesh

of my species.

A mediocre father,

husband and lawyer, I finally did something not only extraordinary, not only

courageous but

good

.

I made society a better place.

Whether that made me a psycho or not, that

was how I felt.

I wanted a parade.

So when I finally

walked into Dr. Robert Koenig’s office for the first time, I actually didn’t go

in there to discuss my feelings, to analyze my healing, to share my pain or

anything like that; I went to brag.

And

to maybe figure out why, when I felt nothing but pride over this, it still gave

me nightmares.

“So,” said Dr.

Koenig, “are you a gun enthusiast.”

Despite the

diplomas on the wall that marked him as a graduate of Emory University and the

University of Georgia, he asked the question in that instantly recognizable way

peculiar to those from Pennsylvania—the up-and-down of the sentence, the

absence of the expected interrogatory rise at the end.

Echoes, perhaps, of the German immigrants who

had settled the area where he grew up.

I

smiled at the inflection.

Allie had talked

like that once, as a freshman in college there at the beginning of the years in

North Carolina

that would gradually eradicate her Yankee accent.

When she got drunk or spent too much time

around her family, it would come out again.

Did you like the pot roast.

Did you run into a lot of traffic there on

95.

Are you a gun enthusiast.

I answered, “I am

now.”

A battered issue

of

Southern Rifleman,

the monthly

gospel of gun nuts everywhere,

rested

in my hands.

The magazine exerted a

calming effect on me; consequently, I hadn’t let go of it since coming in.

This probably made me look crazy here, which

was totally not my desired effect.

My

dark hair, thinning but still there, poked this way and that in a fashionable

mess that required a dab of gel and almost a whole minute of teasing to

perfect.

The suit I had worn today

remained hung on a body from which all unnecessary fat had melted over the

preceding months.

I had always been

handsome—hey, man, I can’t lie—and at thirty-six, the weight loss only enhanced

this.

I looked good, I thought.

Felt good, too.

Not at all like a man who should clutch a gun

magazine like some kind of redneck security blanket.

I forced myself to

lay it in my lap.

The coffee table that

stood between the Doc and I looked like a beaten refugee from a fraternity

house.

Scratches, cigarette burns and

drink rings marred a cheap veneer surface that ruined the chord of understated

luxury prevailing throughout the rest of the office.

The suede couch and chair and the mahogany

desk could have come from a showroom in New York

or London.

The conference table looked like

Craftique.

And among all this, here at

my knees sat the furniture droppings of a passing Wal-Mart.

I didn’t want my precious magazine—the trophy

I had received for my good deeds—on that damn thing.

The separation of

hand and

Southern Rifleman

lasted

exactly two seconds, and then I picked it up again.

I cleared my throat.

“Umm…I’m not a

subscriber.

Somebody told me about this,

so I went to Barnes & Noble and got one.

I thought maybe it’d be a good thing to show you.”

“Can I see it?”

He tacked a

question mark to the end of that one.

I

looked down at my magazine for a moment, then forced myself to hand it over.

“What am I looking

for?”

“Turn to the

back.

There’s this section called Heroes

of the Month, where they do these write-ups of everybody who bagged a home

invader since the last issue.

Back

page.

Mine’s the first paragraph.”

He opened the

magazine.

The pages sounded like dry

leaves as he turned them.

He was a thin

man, a marathon runner by appearance, with fingers almost as long and skinny as

his legs.

He wore jeans and a navy-blue

turtleneck sweater.

The narrow face and

bald head perched atop the shoulders recalled Steve Jobs, the departed icon of

Apple fame.

He even wore little rimless

glasses like Jobs and sported the same carefully-cultivated beard stubble.

They could have been twins.

He located the

story and adjusted the glasses on the bridge of his prominent nose.

I waited as he read.

When he finished, he closed the magazine and

handed it back to me.

I gripped it in

both hands again.

Realizing how crazy I

looked then, I blushed and forced myself to set it down.

“See, Doc, I’m not

just a Hero of the Month,” I said.

“I’m

a

double

Hero of the Month.

That’s what it says.

Listen, before I came in here, had you ever

heard of me?”

He nodded.

“Thought so.

Everybody in Burlington knows who I am now, because I’m a

double Hero of the Month.

I’m Kevin

Swanson.

I’m a bad son of a bitch, I’m a

hard

son of a bitch, I deserve a

frigging medal.

I’m on top of the

world.

My teenage daughter thinks I’m

cool again, and my wife respects me as a man again.

I have 1500 Facebook friends, up from 95 in

January.

I can tell you with complete

sincerity that my life has never been better.

Never.

That’s God’s honest

truth.

Yet here I am in a shrink’s

office.

Talking to you.”

He regarded me

silently, a skinny finger over his skinny lips.

He appeared deep in thought, as a psychologist in session should

appear—although, I realized, he could have been thinking about anything.

An upcoming oil change on the Mercedes,

perhaps, or whether he should get kale or spinach to go with the organic

free-range chicken tonight.

He looked

like an intelligent man, an intellectual man, but I learned a long time ago

that some people just looked thoughtful.