Travels into the Interior of Africa (28 page)

Read Travels into the Interior of Africa Online

Authors: Mungo Park,Anthony Sattin

Park spent the summer of 1798 at home in Foulshiels on the Scottish borders, but on 9 September was at the Home Office in London. The meeting appeared to have been successful – the government certainly had the impression that the explorer would be heading to Australia for them. But Park soon informed his patron that he would not be sailing south. Banks was furious. ‘Till your absence from London,’ he wrote, ‘you always appeared to solicit [the appointment] with eagerness’ Park complained that the fee he was being offered did not match his status, but Dickson, his brother-in-law, suggested otherwise: ‘I have found out from his sister, which is my wife,’ he wrote to Banks from Covent Garden, ‘that there is some private connection, a love affair in Scotland, but no money in it (what a pity it is men should be such fools that might be of use to their country); that is the cause of it.’ A love affair indeed! During the summer of 1798, Park had fallen for Alison Anderson, the daughter of his former master. But Alison was in Scotland and Park was in England, with a book to write.

Once again, Bryan Edwards offered to edit the traveller’s pages, though neither men seemed to enjoy the task at first: Edwards’ letters to Banks during this time are full of complaints at Park’s lack of talent and application, ‘the occurrences which he relates are so unimportant, that it requires some skill in composition and arrangement.’ It wasn’t until November 1798 that Park hit his stride and Edwards began to relax, describing Park’s account of his captivity in Ludamar as ‘extremely well done’. By the end of January, the conversion was complete and Edwards was full of praise: ‘Park goes on triumphantly,’ he wrote to Banks. ‘He improves in his style so much by practice that his journal now requires but little correction; and some parts, which he has lately sent me, are equal to anything in the English Language.’

Park’s audience seemed to share Edwards’ opinion.

Travels into the Interior of Africa

was published in April 1799. The entire first run of around fifteen hundred copies sold in a week and two further editions sold out that first year. The critics liked it too, with the

Gentleman’s Magazine

setting the tone by claiming that ‘Few books of Voyages and Travels have been more favourably received.’ The success of Park’s

Travels

ensured a full house for the African Association’s general meeting on Saturday 25 May 1799. Edwards was expected to outline the Association’s progress to members, while Banks, as Treasurer, would give a financial report. But Edwards was too ill to attend the meeting and Banks spoke in his place. The world had been transformed in the eleven years of the Association’s existence and the French, who were now in control of much of Europe, had clear designs on Africa, as they had shown by invading Egypt the previous year, though Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile had forced Napoleon to scale down his ambitions. Here, if ever, was a moment for Banks to beat the Association’s drum and he wasted no time in doing just that.

Banks began by praising Park’s many remarkable qualities, his ‘strength to make exertions, constitution to endure fatigue and temper to bear insults with patience, courage to undertake hazardous enterprises when practicable, and judgment to set limits to his adventure.’ Then he turned to the significance of Park’s discovery. ‘We have already by Mr. Park’s means opened a Gate into the Interior of Africa, into which it is easy for every Nation to enter and to extend its commerce and discovery from the West to the Eastern side of that immense continent.’ It was but a short journey from the Gambia to the Niger rivers and British trade could easily take control of central Africa’s markets, once the British government had smoothed the way: ‘A detachment of 500 chosen troops would soon make that Road easy, and would Build Embarkations upon the Joliba [Niger] – if 200 of these were to embark with Field pieces they would be able to overcome the whole Forces which Africa could bring against them.’

With the book launched and the meeting over, Park went north. With both his reputation and his finances enhanced he now decided it was time to ensure his posterity in another way: in Scotland he married Alison and settled down to life in the country. The only cloud on his horizon was his inability to find work as a surgeon.

Without any appropriate work, once the scars from his African journey had healed, the fevers had eased, the stories been told and retold, Park began to long for new adventures. In July of 1800 he heard that British forces had recaptured the Ile de Gorée, off the Senegalese coast, and wrote to Banks pointing out its possible significance in developing trade with the African interior. In 1801, there was renewed talk of an expedition to New South Wales. In the spring of that year, the doctor was in London to discuss the proposal with Banks. On 12 March he wrote a letter home, which reveals much of his mood at the time:

My lovely Ailie, nothing gives me more pleasure than to write to you, and the reason why I delayed a day last time was to get some money to send to you. You say you are wishing to spend a note upon yourself. My sweet Ailie, you may be sure I approve of it. What is mine is yours, and I receive much pleasure from your goodness in consulting me about such a trifle. I wish I had thousands to give you, but I know that my Ailie will be contented with what we have, and we shall live in the hope of seeing better days … I am happy to know you will go to New South Wales with me, my sweet wife. You are everything that I could desire; and wherever we go, you may be sure of one thing, that I shall always love you.

Nothing came of the Australian project, but in the meantime there were changes at home: at the end of 1801, Park, his wife and child made the short move to Peebles to take up a medical practice. It seems he was as energetic as a local doctor as he had been as a traveller. The practice provided only a meagre living, but there were the consolations of home, the countryside and of some inspired company, including that of the novelist Sir Walter Scott. But Park was restless, could not forget Africa and, around this time, told Scott he ‘would rather brave Africa and all its horrors than wear out his life in long and toilsome rides over cold and lonely heaths and gloomy hills.’ Alongside the desire to get back to Africa, there was also a motive: he had guessed the Niger’s source and settled the question of its direction, but the matter of its termination and of Timbuktu had still to be resolved. He felt that he should be the one to answer the outstanding questions about the Niger. In October 1803, there was also the calling: a letter arrived summoning him to the Colonial Office in London.

The plan proposed by Lord Hobart of the Colonial Office was not what Park had been expecting. Instead of being sent on a geographical mission to search for the end of the Niger, he was asked to conduct negotiations on trade treaties with the various rulers and also to build a string of forts between the Gambia and Niger rivers. To make all this possible, he was to be accompanied by a gunboat and a small force of British redcoats.

A change in administration in London put the plan on hold – it took most of 1804 for the new ministry of Prime Minister Pitt to establish itself. During this time, Park returned to Scotland. With him travelled a Moor by the name of Sidi Omback Boubi, a government-sponsored Arabic tutor, who must have caused quite a stir in Scotland by abstaining from drinking alcohol and by his habit of slaughtering his own food. By the autumn of 1804, the new Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Camden, had had time to consider the project. Camden was unenthusiastic about the military objectives. Instead, he wanted ‘a Journey of Enquiry without any military attendance upon it’, paid for by the government, but organised by the African Association.

Major Rennell, the Association’s geographer, had studied the

information

brought back by Park, sent by Houghton and gleaned from the Moors in London and concluded that ‘it can scarcely be doubted that the Joliba or Niger terminates in lakes in the eastern quarter of Africa.’ Park arrived in London insisting that the Niger would be found to flow into the Congo and from there into the Atlantic. To prove it, he suggested taking thirty soldiers and six carpenters, crossing from the Gambia to the Niger, building boats and sailing to the end of the river. Rennell was convinced Park would end up stranded in the middle of nowhere. Banks agreed with Rennell that it was ‘one of the most hazardous [expeditions] a man can undertake’, fraught with ‘the most frightful hazards’, but still believed Park should go.

On 18 December, 1804, in the comfort of the Ministry in London, Banks and Lord Camden agreed a timetable: if Park left England in January, he would need two months to reach the uppermost navigable part of the Gambia, two months to cross to the Niger and two months to build his boats. Timing was crucial: they needed to reach the Niger before the rains started, before malaria became a problem, paths were made slippery, rivers swollen.

Neither Banks nor Park had counted on the slow grinding of

governmental

bureaucracy: it took a month for Park’s instructions to be written out, even though they were more or less copied from his original proposal. With a captain’s commission, a credit of £5000, a guarantee of a settlement of £4000 for his wife in the event of his death, Park sailed out of Portsmouth on 31 January, accompanied by his brother-in-law

Alexander

Anderson, and a Selkirk artist, George Scott. Among his papers was a letter from Lord Camden reminding him that ‘His Majesty has selected you to discover and ascertain whether any, and what commercial intercourse can be opened, with the interior’.

By March they were on Cape Verde Island and by the beginning of April, Park was able to write to Ailie from Ile de Gorée assuring her that everything was now ready. There had been no problem raising

volunteers

. On the contrary: ‘Almost every soldier in the garrison volunteered to go with me.’ Park had chosen only the best. ‘So lightly do the people here think of the danger attending the undertaking, that I have been under the necessity of refusing several military and naval officers who volunteered to accompany me.’ He then ended, ‘The hopes of spending the remainder of my life with my wife and children will make everything seem easy; and you may be sure I will not rashly risk my life, when I know that your happiness, and the welfare of my young ones, depend so much upon it.’

Park and his party of forty-three Europeans did not reach Pisania, at the end of the navigable stretch of the Gambia River, until the last days of April, when, according to Banks’ timetable, they should already have been building boats on the Niger. May is one of the hottest months in West Africa, with the weather becoming increasingly oppressive until the rains break in June. Park didn’t mention this in his letters home, but he was well aware of the problem, as the first entry in his journal shows. Nor could he have failed to remember what he had written of Karfa Taura, the slave trader who had saved him on his journey from the Niger back to the coast: ‘when a caravan of natives could not travel through the country, it was idle for a single white man to attempt it.’

He knew the difficulties ahead and could have called a halt and sat out the heat and the rains on the Gambian coast or at the fort on Gorée. But there had been enough delays. He was Mungo Park, the celebrity traveller who had gone into the interior and lived to tell the tale. And this time he was not alone, but travelling with a caravan of white men.

A

NTHONY

S

ATTIN

London

2003

BOOK TWO

The journal of a mission to the interior of Africa in the year 1805

(Chapters 1–5 are Park’s journal almost verbatim, only astronomical observations, lists of stores, etc, being omitted. The style, as might be expected in a simple log written up

en route,

is not so polished as in Book One; indeed it is surprising, considering the difficulties which beset him, that Park was able to keep a journal at all.)

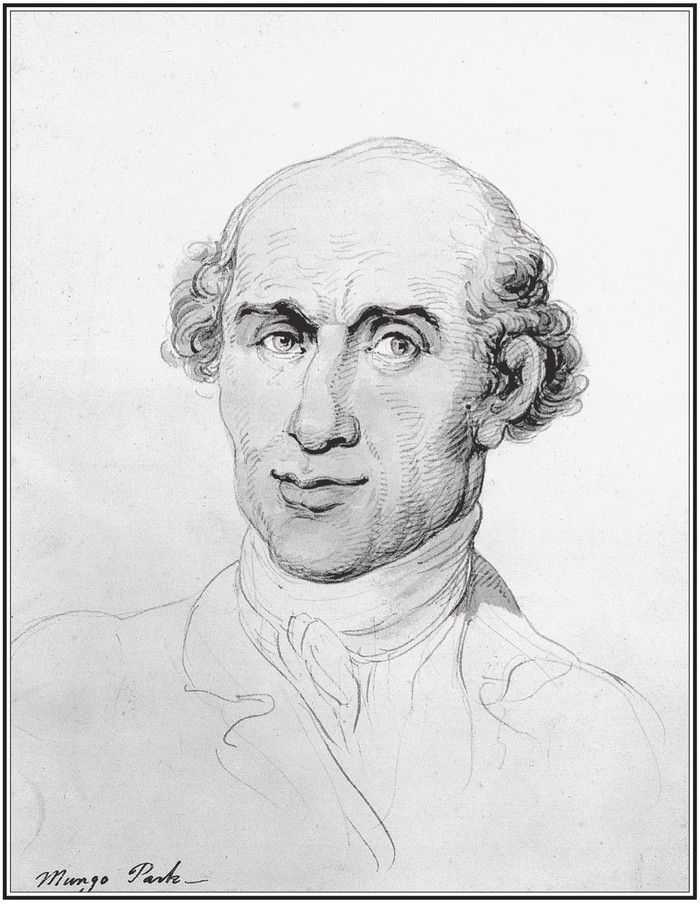

Mungo Park by Thomas Rowlandson c. 1805 by courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

Departure from Kayee – Arrival at Pisania – Preparations there, and departure into the Interior – Samee – Payment to Mumbo Jumbo – Reach Jindey – Departure from Jindey – Cross the Wallia Creek – Kootakunda – Madina – Tabajang – Kingdom of Jamberoo – Visit from the king’s son – Tatticonda – Visit from the son of the former king of Woolli – Reach Madina, the capital of Woolli – Audience of the king; his unfriendly conduct – Presents made to him and his courtiers – Barraconda – Bambakoo – Kanipe; inhospitable conduct of its inhabitants – Kussai – Nitta trees; restrictions relating to them – Enter the Simbani woods; precautions thereon, and sacrifice and prayers for success – Banks of the Gambia – Crocodiles and hippopotami – Reach Faraba – Loss of one of the soldiers – Rivers Neaulico and Nerico.

A

PRIL 27TH

,

1805

‒ At ten o’clock in the morning took our departure from Kayee. The

Crescent,

the

Washington

, and Mr Ainsley’s vessel did us the honour to fire a salute at our departure. The day proved remarkably hot; and some of the asses, being unaccustomed to carry loads, made our march very fatiguing and troublesome. Three of them stuck fast in a muddy rice-field about two miles east of Kayee; and while we were employed in getting them out, our guide and the people in front had gone on so far that we lost sight of them. In a short time we overtook about a dozen soldiers and their asses, who had likewise fallen behind, and being afraid of losing their way, had halted till we came up. We in the rear took the road to Jonkakonda, which place we reached at one o’clock; but not finding Lieutenant Martyn nor any of the men who were in front, concluded they had gone by New Jermy, etc, therefore hired a guide and continued our march. Halted a few minutes under a large tree at the village of Lamain-Cotto, to allow the soldiers to cool themselves; and then proceeded towards Lamain, at which place we arrived at four o’clock. The people were extremely fatigued, having travelled all day under a vertical sun, and without a breath of wind. Lieutenant Martyn and the rest of our party arrived at half-past five, having taken the road by New Jermy.

April 28th

– Set out for Pisania. We passed two small Foulah towns and the village of Collin, and reached the banks of the Gambia at half-past eleven o’clock. Halted and gave our cattle water and grass; we likewise cooked our dinners, and rested till three o’clock, when we set forward and arrived at Pisania at sunset. Here we were accommodated at Mr Ainsley’s house; and as his schooner had not yet arrived with our baggage, I purchased some corn for our cattle, and spoke for a bullock for the soldiers.

April 29th

– Went and paid my respects to Seniora Camilla, who was much surprised to see me again attempting a journey into the interior of the country.

April 30th

– Mr Ainsley’s schooner arrived, and we immediately began to land the baggage and rice.

April 31st

– Gave out the ass saddles to be stuffed with grass, and set about weighing the bundles. Found that after all reductions, our asses could not possibly carry our baggage. Purchased five more with Mr Ainsley’s assistance.

May 1st

– Tying up the bundles and marking them.

May 2nd

– Purchased three asses, and a bullock for the people.

May 3rd

– Finished packing the loads, and got everything ready for our journey.

May 4th

– Left Pisania at half-past nine o’clock. The mode of marching was adjusted as follows. The asses and loads being all marked and numbered with red paint, a certain number of each was allotted to each of the six messes, into which the soldiers were divided; and the asses were further subdivided amongst the individuals of each mess, so that every man could tell at first sight the ass and load which belonged to him. The asses were also numbered with large figures, to prevent the natives from stealing them, as they could neither wash nor clip it off without being discovered. Mr George Scott and one of Isaaco’s people generally went in front, Lieutenant Martyn in the centre, and Mr Anderson and myself in the rear. We were forced to leave at Pisania about five hundredweights of rice, not having a sufficient number of asses to carry it. We were escorted till we passed Tendicunda by Mr Ainsley and the good old Seniora Camilla and most of the respectable natives in the vicinity. Our march was most fatiguing. Many of the asses being rather overloaded, lay down on the road; others kicked off their bundles, so that, after using every exertion to get forward, we with difficulty reached Samee, a distance of about eight miles. We unloaded our asses under a large Tabba tree at some distance from the town, and in the evening I went with Isaaco to pay my respects to the Slatee of Samee.

May 5th

– Paid six bars of amber to the Mumbo Jumbo boys, and set out for Jindey early in the morning. Found this day’s travelling very difficult; many of the asses refused to go on; and we were forced to put their loads on the horses. We reached Jindey about noon. Purchased a bullock, and halted the 6th; fearing, if we attempted to proceed, we should be forced to leave some of our loads in the woods.

May 7th

– Left Jindey, but so much were our asses fatigued that I was obliged to hire three more, and four drivers to assist in getting forward the baggage. One of the St. Jago asses fell down convulsed when the load was put upon him; and a Mandingo ass, No. 11, refused to carry his load. I was under the necessity of sending him back to Jindey and hiring another in his place.

We travelled on the north side of the Wallia Creek till noon, when we crossed it near Kootakunda. Swam the asses over; and the soldiers, with the assistance of the Negroes, waded over with the bundles on their heads. Halted on the south side of the creek, and cooked our dinners.

At four o’clock set forwards, passed Kootakunda, and called at the village of Madina to pay my respects to Slatee Bree. Gave him a note on Mr Ainsley for one jug of liquor. Halted at Tabajang, a village almost deserted; having been plundered in the course of the season by the king of Jamberoo, in conjunction with the king of Woolli. Our guide’s mother lives here; and as I found that we could not possibly proceed in our present state, I determined either to purchase more asses, or abandon some of the rice.

May 8th

– Purchased two asses for ten bars of amber and ten of coral each. Covered the India bafts with skins, to prevent them from being damaged by the rain. Two of the soldiers afflicted with the dysentery.

May 9th

– The king of Jamberoo’s son came to pay his respects to me. Jamberoo lies along the north side of the Wallia Creek, and extends a long way to the northward. The people are Jaloffs, but most of them speak Mandingo. Presented him with some amber. Bought five asses and covered all the gunpowder with skins, except what was for our use on the road.

May 10th

– Having paid all the people who had assisted in driving the asses, I found that the expense was greater than any benefit we were likely to derive from them. I therefore trusted the asses this day entirely to the soldiers. We left Tabajang at sunrise and made a short and easy march to Tatticonda, where the son of my friend, the former king of Woolli, came to meet me. From him I could easily learn that our journey was viewed with great jealousy by the Slatees and Sierra-Woollis residing about Madina.

May 11th

– About noon arrived at Madina, the capital of the kingdom of Woolli. We unloaded our asses under a tree without the gates of the town, and waited till five o’clock before we could have an audience from His Majesty. I took to the king a pair of silver-mounted pistols, ten dollars, ten bars of amber, ten of coral. But, when he had looked at the present with great indifference for some time, he told me that he could not accept it; alleging, as an excuse for his avarice, that I had given a much handsomer present to the king of Kataba. It was in vain that I assured him of the contrary; he positively refused to accept it, and I was under the necessity of adding fifteen dollars, ten bars coral, ten amber, before His Majesty would accept it. After all, he begged me to give him a blanket to wrap himself in during the rains, which I readily sent him.

May 12th

– Had all the asses loaded by daybreak, and at sunrise, having obtained the king’s permission, we departed from Woolli. Shortly after, we passed the town of Barraconda, where I stopped a few minutes to pay my respects to Jemaffoo Mamadoo, a very eminent Slatee. We reached the village of Bambakoo at half-past ten o’clock. Bought two asses, and likewise a bullock for the soldiers.

May 13th

– Departed from Bambakoo at sunrise, and reached Kanipe, an irregular built village, about ten o’clock. The people of the village had heard that we were under the necessity of purchasing water at Madina; and to make sure of a similar market, the women had drawn all the water from the wells, and were standing in crowds, drawing up the water as fast as it collected. It was in vain that the soldiers attempted to come in for their share: the camp kettles were by no means so well adapted for drawing water as the women’s calabashes. The soldiers therefore

returned

without water, having the laugh very much against them.

I received information that there was a pool of water about two miles south of the town; and in order to make the women desist, I mounted a man on each of the horses and sent them away to the pool, to bring as much water as would boil our rice; and in the afternoon sent all the asses to be watered at the same place. In the evening some of the soldiers made another attempt to procure water from the large well near the town, and succeeded by the following stratagem. One of them having dropped his canteen into the well, as if by accident, his companions fastened a rope round him, and lowered him down to the bottom of the well; where he stood and filled all the camp kettles, to the great mortification of the women, who had been labouring and carrying water for the last

twenty-four

hours in hopes of having their necks and heads decked with small amber and beads by the sale of it. Bought two goats for the soldiers.

May 14th

– Halted at Kussai, about four miles east of Kanipe. This is the same village as Seesekunda, but the inhabitants have changed its name. Here one of the soldiers, having collected some of the fruit of the Nitta trees, was eating them, when the chief man of the village came out in a great rage, and attempted to take them from him; but finding that impracticable, he drew his knife, and told us to put on our loads and get away from the village. Finding that we only laughed at him, he became more quiet; and when I told him that we were unacquainted with so strange a restriction but should be careful not to eat any of them in future, he said that the thing itself was not of great importance if it had not been done in sight of the women. For, says he, this place has been frequently visited with famine from want of rain, and in these distressing times the fruit of the Nitta is all we have to trust to, and it may then be opened without harm; but in order to prevent the women and children from wasting this supply, a

toong

is put upon the Nittas until famine makes its appearance. The word

toong

is used to express anything sealed up by magic.

Bought two asses. As we entered the Simbani woods from this town, Isaaco was very apprehensive that we might be attacked by some of the Bondou people, there being at this time a hot war between two brothers about the succession: and as the report had spread that a coffle of white men were going to the interior, every person immediately concluded that we were loaded with the richest merchandise to purchase slaves; and that whichever of the parties should gain possession of our wealth, he would likewise gain the ascendancy over his opponent. On this account, gave orders to the men not to fire at any deer or game they might see in the woods; that every man must have his piece loaded and primed, and that the report of a musket, but more particularly of three or four, should be the signal to leave everything and run towards the place.

May 15th

– Departed from Kussai. At the entrance of the woods, Isaaco laid a black ram across the road and cut its throat, having first said a long prayer over it. This he considered as very essential towards our success. The flesh of the animal was given to the slaves at Kussai, that they might pray in their hearts for our success.

The first five miles of our route was through a woody country; we then reached a level plain nearly destitute of wood. On this plain we observed some hundreds of a species of antelope of a dark colour with a white mouth; they are called by the natives

Da qui

, and are nearly as large as a bullock. At half-past ten o’clock we arrived on the banks of the Gambia, and halted during the heat of the day under a large tree called

Teelee Corra

, the same under which I formerly stopped in my return from the interior.

The Gambia here is about a hundred yards across, and, contrary to what I expected, has a regular tide, rising four inches by the shore. It was low water this day at one o’clock. The river swarms with crocodiles. I counted at one time thirteen of them ranged along shore, and three hippopotami. The latter feed only during the night, and seldom leave the water during the day; they walk on the bottom of the river, and seldom show more of themselves above water than their heads.