Trauma Farm

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR

TRAUMA

F

arm

“Trauma Farm is a passionate memoir of life on a small farm. Brian Brett brings us his own version of guns and roses with wisdom and wit. A great book that asks the reader to read it and then joyfully read it again.”

PATRICK LANE

author of

Red Dog, Red Dog

“If it’s hope you’re looking for, you’ll find it in the fortifying madness of Trauma Farm. You may never want to leave.”

J.B. MACKINNON

author of

The 100-Mile Diet

and

Plenty

“An engaging, quirky narrative of farm life which often reads more like poetry than prose.”

NICOLETTE HAHN NIMAN

author of

The Righteous Porkchop: Finding

a Life and Good Food Beyond Factory Farms

A REBEL HISTORY

OF

RURAL LIFE

BRIAN BRETT

TRAUMA

F

arm

D&M PUBLISHERS INC.

Vancouver/Toronto/Berkeley

Copyright © 2009 by Brian Brett

09 10 11 12 13 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright).

For a copyright licence, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free to 1-800 -893-57 7 7.

Greystone Books

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver bc Canada v5t 4s7

www.greystonebooks.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Brett, Brian

Trauma farm : a rebel history of rural life / Brian Brett.

Includes bibliographic references.

ISBN 978-1-55365-474-2

1. Brett, Brian. 2. Brett, Brian—Family. 3. Authors, Canadian (English)— 20th century—Biography. 4. Farm life—British Columbia—Saltspring Island. 5. Natural history--British Columbia—Saltspring Island. i. Title.

s522.c3b74 2009 c818’.5409 c2009-904051-4

Editing by Nancy Flight

Copy editing by Barbara Czarnecki

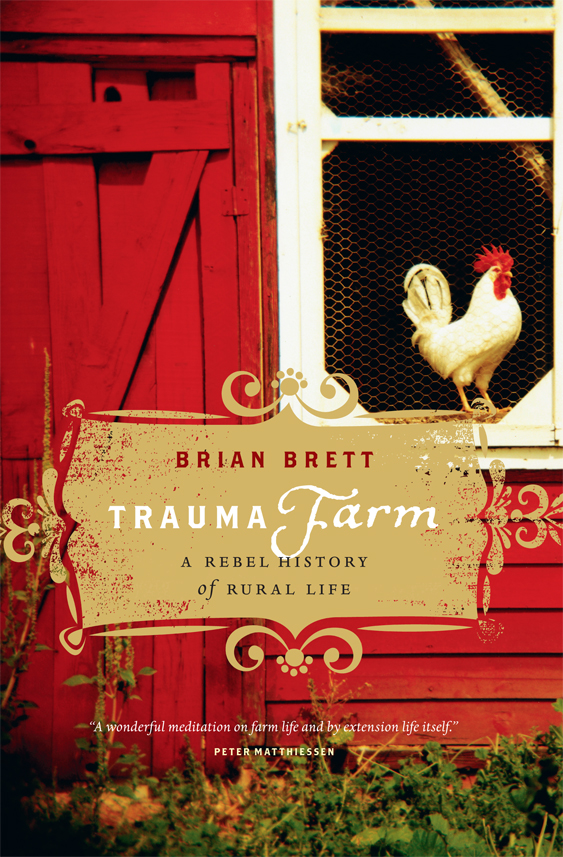

Jacket and text design by Naomi MacDougall

Jacket illustration by Michael Kelley/Getty Images

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens

Printed on acid-free paper that is forest friendly (100% post-consumer recycled paper) and has been processed chlorine free.

Distributed in the U.S. by Publishers Group West

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (bpidp) for our publishing activities.

The author would like to thank the Canada Council, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Haig-Brown House, and the Writers’ Trust for their support.

This book is dedicated to Sharon and the children . . .

and the children of the children . . .

the eagerness of nineteen-year-olds . . . and Beverly

and Mike Byron—teachers and mentors.

CONTENTS

7 Running Dogs and Fellow Travellers

14 One More for the Birds (and Their Friends)

17 Fence Builders and Tool Users

20 A Tour Is Good for the Digestion

21 Regulating a Rebellious Universe

22 Local Living, Local Communities

A

FARM IS BOTH

theory and worms. Once it was the bridge between wilderness and civilization; now it has become a lonely preserve for living with what remains of the natural landscape—a failing companion to a diminishing number of hunter-gatherer societies, a few parks, and the surviving wilderness. There is a science to farming, but one of its by-products is the terrifying logic of the factory farm. There is also a history of traditional practices, some delicious and others scary. Those traditions, along with the small farms remaining, are being crushed by regulation and globalization.

Yet, if anything, the small, mixed farm is a hymn to the lush achievement of our complex world and to ecological entropy—the natural process that creates diversity. Tradition and science and ecology wrapping around each other like a multidimensional puzzle. It’s nighthawks celebrating the dusk with their booming dives, the fields turning gold in the late afternoon light, laughter in the face of the absurd, a bright Spartan apple peeking from behind a green leaf, and the need to produce good food for the community.

We moved into our four-thousand-square-foot log house on a cold January afternoon, eighteen years ago. The shake roof leaked, skylights were smashed, snow drifted through the laundry room, the plumbing was split from freezing. Two of the outer doors were completely gone. Lost. Who would take someone’s doors? You could see outside through the gaps in the log chinking. The sole heat was provided by a pair of wood stoves, both working inadequately. The woodshed attached to the barn contained a forlorn, punky chunk of alder. The kitchen stove hadn’t been cleaned in a year because the caretakers didn’t realize that ashes needed to be hauled from cookstoves. The chimneys were thick with creosote.

I was still in good health then, and Sharon was, and still is, tireless. We were fools for work. We brought our younger son, Roben, nineteen years old and a silent tiger when it came to labour. He was accompanied by a changing cluster of anarchic nineteen-year-old friends, eager for adventure in our world outside the city—Joaquin, Seb, Paul, Gerda, Lenny, Jason. The farm was a romantic escape for them, as well as a way to keep out of trouble, and they crashed in various spare rooms in the house and barn (which had a guest room). The group changed regularly. A few women drifted into the barn, but it was mostly guys, except for Gerda, who became a master gardener and sculptor. Sebastion, easygoing and affable; Paul, brilliant though he kept his genius hidden; and Joaquin, the vocal rebel who questioned authority. They were the most regular. They still whine about how hard they worked for so little. I tell them that’s farming.

We could have probably taken the more economical route of hiring farmhands, since the boys ate like horses and had a tendency to break furniture and tools, but we achieved an enormous amount of work and I loved relearning the world of the young. I like to think we gave them some good directions about living in the world. They all spent varying amounts of time on the farm, working for room and board and wine. There was lots of partying, and very little cash. When we look back now at those first six years, none of us can believe how much we accomplished.

As the initial building, fencing, and rebuilding years drew to a close, I recognized I would eventually write about the farm, but some instinct demanded I find a way to tell its story within the natural history of farming itself. The question is, How do you write the natural history of a farm when such histories tend to follow a linear logic? A farm isn’t logical, as anyone who’s had a foot stepped on by a clueless horse or watched the third crop of peas fail to sprout will tell you.

I realized the only way I could write this memoir was by association—a walk through a summer’s day—the June day of the solstice. A walk that simultaneously remembers winter snows, sunflowers, the dinnertime song of the sheep, history, and the taste of acid soil—a sublime landscape framed by laughter and absurdity and shock—an eighteen-year-long day that includes both the past and the future of living on the land, tracing the path that led hunter-gatherers to the factory farm and globalization. Just as we have learned to respect the educational and social fountain of Native teaching tales and their great resources, it became obvious to me that the tradition and science of farming could also be told through the magic of story.

Rural living is an eccentric pursuit, in the same way that beauty is an eccentric pursuit—an exercise in nonlinear thinking as much as a series of rational steps. It’s both a logical and an intuitive act, like running an obstacle course; it seems easy until you attempt to make a machine that can do it.

Although our business name is Willowpond Farm, we came to refer to this land as Trauma Farm, because we soon realized beauty also demands a little terror and laughter, and that this story would have to follow the form of the farm and not the romantic or scientific myths we inflict upon it.

Farming doesn’t have a long history by evolutionary standards. The earth is approximately 4.5 billion years old, whereas Emmer wheat was first utilized around nineteen thousand years ago. Its systematic cultivation began a mere twelve thousand years in the past, closely followed by Einkorn wheat. That’s when the small farm began. These two exquisite grains remain in cultivation, though mainly in small pockets in Ethiopia—and in North America, where seed savers are attempting to protect endangered grains. Rice, although the genus appeared 120 million years in the past, wasn’t cultivated until ten thousand years ago.

The discovery of seed collecting marks a paradigmatic change in human evolution toward what we optimistically call civilization. Cap this with the invention of record keeping, and suddenly, in the five thousand years since writing began, the rest of the planet is in trouble. Estimates of our population in 10,000 bc average around 5 million people. Today, we are 6.5 billion individuals on an endangered planet. The historian Ronald Wright notes our recorded history equals the combined lifespan of only seventy people, counted from slashes in wet clay, around 3000 bc , to the billions of binary codes in the hard drives of today.

Modern economics and simplistic thinking have made farming even more cruel and dangerous than it has been historically—thousands of pigs clamped screaming into sterile environments; fields flooded with contaminated sewage sludge; frog genes crossed with tomatoes; potatoes that are also pesticides in the brave new world of genetic modification.

Fortunately, a new generation is reconsidering the concept of the modern farm, inventing new methodologies and building on traditional knowledge.