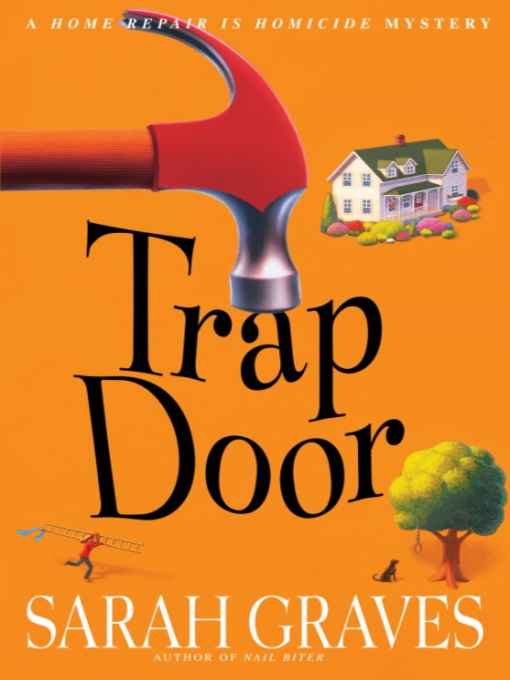

Trap Door

Authors: Sarah Graves

Synopsis:

Graves’s humorous, well-constructed 10th home improvement cozy (after 2005’s Nail Biter) finds Jacobia “Jake” Tiptree, former money manager to the mob, still hard at work on her 1823 Federal-style house in Eastport, Maine. But she’s got more to fix than a roof caving in: her dead ex-husband, Victor, is haunting the house and her friend Jemmy is on the run from hit men, including the ruthless Walter Henderson, who’s also made his home in Eastport. A local young man who had been dating Walter’s daughter has gone missing, and when Jake and her friend Ellie show up at the assassin’s home, they make a grisly discovery in his barn. Graves weaves in plenty of home repair tips and a correspondence between two antiquarian experts concerning a mysterious book Jake has found in her cellar for an outing sure to please series fans.

By

SARAH GRAVES

Copyright © 2006 by Sarah Graves

Over a long, successful career of killing people for money,

Walter Henderson had never before snuffed out a personal enemy. He’d made a habit of keeping his private life and his business affairs separate, and planning to break that habit now aroused a variety of new emotions in him, none of them pleasant.

Anxiety, resentment, and the kind of bone-deep reluctance a lazy schoolboy might feel, facing a pile of homework… these were not sentiments with which Walter Henderson, a paid assassin, had any significant experience.

Thus as he sat waiting in his comfortable leather armchair for the inevitable to occur, he tried yet again to come up with some other way out of the situation in which he found himself. But he’d been over it all a hundred times in his head already and he’d found none.

Because there weren’t any. So now here he was.

I’m not even supposed to be doing this anymore,

he thought irritably. With one exception—a loose end he meant to tie up very soon—he’d decided that his death-dealing days were history.

But apparently resolutions really were made to be broken, he thought. Then came the sound he’d been waiting to hear: stealthy footsteps on the gravel driveway outside, not far from his open window.

Walter looked up from the book he’d been pretending to read, in the warm pool of light in the den of his large, luxuriously appointed house in Eastport, Maine. It was late. The housekeeper had gone home to her own house, and his teenaged daughter Jen was already in bed.

Or so she’d tried hard to convince him as she’d headed upstairs an hour earlier: clad in pajamas, carrying a glass of milk and a handful of cookies, and yawning elaborately.

Smiling with affection, thinking how pretty she was with her golden tan, strong athlete’s body, and sun-bleached blonde hair, Walter had bid his daughter a fond good night. Then he’d built a fire in the enormous granite fireplace that formed one whole wall of the room, piling it with chunks of aged driftwood so it flamed extravagantly before settling to a fierce red glow.

After that, with a scant two fingers of Laphroaig in a chunky cut-crystal lowball glass to keep him company, he’d sat down with his book to wait. Despite the chilly spring evening the fire let him keep the window open, admitting salt air and whiffs of wood smoke along with the distant, varied hoots and moans of the foghorns on the dark water a few hundred yards distant.

Now Walter sat very still, listening to the sound of cautious movement outside, a whispery crunching on stones that someone was trying to minimize.

To no avail. That you couldn’t approach the house without traversing an expanse of pea gravel was not an accident, any more than the elaborate alarm system, heat-and-motion detectors, or closed-circuit TV cameras that Walter had installed when he’d had the house built.

All turned off now, of course. Walter didn’t want any record, electronic or otherwise, of what transpired here tonight. Just to be sure, he’d had an old buddy of his run up from the city a week earlier to disarm the devices, taking care to make it appear that the central controller circuits had silently malfunctioned.

In the unlikely event that anyone checked. Walter listened a while longer to be certain it wasn’t only a wild animal out there, a deer or raccoon or maybe even a moose. There were plenty of them on the island where Eastport was located, seven miles off the coast of downeast Maine and another thousand or so from the neon-lit nightlife Walter Henderson was used to: pimps and hookers, loan sharks and dope addicts, pushers and grifters…

All in the past now, he reminded himself without regret. And from the sound of it, tonight’s visitor was indeed human. A glance outside confirmed this; there was a light on in the barn, faintly illuminating a high square of window.

Which there hadn’t been the last time Walter looked. He waited ten deliberate minutes, then laid his book aside, got up, and removed the loaded pistol from its usual place in the upper right-hand drawer of his desk. Placing the gun in his sweater pocket, he padded from the room, pausing in the dark hall but not bothering to go upstairs to see whether or not Jen was really asleep.

He knew she wasn’t, that the yawning and milk getting and elaborate expressions of tiredness had all been an act. For the past few weeks, ever since she’d graduated and come home from the exclusive New York boarding school where she’d spent her high school years, she’d been sneaking out via those same back stairs nearly every night to meet a boy.

And not just any boy. Walter knew it was that worthless little helper the carpenters had brought with them last summer when they arrived to rebuild the barn. Which by itself was okay, bringing along a useless helper. He understood that. People had expenses to cover and sometimes they resorted to methods.

Charge high, pay low… it was how the world worked. Probably the contractor got a cut of the materials, too, in an arrangement with the supplier. All standard business practice and all right as rain as far as Walter was concerned, as long as nobody got too greedy.

The kid, though. The kid was something else. Because when the barn job was done and the carpenters had all gone, the kid kept coming around. Doing another kind of job now, wasn’t he? On Walter Henderson’s daughter.

The thought stopped him in his tracks: Jennifer. His pearl, the only person he knew of in the world who hadn’t somehow been contaminated or befouled. The idea of some mangy little nobody with grimy fingernails even thinking about touching her…

Well, but it

wasn’t

thinkable, was it? That was the whole point. Back in the city he’d have snapped the kid’s neck with his two hands, and that would’ve been that. Dumped him in a landfill or in the trunk of an abandoned car; if push really came to shove there was a sausage factory in Paramus that would take the kid, no problem.

But Walt couldn’t do any of those things here, not without screwing up his plans for finishing off that other loose end. And now it seemed no matter what else he tried, he couldn’t get rid of the kid.

Padding quietly in the plush moosehide L.L. Bean moccasins Jennifer had given him for Christmas, he slipped down the hall to the silent kitchen, past dimly gleaming appliances and the wall-mounted panel for the alarm system.

The panel’s bulbs glowed green, meaning the system had been armed. But according to Walt’s gadget-literate buddy, “on” commands weren’t reaching the devices the system controlled.

Walt hadn’t told Jen about that, though; no need. For all she knew, the alarms worked as they always had. Thinking this, he continued along the dim passageway past the utility room where a pair of Irish wolfhounds stayed when he needed them to be out of the way.

A low

wuff

came from inside the room as he went by. The dogs’ nails clicked on the tiled floor as they paced uneasily, alerted by the sound of his presence. Warning growls issued from their throats.

Walter made a face. Ideally, the two expensively bred guard animals should have remained utterly silent. But he hadn’t been able to stomach the severity of the aversion training required to accomplish this.

Or to make them bite, either. Yet another sign that he was getting soft, he decided. He’d retired at the right time. But not too soft to do what needed to be done this evening; dogs were one thing, snot-nosed little daughter-molesting punks quite another, he reminded himself without much effort.

Quite another, and not much effort at all; like riding a bike. “Easy, guys,” he murmured to the dogs as he let himself out the back door, easing it shut behind him. He paused on the flagstone terrace overlooking Passamaquoddy Bay.

Across it the windows in the houses along the distant shoreline of Campobello Island glowed distinctly. Below them the emerald green lights nearer the water marked harbors and jetties, while to the north the white beacon of the Cherry Island light swirled slowly, strobing the night.

He stepped from the terrace to the lawn, wincing at the icy breeze. April may be the cruelest month, he thought as he made his way downhill toward the squarish dark shape of the barn outlined on an even darker moonless sky, but in Maine at night you could pretty much count on May being a mean bastard, too.

The light in the barn had gone out. Pausing, he hefted the gun in his pocket as easily as other men might handle jackhammers or drive heavy equipment; tool of the trade. When he slipped inside the barn the scent of the new wood mingled with the sweet, grassy smell of the straw bales piled in the loft.

But then came a hint of Jen’s expensive perfume, faint but enough to send fresh fury coursing through him. For an instant he imagined the two of them up there, visualized them freezing together in fright at some slight sound he made.

The thud of his heart, maybe, or the grinding of his teeth. Or the hot slither of the muscles in his forearms as his fists clenched and released.

Clenched and released. The boy shriveling, Jen scrambling to cover herself… Walter pushed the thoughts away, smelling now the sharp reek of gasoline from the big lawn tractor in the corner. Behind it on hooks, although he could not see them, were gardening tools, the curved scythes and heavy shears, cutting and chopping implements. All with their blades freshly sharpened.

Walter moved soundlessly in the utter blackness, needing no light once his predatory instincts kicked in. He knew how to do this, and he knew his way in the dark. To his right were the loft steps and behind them an area under the loft, originally meant for open space.

But Walter’s housekeeper, a habitually silent and thus thoroughly satisfactory employee he’d brought with him when he moved here from the city, had surprised him by suggesting that the area be enclosed to form an office. That way whoever Walter hired to oversee the grounds and the animals wouldn’t end up tramping in and out of the main house. So a room had been built there, unused as yet and with the loft’s original trap-door opening still piercing its ceiling.

Guy ever needs to escape out of his own office, he can go straight up, Walter had thought with grim humor. If he can jump that high. Unlikely, though, that the kid Walter was after tonight had gone

down

into the office space.

Because the jumping part was no joke; it was a good fifteen feet from the loft to the concrete floor below. And the office was locked; if you got into it from above, there was no way out.

Walter felt the tight smile vanish from his lips.

No way out for me, either

.

Or only one way. And damn it, the whole thing was really all his own fault, wasn’t it? He’d been firm enough in forbidding Jen from seeing the boy, all right, just not sufficiently clear about the consequences of disobedience.

And he knew why. Raising the child by himself after her mother’s death, Walter hadn’t wanted Jennifer to be afraid of him. He couldn’t bear seeing the knowledge arise in her eyes—as it had in the desperate, imploring eyes of so many others—that he was dangerous. Thus he had failed to confide in his daughter certain important details about himself.

Such as what he did for a living: that he solved problems for people. Serious problems, ones so difficult and unpleasant that they could be taken care of only by force.