Transmigration (27 page)

Authors: J. T. McIntosh

enough to admit it to himself and to Rodney. The human brain was still

comparatively unmapped territory. Rodney had never been operated on

and there had been no real psychiatric treatment. It had been thought

that he could not possibly respond to it, being capable of only a few

meaningful sounds that meant he was hungry or thirsty. or wanted to go

to the bathroom.

brain that was not normal suddenly going right.

Paradise. Indeed, the doctor was clearly reluctant to let him sleep even

that night in his old cell.

about what might be coming, being too concerned over setting the past

and the present to rights to have time to consider the future.

in Cumberland . . . "

confidence than he probably felt, Dr. Brooke had said he was quite

capable of traveling by himself. It was one of the trusting gestures

made by psychiatrists which didn't always come off.

children in swimsuits ran past him, the girls chasing the boys. He looked

at them with pleasure.

a name. There was no coincidence in his life.

it, but it didn't matter. He needed no proof.

all tragedy. Rebelling against her humdrum life with Baudaker, she had

an affair with another man, a worthless man, a subnormal man. And she

didn't know what to do when she found herself pregnant.

senseless, motiveless, so shamefully wrong. Besides, the baby would not

be normal. She knew that from the start.

public care and went home to see Baudaker once more. Perhaps if he had

been cruel it would have been kind. Instead, he was overpoweringly glad

to see her back.

never tell Baudaker about it. It would not add to his happiness. But it

fitted into Fletcher's cycle so neatly it had to be true.

with small shops on both sides, cars parked on cobbles off the main

road, pretty young mothers pushing prams and leaving them outside shops,

children everywhere, running, shouting. Several people smiled at him

and he smiled back.

could be considered dirty, untidy, unattractive and unwelcoming if people

were predisposed to see it like that. Or it could be. as Rodney saw it, an

ideal place to grow up and find oneself, if such a thing were necessary.

but not unfriendly. At least the iron gates were wide open.

but he did not. He wandered round the old building and found that at the

rear the gardens were lovely. Several children passed him, staring at him

curiously. They were, sadly, quite unlike the shrieking brown children

in the town. They were too clean, too solitary, too cautious. Several

of them had calipers on their legs, and some had wasted limbs. But most

of them smiled back at him.

indicated that the children who could take pleasure in gregarious play

were doing so. For the most part, he saw those who could not.

to be freedom in a place like this, or it was valueless. Life, too,

offered freedom. You took it or you put yourself in chains.

cruelty and intolerance and boredom and frustration. But these were the

obstacles in the obstacle-filled race of life. Anyone lucky enough to get

a second chance in life ought to be able to make light of circumstances

twenty times worse than he was likely to encounter here.

haven.

almost at the moment of death and, possibly, revelation would have

to be considered sometime. But they were not the sort of things a

thirteen-year-old boy had to bother his head about for a long time. His

very age, independent of anything else, gave him at least half a dozen

years' grace before he could take any positive place in the world..

girl. She wore the navy pants of a child and the casually tied suntop

of a pretty and well-shaped woman. She was brown and was the loveliest

thing he could recall seeing in his life.

know me?"

names, and just for convenience I said Fletcher,"

world, isn't it?"

possibly call me Mr. Fletcher."

the most beautiful girl in the world. He was in no doubt about that,

though he remembered Gerry had thought much the same about Daphne and

Ross about Anita. He had nothing against Anita or Daphne, but anyone

who preferred them to Judy needed his head examined.

Mr. Fletcher."

he said.

lost his balance and clutched her. Her warm brown flesh felt even more

wonderful than it looked. Thirteen he thought with momentary gloom. Why

couldn't he and Judy have been five years older?

Judy. "What on earth's that?" he said.

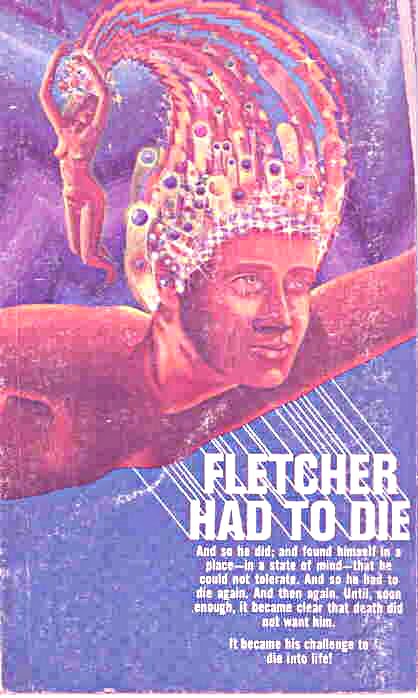

FLETCHER HAD TO DIE

FLETCHER HAD TO DIEAnd so he did; and found himself in a

place -- in a state of mind -- that he

could not tolerate. And so he had to

die again. And then again. Until, soon

enough, it became clear that death did

not want him.

It became his challenge to

die into life.

Other books

40 Something - Safety by Shannon Peel

Cowboys & Angels by Vicki Lewis Thompson

Make or Break the Hero (The Hunter Legacy Book 4) by Timothy Ellis

Precious Stones by Darrien Lee

Journey to Bliss (Saskatchewan Saga Book #3) by Ruth Glover

Death of a Teacher by Lis Howell

Hunters (Spirit Blade Part 1) by M. A. Nilles

Curves for the Werewolf (Paranormal BBW Erotic Romance, Alpha Wolf Mate) by Cassie Laurent

Multiplayer by John C. Brewer

Carnage on the Committee by Ruth Dudley Edwards