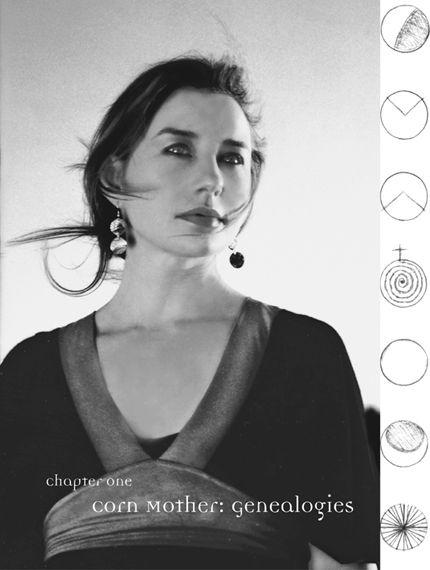

Tori Amos: Piece by Piece (4 page)

Read Tori Amos: Piece by Piece Online

Authors: Tori Amos,Ann Powers

This goes back to why I'm still around. Usually I'm a pussycat, but pussycats can become big kitties really fast if necessary. People always think there's this Svengali behind the scenes. Well, then, there are many. There are a hundred. Karen Binns is one of them. John Witherspoon. Matt Chamberlain. Neil Gaiman. Duncan Pickford. Mark Hawley Chelsea Laird. Marcel van Limbeek. In the end, there are thirty people who are very instrumental, but people change, the lineup often changes, and I'm still able to sell out three nights at Radio City. So then when

somebody still says, “Oh, I wonder who's figuring all this out for her,” I say, “Tell me who it is, so I can call them and get a night off.”

The main thing with Tori that I've seen from day one is that she's been entirely consistent in what she wants to do and what she wants to put out there, and the kids have never felt alienated. And we've gone from one generation to the next among her fans—now we have the original cohorts’ little sisters. The older ones may have moved on, but they have passed the torch. Tori is always planting these seeds for the next kids that come, and we've seen that happen: we're seeing the little kids coming out now.

Tori represents the woman who fights for the world. She fights for her children or fights for her man; she fights to make sure everybody's eating okay; she fights for the words that need to be said. She's always fighting. And if she's fighting, that means she has to be in touch.

Sometimes you are forced to defend your beliefs. Sometimes you are forced to look at relationships that aren't positive anymore. There are times when I have had to make peace with the fact that I am at war. And sometimes you have to fight those who do not want love to conquer all.

Now, backstage at an undisclosed arena where the sweat of athletes is still perfuming my makeshift dressing room, my many conversations with Ann Powers have begun.

“Ann,” I said, “if we are going to spend two years working on a project together, we need to get a few awkward conversations out of the way.”

“Tor, I've been dealing with awkward conversations professionally for twenty years. Have you ever tried to get something quotable from an exhausted lead guitarist after a three-hour stadium show, when he's got a seventeen-year-old groupie waiting for him in the back of the tour bus? Whatever you have to say can't be harder to take than that. Proceed.”

I did. “You come from the journalist side. I come from the artist side. It can become offensive. I'm sure from your side as well as from mine.”

“Well, it's true everyone expects us to be enemies. And in some ways we are. My job is interpretation. Yours is art, which often benefits from mystery. And while I've met many very articulate musicians, most seem almost threatened by detailed questions about their work, which makes interviewing them frustrating. It's as if they expect me to misunderstand them.”

“No arguments here, Ann. Likewise, I may have spent only forty minutes with a journalist, but in that time I will have tried to open up the shutter—undress the obvious answer to get a more compelling response that will jump off the page. And then what happens? The article comes out and I can't even recognize the journalist that I met from the biting, vitriolic person that is writing about our time together.”

“Well, some writers

are

just nasty—not unlike that charmer with the groupie on the bus. And even the nice ones have egos. We view our work as a creative process, too, and sometimes the artist's process gets in the way of ours! If I've decided a song means something—say, that “your cloud” is about your Natashya—and you tell me something different—that it's about Hamlet's ghost—I might just want to contradict you. I can't just assume you know everything that the song's about, either. As you yourself have said to me, meanings can change and emerge over time. Maybe I

am

right …”

“You know the funny thing is, Ann, whenever I start asking a journalist questions, they either start to cream in their pants or run out of the room.”

“Hey, it's more fun for me if we're friends, and friends don't just nod and agree. But let's be absolutely clear. I'm the one opening up the drawers here. And you realize, we will have to discuss some painful events in your life. I can't be my usual, sweet interviewer self all the time if I'm going to get—or help you get—what we need for this book.”

“Look, Ann, I know you're going to probe. Rather you than a proctol-ogist.”

She laughed and I continued, “Or a shitty rock journalist.” “Fair enough, Tori. And I thank you for not being a boring rock star.” Ann and I decided to strip our roles back to basics. We are both women born feminists in the 1960s. We are both married. We are both mothers. We are both in the music industry. Traditionally we are enemies. But for this project to be effective, I had to allow Ann to expose Tori Amos. And Tori Amos's inner circle. And me.

ANN:

Our mother is the ground we stand on, and the earth itself is our mother. How many people have believed this, over the centuries? Society itself began with kinship, lineages marked by blood and love, while civilizations took root in relationship) to the places where people settled and learned the land. The idea that the world was born of a woman is common in myth, across continents: in Africa, Asia, the Mediterranean, northern Europe, and the Americas, such stories abound. The Genesis story of a lone male God making life with a lift of the finger has achieved cultural dominance, but beyond that bragging tale of six days’ labor are others that present Creation as an ongoing process, undertaken by a matriarchal force nourished by her family's respect and love.

Throughout the ages, people have chosen gods to suit their apparent needs; similarly, an artist can view her personal acts of creation in light of various sources. She can thank her ego alone, but that is dangerous—the limits of an individual's personality can quickly turn genius into a dry spring. She can acknowledge her peers as inspiration, cite the demands of the marketplace and the influence of various schools, but influences not so carefully chosen also cannot be avoided.

Every artist is born in a place, within a family, and though she may leave those sources far behind, they remain within her. The achievement comes in acknowledging those origins without being devoured by them. The Cherokee have a story that relates to the need to find balance between personal ambition and accepting life's offerings:

Selu, the Corn Mother, lives with her grandsons in the mountains. The young men are hunters, and Corn Mother provides the staples that round out their meals. The men want to hunt and hunt, and this greed for meat makes Corn Mother sad, yet she loves her descendants and does not challenge them. One morning her grandsons spy on Corn Mother as she makes the corn, which falls

from her body whenever she slaps her sides. This terrifies the men, and they reject her. She withers, but before dying instructs them to bury her in the earth and tells them she will arise again as a plant that will need to be cultivated. Corn Mother does as she promises, but in her new form she cannot be blithely generous. People must learn to cultivate her; they must earn her fruitfulness. With this lesson Corn Mother teaches humankind the need for balance and the love of nature's gifts.

Tori Amos heard the story of Corn Mother from her grandfather as a girl, during summers spent with him in North Carolina. The love of the earth was ingrained in her, along with an awareness that her own talents were a blessing she could not take for granted. Her Cherokee blood is one element in the complex weave of influences that created Amos as she grew toward the moment when she could begin, respectfully, to create herself.

“The grass. The rocks. The trees. Don't care nothin’ about who ya are or who ya think ya are or who ya pretendin’ to be.” Poppa would be in fits of tickles by that saying. “And Shug … [what Poppa called me—short for Sugar Cane and Shush all mixed up], Shug, when ya think yer mighty like a mountain ya might wanta think of being a Rock Nurse. You didn't hear yer Poppa say Rock Star. Or Night Nurse. I'm sayin’ Rock Nurse, Shug. Ya know what that is? That's somebody who's needin’ to take care of a rock for a year before they go and hurt themselves tryin’ to move a mountain. And after a year of being humbled by how much more a rock knows than Jack's Ass, then they'll be seein’ stars. The real ones, Shug—remember those?”

My mother's father, my Poppa, had perfect pitch. He rocked me to sleep ever since the day I was born, singing with a tone that reminds me of sunlight

shining through black strap molasses. It was a pure velvet tenor voice. He and my Nanny had a town life—he would shoot pool, they had culture. I remember every Saturday Poppa and Uncle John would bring home chili dogs from the pool room so that Nanny would have a break before the big Sunday family dinner. Nanny was a four-by-four. Four foot eleven inches and 214 pounds. Poppa would say there could never be too much of Nanny to love. When no one was looking, he would bring her a flower that he picked up on his storytelling wanderings, give her a kiss on the cheek, and say, “This flower wished it was as perddy as you, Bertie Marie.”

Nanny grew the garden. It was tiny, but it enticed me because of the begonias and the honeysuckle. It was wedged up against the Lutheran church parking lot. Nanny didn't want to unravel the covert darkness of a small town. She just wanted to uncomplicate everyone's life once they came into her home and sat at her table. Nanny's table would wrap its arms around you with soul food. The biscuits, the creamed corn, the corn on the cob, the corn pudding, the corn bread in the skillet, the whole thing. Fried okra, pinto beans, turnips, and mustard greens—“Sweeter than col-lard greens,” she would say. And in a way, Nanny's love was in the food. It was very much that kind of twelve-people-for-lunch-every-day kind of thing. She was this warm, warm creature who wasn't overly educated. When Poppa died, when I was nine and a half, she started to lose her mind. Patsy Cline's “I Fall to Pieces” finally started to make sense to me then.

Poppa was born Calvin Clinton Copeland and answered to C.C. or Clint as a boy. But I only heard most people call him Poppa—at the shops in town, at choir where he sang every Sunday and collected pieces for his stories—whether inspired by the organist making eyes at the minister or the manager of the hardware store running off with the pharmacist's wife … Poppa, unlike Nanny, did want to unravel the covert darkness of a small town while we all sat together on the porch snapping beans— Nanny, Granny Grace, Aunt Ellen, me, and my mom, Mary Ellen.

Nanny and Poppa each had a full-blooded Cherokee grandparent who was on the Eastern Cherokee tribal rolls. They were spiritually drawn to the old ways and chose to stay on their native ground. From the Smokies of east Tennessee to east of the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina, they settled on old Cherokee ancestral land. They understood that this ancestral land was their sacred spiritual source, just as the Lakota will say the Black Hills are theirs. This is where I spent all my summers as a child.

Poppa wouldn't give up on me.

“Focus on that tree, little 'un,” he would say. We're talking around 1967, when I was four.

“Come on, Poppa, I'm hungry.”

“You almost have it. You can get this. Feel her strength. Let her tell you her story. Now sit still and let her play you like you play that piano.”

As I got older Poppa would push me.

“Can you hear the ancestors, little 'un? They are not happy today.”

“No, Poppa, I can't really hear them.”

“Then ya just aren't listenin’, are ya? Now don't you roll those eyes at me. Yer gonna needs to know this one day.”

“Know what?”

“How to tap into a place's power spot.” He would bend down with his hand, touching that sandy Carolina soil.

“What are you talking about?”

“Hum. Ya gotta hear the hum.” He looked straight at me as if I were being told the most important piece of information ever.

“The hum?”

“Yes, the hum of the Great Mother. Let this sink in. Every inch of this land has been walked on by somebody's ancestors. That means there are events, conversations, killins’, singins’, dancin’—Lord almighty—

squabblin’, you name it. It has happened. So ya decides first what ya needs to tap into. Find the way in. Ya must hear the tone. Follow it and yer probably at a vortex.”

“You believe this, Poppa?”

“I know this, Shug: the white man don't know.”

“Careful, Poppa, Dad's white.”

“Hmm. He's Irish-Scottish. That ain't white. They been fightin’ the white man who takes the land—takes the land till the Grim Reaper comes up and taps the white man on the shoulder and says, ‘No weaslin’ outta this one, yer time has come.’ It used to tickle your old Poppa to see a white man turn white as a ghost.”

“Okay, in English.”

“Most people nowadays, Shug, don't see. Don't feel. Don't hear any-thin’ that science can't prove. A hundred years ago people said a man would never fly.”

“But he couldn't.”

“Yes, granddaughter. Yes, he could. He just hadn't figured out how. The Eagle Dancers knew man could fly It was only in this dimension that the mechanics hadn't been worked out.”

“So now we know how to fly”

“Only in the physical, granddaughter, not in the spiritual. Back to your studies, and find me a vortex before lunch.”

“Does my hungry tum-tum count?”

“Nope.”

I somehow knew that this was where I had to learn and train. Poppa would talk about shape-shifting, the practice of shifting the containment of the human condition in order to open it up to other forms of consciousness.

We'd take walks every day, and he would communicate the way he saw the world, which was that there was life in all things, that there was a kind of knowing in all things. Like anyone, according to Poppa, I'd have to retune my own receiving information system, in my own being, to be able to hear the unique harmonics—thereby understanding the language of the spirit world. What I do know is that he knew this language. I cannot tell you I quite understand how he did, but I watched with amazement as he would communicate with nature, and he seemed to understand it—he seemed to bask in his relationship with it.

I did not have this ability and somehow I knew I never would, but at age four I began to feel something else. I began to feel the music inhabiting me. I'd say to Poppa, “Songs are chasing me,” and he would say, “Shug, slow down and let the song's stories talk to you. Tell them ya've got room around the fire for 'em and their friends. And ya listen to 'em, Shug, ya listen up now, and they'll teach ya things ain't nobody on this earth can begin to think about even tryin’ to blow in those kind of trade winds.” He'd say, “Don't be afraid, Shug, my grandmother Margaret Little told me the same thing when the stories started bendin’ my ear as a little rascal. She'd say, ‘C.C., if the stories don't knock the fire out of ya, then they just might warm that little rascal heart of yers.’ ” He told me from the beginning, “The stories have always come a visitin’. And the stories have always said, ‘C.C., this is who we are and you'll use your own language to tell folks about us, but this is our framework.’ ” And he said he could see them. I have the same experience, even to this day—I can tell you how I see mine. I see the songs sometimes in light filaments. It's a light filament of architecture. The light resonates with a musical tone, but it is a definite structure. Then I translate the light structures into a musical form.

Poppa would talk to me about how there were just certain places that we are called to, all over and around the world. You can't explain it, but

you just feel for whatever reason that you have access. You know when you're comfortable walking down those streets and knowing you're not going to get mugged. The place knows the codes that you carry. And your codes know the place instinctively. So point being, when Poppa was learning how to access different vortexes, he was in his power center. He'd learned the power of embracing the land from his own grandmother, who had insisted that they stay within Cherokee land, which was thousands of square miles. So her whole life she spent circling Cherokee land; that's where her turbulent yet compelling story broke away from the root, in north Georgia, north of the Cherokee capital, Echota. It's still there.

Both Nanny and Poppa inherited colorful but complicated and difficult family histories. Poppa's grandmother Margaret Little survived the Trail of Tears. In 1838 and 1839, she was hearing about the roundups of Cherokee families whereby they would be taken to internment camps. This devastation of the Cherokee and other Eastern tribes had been cemented in 1830 when President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act. Chief Junaluska of the Cherokee tribe pleaded with Andrew Jackson, yet even though that chief had driven his own tomahawk through the skull of a Creek warrior and saved Jackson's life at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1813, Jackson's greed for Cherokee land was stronger than any sense of debt or moral or ethical principles. The modern Cherokee Nation had founded its own constitution in 1827, after Sequoyah (also known as George Gist) had officially written down their oral constitution and official records, using a syllable-based lexicon consisting of eighty-five characters.