Tori Amos: Piece by Piece (20 page)

Read Tori Amos: Piece by Piece Online

Authors: Tori Amos,Ann Powers

Then there are occasions when you have to mask your characters. You can't reveal who a person is in a song, even to that very person. I have songs, I must be honest, that to this day people don't know are about them. They'll say, “God, that character is really awful. I would never want to meet them.” And it

is

them. But I won't give it away. Because once you blow your source, you're blown forever. No one would want to be around me. Plus, I might not agree that the character is awful. Certain archetypes will push it, and, let's face it, sometimes changes are painful at first.

Since I was three, I've been writing songs and changing certain elements so nobody could find out whom I was actually writing about. I started writing about the church and what was going on and who was diddling whom, the chat you get in choir. I wrote about the puritanical witchburner

old prunes that were holier than thou. The Freak, whose daughter was in the choir, masquerading an upstanding-citizen image, all the while drooling behind his hymnal every time we sang the word “virgin.” My friend Connie and I would be like, “Here it comes, here it comes,” and,

bingo

, Freako's drool just misses the hymnal. I began to learn very early that there were a lot of shenanigans going on. And it did really shock me, and my mother's the type of lady who would not discuss that kind of stuff. She would not be drawn in.

But even as a kid, I knew that I was a composer and that I had to put this information somewhere in order to keep a record of the truth, because ninety percent of what was really going on got turned around and swept under the carpet. Soon certain events just faded, like paint does on walls; consequently you can't remember why you have such a bee in your bonnet about certain things that get brought up in conversation. So I decided to avoid being a loose cannon. My only choice was to put what I saw into the music. When you're a kid you can't just leave the house and move away—well, for me that wasn't an option, mainly because I adored my mother. But sometimes I felt as if “those who are they” and their need to control were trying to infuse me with their belief system and their opinions so that I would cease to be a heretic. Knowing that I couldn't do anything about my surroundings and everyone's beliefs around me, that as far as Christianity goes there was one Book, and one Book only—there was no place to run, there was no place to hide from being inundated by what I considered to be not the whole truth. But I had no proof. To survive Christian boot camp for twenty years, and I don't mean Gnostic Christian, I had to create sonic paintings that I could step into just so I could nurture my own beliefs while surrounded by the Puritanical Christian Army's “Gospel of

Forward March”

and “Holy Communion of the

Inverted Rope Descent.”

The people I love, and even those who just happen to be around a lot, unquestionably make it into the work. They're like ghosts. They walk through songs; they come in and out of doors. But I've always said that the songs have their own lovers, and birthplaces, and beliefs. Maybe I did feel something with Mark on the second verse or the seventeenth bar, or something he says will show up in a song that's actually about women arguing with each other. There are moments of Mark in songs. He's part of “Lust,” obviously. But that's also about a story of Jesus and the Magdalene being lovers. Lovers throughout time. I think all of us carry the Lover. That's true of many archetypes. How could I possibly own any of them?

ANN:

Few stories that mark the long scroll of myth are as moving as that of Demeter and her daughter Persephone. The virgins kidnapping and forced marriage to Hades, the god of the underworld, is traumatic enough on its own, but the tale's truly woeful figure is Demeter, the mother whose grief is so great at the sudden loss of her child that it plunges the entire earth into barrenness. Hers is a

fate of wandering and rage, of a pain so great that it destroys everything around it, and—when the males who run the show grant Persephone the right to return

for only part of each year—of a maternal fulfillment forever tinged by loss. This story, which probably originated in a simple need to explain the turn of the seasons, exposes such basic qualities of the soul—the fear of death that can never be

fully mitigated by the acceptance of life's cycles and the unsettling, indeed sometimes perilous magnitude of maternal love—that it became the basis for the Eleusinian mysteries, the central religious rites of ancient Greece.

Demeter's spirit continually resurfaces in the modern world. Motherhood, always an affair that pulls open the heart, has become complicated by women's changing sense of themselves and their place. Some, having put off pregnancy in

favor of self-fulfillment, endure years of struggle to conceive. Once children do come, mothers must fathom how to give them everything possible without losing their own identities in the process. The work of motherhood remains obscured by ideas of what should come naturally to women, its joys trivialized by sentimental renderings.

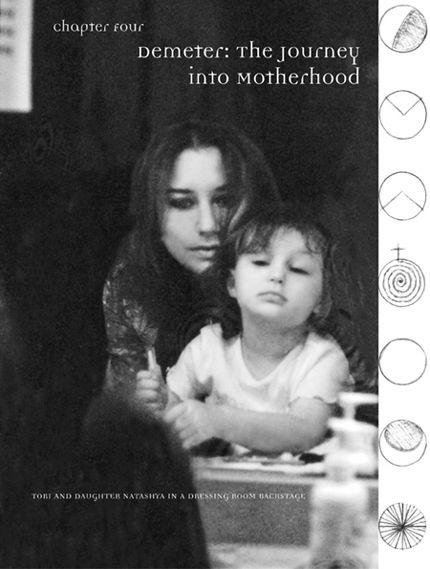

Tori Amos came to motherhood on a hard and treacherous road. Before giving birth to her daughter, Natashya, she had to face her own physical limitations, the duplicity that can surface within the “fertility industry,” and the disconnect between the hard-driving entertainment world and the more cyclical demands of starting a family. Natashya has brought Amos a sense of peace, but also made her

fiercer than ever. Growing into motherhood has given Amos new ways to think about music, love, loyalty, and her own heritage. Now, along with other women artists of her generation, she is working to create a new balance between the “public” dominion of work and creative expression and the “private” enclave of child rearing. Acknowledging the unified nature of these efforts without being willing to compromise either, she offers a very personal perspective on the feminine coming to terms with itself.

My mother taught me about sovereignty, a sense of your own authority. She was the most educated person in our family. She wanted to be a college teacher. On one level I think it's unfortunate that she didn't continue with her career once she had her kids, but what she did get from the world she brought back to me. She showed me how to create my own realm, a realm of the word, without owning any terrain myself. For women like us, who are working, her example still inspires: we go out and own what we own, but when we come back to our children and tell them our stories, we teach them how to possess themselves, however they choose to later take on the world.

I remember being five and hearing about the women burning their bras. I remember this movement. And I remember my mother watching from the sidelines, quiet, as the minister's wife who'd given up her literary career. She had missed that generation. Unless she was willing to give up everything, she couldn't find a place within feminism. It would have been too much to ask her to abandon her life. At the end of the day she really loved my father and her family more than she wanted a career. Yet as the years went on I could see in her a burning, a desire that could not be fulfilled as long as she held the mother role the way women had to at that time.

As a minister's wife, my mother did do something similar to what I do as an artist. When she met somebody walking through that receiving line in church, she would portray what that person wanted to see. This had nothing to do with who Mary Ellen Copeland was. She read a lot of literature and began to become other pieces, reflecting back what that particular person needed to see in a minister's wife.

The conflict I sensed in my mother was one reason I was willing to go on the artistic and spiritual search that became my life for so long. I got drawn in as a really young child, Tash's age, when I was starting to spend all my time on the piano. There was something brewing in me, drawing me to the Magdalene, never the Mother Mary, which is unfortunate. I became more drawn to the mother aspect later.

Waiting to have children is a risk, as I discovered, but there are good reasons to do it. Medical science is trying to catch up with the changes that the feminist movement helped make for us. Our bodies haven't quite caught up yet to help us achieve that. Mentally and responsibility-wise, many of us aren't ready to be mothers and put somebody else first at twenty-five, because in our society we're taught to find out who we are first. I know a lot of twenty-five-year-olds who are not ready to put another Being first. Talk to Chelsea. When she's here with Natashya and me, sometimes she'll just say, “I can't believe how much a child needs.” And I say, “Chels, I can't believe how selfish we can be.” But we're just in different places right now.

ANN:

Amos was finally ready to enter motherhood in her early thirties. She felt strong in her music, and her soul connection with Mark Hawley had begun. Like so many female high achievers, she thought she would accomplish this next goal as confidently as she had so many others. She soon discovered that the goddess guide who walks you through life's passages might not be the one you d hoped you'd meet.

Not long before my first miscarriage in 1996, I had my chart done by mythic astrologer Wendy Ashley. I'd had my chart done many times, but I was beginning to figure out who the charlatans were versus the credible people, and this woman is at the top of her field. It's not like you're dialing 1-800-PSYCHIC; this woman studied mythology under Joseph Campbell. I was beginning to see myth in my life.

I didn't want my myth, the one the charts revealed to me. This was when I was making

Pele

, Mark and I were together, and I thought I might be pregnant. I had this first reading and was given the Rhiannon myth. Rhiannon was a Welsh queen who lost her child under horrible circumstances: he was kidnapped and her subjects accused her of not only killing him but also eating him alive. She was then forced to serve penance within the court for seven years, until her son finally returned.

I didn't want to know about that. Are you kidding? Who wants to hear that? I was not even concerned about the other meanings of Rhiannon in popular culture, the fairy thing, the fact that Stevie Nicks had claimed her in a song—I simply did not want to hear that I could even possibly lose a child. I was sitting there, saying,

Wait a minute, where's Dionysus, where's Sekhmet? I cant believe this.

It was a bitter pill to swallow.

Really, at first, I couldn't take it. I said,

That's not going to happen to me.

And of course it didn't happen just once—it happened three times. But I think I was missing the importance of the archetype. What mattered wasn't that Rhiannon lost Pryderi, her son, or even that she was accused of destroying him. What I needed to notice was her willingness to serve, for seven years, when people had accused her. It's a story of survival with dignity, and concentration on work rather than on your own ego. During this time, when I was having so much trouble carrying a child, and also going into dark places in my music with

Pele

and

Choirgirl

, I really needed to have Rhiannon's guiding spirit to help me make it through.

Because I have a lot of songs in my life that come with archetypes intrinsic to their own myths, I feel as if I've been able to try on many different archetypes. So much so that it feels like a Pandora's box of archetypes sometimes. But not all of them figure in to my personal myths. Of course, they do when I step into the jeans of a song and take on that archetype in performance, whether in the studio or onstage. But I had to separate archetypes that I play with and that, yes, may affect me but are not foundational in my personal myth. Just as I had to accept Rhiannon as one of the pieces that make up my core person, I also had to realize that I am more aligned with Demeter than with Aphrodite, or even Persephone, who seemed like an archetype that I could claim. Even though there is a violation and a rape involved in my life, that story isn't my core. For example, Persephone is Beenie's myth. (Beenie is Nancy Shanks, one of my closest friends. We've developed the habit of calling each other “Beenie,” stemming from the expression “Do you know what I mean, bean?”) Beenie has been not only a best friend, but at times the nurturing force in our friendship. At other times, I've been the nurturer. Beenie was molested by her father from the age of two through the age of seven, a nightmare that recalls the rape of Persephone and the betrayal by Persephone's father, Zeus, and her entire life has been devoted to healing the deepest, most invasive unseeable scar that one can ever have. She has truly made a journey through the depths—the madness of bipolar anxiety disorder, which now is still a day-to-day struggle. But by making her wound her wise wound, she has transmuted her multiple rapes and betrayals into a fabric that is a piece in the rich tapestry of

Persephone, Queen of the Underworld. Beenie is no longer only the ravished, victimized Kore (Greek for “maiden”). Together Demeter and Persephone are maiden, mother, and crone.