Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (42 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

The ringmaster of Bozo’s Circus was called “Mr. Ned” on the show, and I heard too that he had once said something about “keeping the little bastards quiet” on the show.

N

arrator: One lesson an announcer learns is to make sure he is off the air before he makes any private comments. But even the greatest sometimes slip. A legend is Uncle Don’s remark after he had closed his famous children’s program. Let’s turn back the clock

Uncle Don: [Sung] “Good night little friends good night.”

[Spoken] “Tune in again tomorrow at this same time and I’ll be back with all my little friends. We’re off? I guess that’ll hold the little bastards for tonight.”

The Bozo report came in a 1986 letter from Jack Bales, reference librarian at Mary Washington College in Fredericksburg, Virginia. The Uncle Don report is from the LP record

Pardon My Blooper

(Jubilee PMB-1, undated), one of a series issued by Kermit Schafer. There are countless variations of the Bozo story with the offending child saying, “Cram it!” “Shove it!” “Climb it!” and the like to the clown, or to “Bozo,” “Clownie,” etc. Sometimes the child is said to have made obscene gestures, asked a sexual riddle, or played a game involving carrying an egg in a spoon. Although many people claim to have been eyewitnesses to this incident, every Bozo the Clown spokesperson and every published source on the program and its offshoots denies the story, and nobody has ever produced a recording of any such incident. The “little bastards” story, although long associated with “Uncle Don,” actually circulated among broadcasters concerning various other radio characters before Howard Rice (who changed his name to Don Carney) had assumed the “Uncle Don” persona for his popular radio show that ran from the mid-1920s until the late 1940s. Carney consistently denied the story, as do all serious histories of American broadcasting. In an essay included in my book

The Truth Never Stands in the Way of a Good Story

of alleged actual recorded or transcribed reports of the Uncle Don incident issued by the “Blooper” industry. These reports differ in several details, and none can be accepted as original or authentic. The sound quality of the recordings is superior to that of early radio broadcasts, very few of which were recorded anyway. The phrase “A legend is…” used in introducing these blooper reports suggests that the producers regarded the story as doubtful. Some have claimed that Schafer was merely “re-creating” an actual incident, but it is hard to see how one may re-create something that most likely never happened. Nevertheless, the story in all its variations does nicely illustrate how human nature will presumably cause someone to respond in frustration with an inappropriate off-color remark.

“Take My Tickets, Please!”

W

e’ve had a lousy football team here at…for the last few years. How bad? This story has been circulating:

This guy had tickets to the next game, but the team had been so terrible that he didn’t really want to go. So on a Saturday he went over to the mall to go shopping instead.

Then he got to thinking that he didn’t want the tickets to go to waste, so he came up with the clever idea to just put the tickets on the dashboard and leave the window down, inviting someone to steal them.

When he came back to his car he discovered that someone had put four more tickets to the game on his dash.

Sent to me in 1989 by a reader in the Midwest; I withhold further information to protect the feelings of the inept athletes alluded to. After I mentioned this story in a newspaper column, I heard from readers in other parts of the country who said that the same story was told there.

“The Dishonest Note”

I

heard this story in Pittsburgh around 1983, and I believed it was true until last February when my father-in-law told me the same story, swearing it had been witnessed by a buddy of his in Buffalo a few months ago.

There were a lot of cars in a small parking lot in Shadyside, a Pittsburgh suburb. A college-age guy came out of a store and jumped into his car, and as he backed out of the parking space, the bumper of his car caught the passenger side of the next car. He scraped the entire length of the other car.

He got out of his car to survey the damage. His car seemed fine, but the other one was a mess. Several passers-by witnessed the whole scene, as the college student pulled a piece of paper and a pencil from his car. They watched him write a note, stick it under the windshield wiper of the damaged car, and drive away.

When the owner of the damaged car arrived, he freaked out at the state of his new car. Then he grabbed the note on the windshield, and found that it read, “Everyone watching me thinks I’m leaving you my name and insurance information—but I’m not. Ha ha!”

Sent to me in April 1990 by Aurlie McCrea of Redondo Beach, California. Herb Caen, columnist for the

San Francisco Chronicle,

published a version of this legend in 1963, mentioning another from the

London Daily Mirror;

Caen published it once again in a 1971 column. A variation appears in an “Andy Capp” cartoon from 1973. “The Dishonest Note” is not only a

story

that reveals human nature, but the prank has actually been enacted by guilty motorists. A number of people have written to me confessing that they themselves wrote such a note, or knew someone personally who did. Others wrote to say that they found such a note on their damaged car.

“Pass It On”

I

n a high school class back in the ’60s, a narcotics officer from the local police department was brought in to lecture the students on the dangers of drugs. As part of his presentation, the officer brought along two joints from the evidence room which he placed on a tray to show the students.

“These,” he said, “are marijuana cigarettes, and I’m going to pass them around the room so you can see and smell them and know what they are like. When this tray comes back, there better still be two joints on it!”

The officer started the tray passing around the room, and when it came back to him there were

three

joints on it.

A widely told story that some tellers claim to have witnessed firsthand. Certainly any officer who tried such a ploy would be asking for it, considering the wit and nerve of some students and the ready availability of marijuana in many schools. Other versions describe a teacher discussing birth control and passing around a couple of condoms. This legend, like several others in this category, deals with a minor infraction; it depicts more of a prank than a crime. The next story is an obvious variation of “Pass It On,” but it involves higher stakes.

“The Lottery Ticket”

S

o this guy is a Colorado lottery winner—several thousand dollars—and he’s bragging about it to a bunch of people crowded around a table in a bar and grill. Someone doubts his windfall and says “Let’s see the ticket.” He pulls it out, and it is passed from hand to hand, finally returning to him. Except that the ticket he gets back has a different number than the one he handed out.

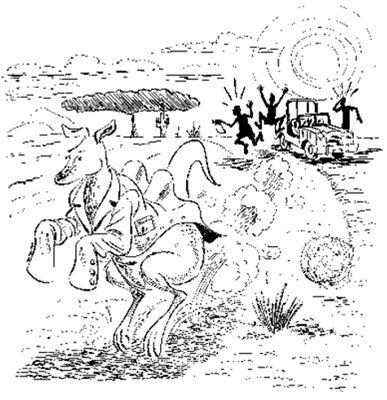

© 1998 Hilary Barta

From Jack Kisling’s column “Urban Legends Never Die” in the

Denver Post,

May 31, 1988. Kisling commented, “Whether an urban legend is literally true isn’t as important as whether it is true to life.” This update of the “Pass It On” legend quoted above has emerged in just about every state that has established its own lottery in the past few years, although both are probably just variations of an even older legend about a winning racetrack ticket being passed around a bar. Another lottery legend reported from diverse places describes a winner rushing out to his car (or to buy a new sports car) in which he will race to the state capital to collect his winnings; but he is killed in a car crash en route. In a recent popular story a man is fooled by his friends into thinking he has won a huge lottery payoff; after the man has kicked out his wife, moved in with his girlfriend, and charged expensive gifts on his credit cards, he learns of the hoax. Typically for urban legends, this last story has no follow-up saying what the man did next. A local lottery legend from Utah concerns the Mormon bishop who warned his flock not to participate in any form of gambling, including the lotteries run by surrounding states. Then the bishop has the good (or bad?) luck to win big on a lottery ticket he had impulsively bought in Idaho. When the Idaho lottery officials announced the winners, his name and picture were shown by all the newspapers and newscasts in the area.

“Dial 911 for Help”

P

eople also talk about the time that Mitchell expressed doubt about the 911 emergency phone system. Why? Because there is no 11 on the phone.

“It was a joke,” Mitchell says. But many delight in the notion that he wasn’t joking. Such is Mitchell’s reputation.

D

ear Heloise:

Thank you, thank you, thank you for telling parents that the emergency number is 911 and not 9-eleven. You wouldn’t believe how many people have said, “There is no 11 on my phone.”

Jokes by and about the short-term acting mayor of San Diego, California, Bill Mitchell, were included in a

Los Angeles Times

story sent to me about 1985 but without a specific date attached. The second example, from the “Hints from Heloise” column, was published on June 15, 1993; Abigail Van Buren had a longer version of the story in her “Dear Abby” column of March 3, 1990, and I have collected many other such accounts, the oldest in 1982. Some versions of the legend form of the story describe in detail horrible tragedies caused by people unable to find 11 on their telephones, but the worst such problem that any actual emergency service that I know of has been able to document was a momentary delay until the caller realized that the numbers to use were “one one” not “eleven.” Still, several local telephone emergency services have circulated memos reminding people to think of the series as nine-one-one, not nine-eleven. The ancestor of this story is a “Little Moron” joke from the 1940s, as summarized in a folktale index: “Fool answers phone late at night; caller asks, ‘Is this one-one-one-one?’—‘No this is eleven-eleven.’ Caller: ‘Sorry I got you up.’ ‘That’s all right; I had to get up to answer the phone anyway.’” I’ve also heard this legend transformed into an ethnic riddle-joke: “Did you hear why they had to get rid of 911 in Warsaw (Stockholm, Oslo, etc.)?”