Tommy Cooper: Always Leave Them Laughing (21 page)

Read Tommy Cooper: Always Leave Them Laughing Online

Authors: John Fisher

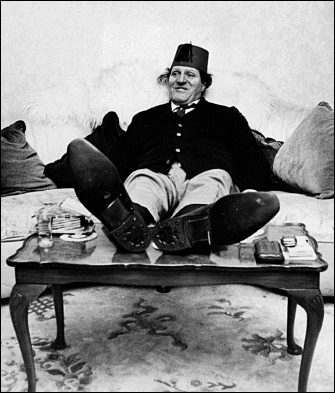

Time to relax with the famous feet up at home.

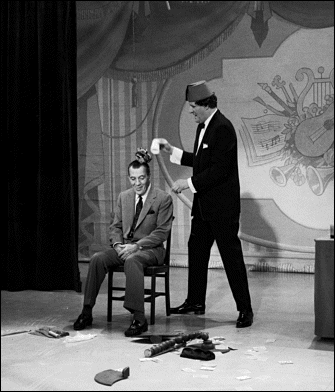

A sensation on the Ed Sullivan Show, New York, 1967.

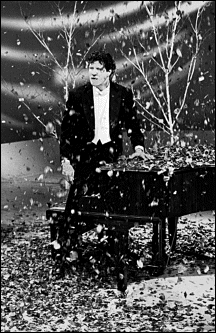

‘When autumn leaves start to fall …’

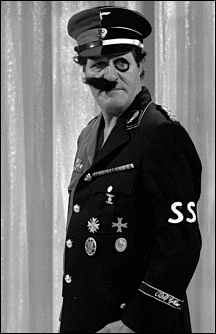

‘And ven zey are caught everyone vill be shot …’

Funny bones: with Anita Harris, promoting Tommy’s Palladium show, 1971.

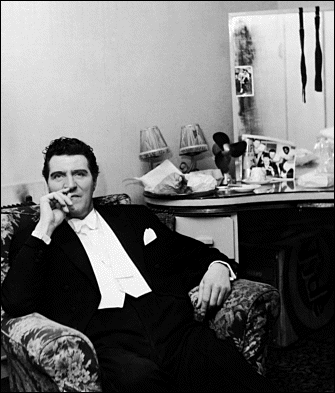

A rare private moment backstage.

aire, head waiter, chef, even the performers in the cabaret that included a Russian violinist and an adagio dancer. When Val asked Tommy whether he had had a chance to study the sketch, the reply was non-committal: ‘I haven’t had a chance to look at it yet.’ He thought no more of the matter until a few months later he was watching an episode of

The Tony

Hancock Show

, the early 1956 series for commercial television that featured the star before

Hancock’s

Half Hour

cemented his television reputation on the other channel. A carbon copy of the original sketch was played out before him. At one point he turned to his mother and said, ‘If the next character to come through the door is a Russian violinist, this has gone beyond coincidence.’ It was! As he says today, ‘I rest my case. I worried considerably about it. Thought I was going out of my mind. When I mentioned it to Tommy – I wasn’t aggressive – it was his defensive attitude that worried me. He was like Billy Bunter: “No, Skinner took the cakes.” It was nothing to do with him.’ Val, a modest and unassuming man, refused to have anything to do with Cooper for several months, but the need for a few shillings, the camaraderie of the magic profession and the fact that Tommy could be such good company brought them together again. But he remains quite clear about what happened: ‘He would have sold it. Thinking it was not suitable for himself in the first place, he didn’t want to give me any money for it and thought I would just dismiss it. If it was no good for him, it was no good for anybody. Did he seriously think he was brighter than me in that regard?’

John Muir also testifies to Tommy’s less than straightforward manner in dealing with scriptwriters when money was concerned. For one Blackpool summer season Muir provided him with a routine that burlesqued the skills of Percy Edwards, the well known animal impersonator. When he asked how it was working out, Tommy replied, ‘It died. Not a laugh. I tried

it out and had to drop it.’ That put paid to any suggestion of payment. However, when he mentioned the matter to another act on the bill it transpires it was getting huge laughs each night. A short while later John caught Cooper doing the routine on one of his television shows for Thames. When he approached the company they told him that Tommy had claimed the material as his own. The broadcaster smelled the proverbial rat and wasted no time in paying him. Andrews, Muir and Brad Ashton all testify to his cheeseparing habit of delaying the use of material submitted by them until he could perform it on television, thus shifting any financial obligation from himself to the production company. That he might continue to use such material in his stage performances in perpetuity was something that was always pushed to one side.

From a myriad of sources the Cooper comic repertoire slowly came together. In the early days his energy was indefatigable as he went out of his way to try out material that was new to him. David Berglas, Pat Page, and Bobby Bernard all share fond recall of him popping into meetings of the smaller London magic clubs, like the Thursday sessions of the Institute of Magicians in Clerkenwell and the Friday ones of the London Society of Magicians in Red Lion Square, to test new stuff

en

route

to a late night cabaret booking. At other times he would test gags by springing them on friends or family in anxious anticipation of the reaction. ‘Usually he bursts into the kitchen with a funny hat just as I’m putting the joint in the oven – and is hurt if I don’t laugh,’ Gwen once said. Jokes were like tricks, things to try out with renewed excitement whenever he found one to his liking. Backstage or at rehearsals he never lost an opportunity to try out a new gag, as Bob Monkhouse reminisced: ‘I once saw him in a dressing room dangling a bath tap on a piece of elastic. I asked him what he was doing. “It’sa gag,” he said. He was going to come on, dangle it up and

down a few times and then say to the audience, “Tap dance!” I thought the idea was terrible, the worst joke I’d ever heard. “Don’t do it,” I said. “They’ll attack you.” Of course he went ahead with it and brought the place down.’

The final arbiter always had to be Cooper. Once he had convinced himself that something was funny, there was no stopping him. One tires of the times ones sees his jokes dismissed as ‘old’. Billy Glason hit the nail on the head in his sales pitch: ‘

There are no old gags!

The only thing old about old gags are the ones who’ve heard them before and the answer to those who want to admit their age when they remark that a gag is old, is “Say, you don’t

look

that old!”’ Tommy once confided his feelings on the issue to magical friend, David Hemingway: ‘It doesn’t matter how old the gag is. It doesn’t matter how many times the audience has heard it before. If it’s funny, it’s funny.’ Anyhow, public memory is so short that what an audience is capable of forgetting is remarkable, until the point when familiarity does set in and a joke assumes the status of an old friend. Who would not have attended a Cooper show and come away disappointed at not hearing lines like these?

I said to the waiter, ‘This chicken I’ve got here’s cold.’ He said, ‘It should be. It’s been dead two weeks.’ I said, ‘Not only that, he’s got one leg shorter than the other.’ He said, ‘What do you want to do? Eat it or dance with it?’ I said ‘Forget the chicken. Give me a lobster.’ So he brought me a lobster. I looked at it. I said, ‘Just a minute. It’s only got one claw.’ He said, ‘It’s been in a fight.’ I said, ‘Give me the winner.’

When Davenport’s magic shop had its premises opposite the British Museum, the joke used to be that Tommy went to one for his tricks and the other for his gags. Barry Cryer has a

theory that Cooper was fully aware of the awful quality of much of his material and was entering into a conspiracy with his audience: ‘He knows it’s a terrible joke and he knows they know it’s terrible. They were laughing less at the joke itself than at how bad it was, not to mention his effrontery in sharing it with them.’ My contention is that there is no such thing as a bad gag, if it is well told and the personality of the teller can surpass its inherent triteness. That may amount to the same thing. Certainly, one of Cooper’s skills was his ability to spot what would work for him in this regard, to recognize the innate structure that would connect effortlessly with his delivery.

Someone once commented that the best Cooper one-liners had an almost haiku-like quality. I doubt if the theory would hold water if subjected to the many rules of this most compact, most complex literary form, but one senses what they were trying to say. No one understands the mechanics of the process better than current comedian, Tim Vine. Had he been around in Tommy’s time, providing the master with material, he would have been the one writer Cooper made sure he paid properly. Without impersonating or making any overt reference to his hero, Vine keeps alive the logical illogicality that underpinned so much in the Cooper joke compendium. Likewise had Tommy been alive today he may well have had a harder time on the circuits that Tim plays, since he could not claim to have been the comic auteur that modern audiences expect in such situations. In a curious twist of time warp, jokes by Vine published indiscriminately on the internet have been wrongly attributed to Cooper’s repertoire. When through a horrendous series of misunderstandings one of them found its way into my stage tribute,

Jus’ Like That!

it achieved as loud a laugh as any of the gags Cooper had told in his lifetime: