Tolstoy (75 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

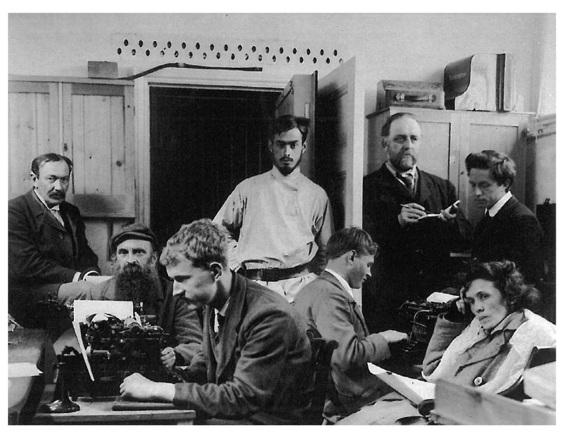

15. Employees of the Free Word Press in the vault at Chertkov's house in Christchurch, 1906. Evgeny Popov is seated second from left; Ludwig Perno, custodian of the Tolstoy archive, is seated at the typewriter on the right; and Chertkov's wife is seated in the foreground. Chertkov is standing behind the door.

A quarter of a century on from their first meeting, Chertkov's life was still characterised by his unswerving devotion to Tolstoy, and in 1908 he and his family took up permanent residence in a new house they built on land inherited by Tolstoy's youngest daughter Sasha at Telyatinki, three miles from Yasnaya Polyana. Shortly after Chertkov's return Tolstoy turned eighty. Such was the groundswell of support for him across the country that the Church felt compelled to issue a plea to all true believers to refrain from celebrating the occasion. It also tried to take Tolstoy to court for blasphemy against the holy personality of Jesus Christ, and arranged for icons to be painted which depicted him as a sinner burning in hell. Father Ioann, Tolstoy's implacable foe, even wrote a prayer requesting that he die soon, but it was Father Ioann who died in 1908, not Tolstoy.

178

The few dissenting voices were anyway drowned out by the well-wishers who far outnumbered them. Two thousand telegrams wishing Tolstoy many happy returns were delivered to Yasnaya Polyana on 28 August, and Charles Wright, librarian at the British Museum, arrived at Yasnaya Polyana with birthday greetings signed by 800 English writers, artists and public figures, including George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells and Edmund Gosse.

179

Tolstoy had halted the activities of a special celebratory committee established in January 1908, just as he received his first birthday present: a phonograph sent to him by Thomas Edison. There were thus no official undertakings, but that did not stop a flood of ecstatic articles appearing in the press. Journalists gushed that there had never been a cultural celebration in Russia like it ever before, and that while the Pushkin Statue festivities had captured the national imagination back in 1880, this was an event on an international scale. Merezhkovsky proclaimed the Tolstoy celebration as a 'celebration of the Russian revolution', and declared that Tolstoy had against his will 'turned out to be the radiant focal point of Russian freedom'.

180

'Lev Nikolayevich' had long been a household name in Russia, and it had become quite common to overhear passengers on a train discussing him as if he were a close acquaintance. The labels accompanying the photographic chronology in the special supplement published by the newspaper

Russian Word

to mark Tolstoy's eightieth birthday said it all - from the earliest photographs, labelled 'Count L. N. Tolstoy' when he was an unknown author, to 'Lev Tolstoy', and finally the familiar 'Lev Nikolayevich'. There were only a few notes of criticism amongst the scores of birthday tributes published, and one of them was by Lenin, whose first and most famous article about Tolstoy, 'Lev Tolstoy as a Mirror of the Russian Revolution' appeared in

The Proletarian.

While praising his attacks on the tsarist regime, Lenin not surprisingly condemned Tolstoy's philosophy of non-violence which he held responsible for the failure of the 1905 Revolution.

In addition to all the greetings cards and telegrams, Tolstoy received gifts, some of which were rather ill-judged, such as the several thousand cigars in boxes with his picture on the front.

181

Having Chertkov living so near to him was undoubtedly the best birthday present as far as Tolstoy was concerned. The Chertkovs and all the local Tolstoyans, such as Maria Alexandrovna Schmidt and Ivan Gorbunov-Posadov, were invited to a festive dinner at Yasnaya Polyana along with family members, friends and relatives. It was the first and last such occasion, as in 1909 Sonya started to become increasingly paranoid, and also increasingly hostile to Chertkov. The battle with him revolved around Tolstoy's will and his late diaries. She was as obsessive as Chertkov about her husband's legacy, but not as powerful as he was. Much as it was rewarding to enter into correspondence with figures like Gandhi in 1909, and exciting to be filmed by some of Edison's colleagues, Tolstoy's desire to become a homeless wanderer became more and more intense.

In March 1909 Chertkov was ordered to leave Tula province. Politics and personnel had changed in St Petersburg, and suddenly he no longer had so many friends at court. Tolstoy was mortified, and even Sonya wrote to protest, but the Chertkovs were obliged to move from their new home. They took up residence at Vasily Pashkov's old estate Krekshino, about twenty miles outside Moscow. As the year went by, relations between Tolstoy and Sonya now sharply deteriorated. First she found the manuscript of Tolstoy's unpublished story 'The Devil', about a young nobleman's passion for a peasant girl, which opened up a lot of old wounds. Then, in July, she discovered that the power of attorney Tolstoy had given her to manage his property in 1883 did not give her any legal rights to them.

182

She was livid. During Tolstoy's illness in the Crimea, Masha had managed to procure her father's signature on a will which relinquished the copyright on all his works. Sonya had managed to reinstate her name as a beneficiary back then, wanting to ensure that her children and not publishers would benefit from royalties after her husband's death. Tolstoy, however, had other ideas, of course, and Chertkov fully supported his desire to waive all rights over his works. Sonya also faced a new problem as there was a new Tolstoyan in the midst of her family: her daughter Sasha, who had long resented her mother. Sasha turned twenty-five in 1909, and she now devoted herself to working for her father, and with Chertkov.

She was determined to thwart her mother, and make sure a will was drawn up which denied her any rights to her father's works.

Tolstoy had been tipped for one of the recently introduced Nobel Prizes several times, and had published a letter in the

Stockholm Tageblatt

in 1897 suggesting the Dukhobors were more deserving recipients of the prize money, but the Swedish Academy had been repeatedly frightened off by his 'anarchism'.

183

In 1909, through the agency of Chertkov, he was invited to the Stockholm Peace Congress. Sonya suspected her husband was going to meet Chertkov behind her back and threatened to poison herself.

184

Tolstoy finally agreed not to go, and then in August the Congress was cancelled anyway. It was just at this time that Gusev was arrested for a second time, which was a further blow.

185

This time he was exiled to the Urals for two years. Chertkov began the search for a new secretary.

In September, Tolstoy went to visit Chertkov, stopping off on the way in Moscow, where he had not been for eight years. Before he left Krekshino towards the end of the month, he drew up a will handing over all his works written after 1881 into the public domain, and the manuscripts to Chertkov. A huge crowd gave him an ovation at the Kursk station as he set off back home to Yasnaya Polyana. He would never see Moscow again. In January Valentin Bulgakov, a young philosophy student originally from Siberia, arrived to become Tolstoy's new secretary. Like Gusev, he was instructed by Chertkov to take copious notes on Tolstoy's day-to-day life. He thus became witness to the worst few months in the Tolstoys' marriage, and after her husband's death it was to Bulgakov that Sonya confirmed what the root cause of all the problems had been. In a letter of June 1911 she told him that she could not tolerate being supplanted in her husband's affections by Chertkov. She had spent forty-eight years being married to Tolstoy, as the most important person in his life, and now to have her husband tell her that Chertkov was the closest person to him was unbearable.

186

Sonya did not behave well in the last few months of Tolstoy's life, and numerous doctors correctly diagnosed paranoia and hysteria, but she was not mentally ill. She just felt out of control, usurped and desperate. She feared poverty, and she feared her name being blackened.

In June 1910, Tolstoy made another trip to visit Chertkov, and at the end of the month Chertkov was allowed to return to Telyatinki. Sonya now tried to stop her husband from seeing him, and when she discovered that Chertkov had his diaries from the last ten years, she demanded they be given to her, fearing they would expose her in a bad light. She felt she should have them, as her husband's rightful executor, but Tolstoy refused to accede to her demands. Finally, after bitter conflict, Tolstoy agreed to take back his latest diaries from Chertkov, in order to hand them to their daughter Tanya, who would deposit them in the Tula bank. Sonya and her husband had always read each other's diaries, but now Tolstoy began to keep a secret private journal. And in June he wrote another secret will, bequeathing the rights to his works to Sasha or, in the event of her death, to Tanya. Sonya was not made privy to its contents, but Tolstoy came to regret not having been open about it all.

Tolstoy was compelled to conduct his friendship with Chertkov by letter again, to avoid further hostilities with Sonya. In September she invited a priest to Yasnaya Polyana to conduct an exorcism to expel Chertkov's evil spirit. In late October, after discovering her rifling through his study, Tolstoy decided finally to leave. He had long yearned to leave home and set off on foot with nothing but the clothes on his back as a wanderer. In 1910 he finally did, leaving superstitiously at the age of 82 on 28 October in the middle of the night with Dr Makovicky, so he would not be pursued by Sonya. Despite his antagonistic relations with the Orthodox Church, it is entirely in keeping with Tolstoy's contradictory character that his first destination was the Optina Pustyn Monastery. Finding he was unable to receive spiritual guidance from the elders at Optina Pustyn, he visited his sister at her convent, then boarded a train heading south towards the Caucasus. As soon as she found out her husband had left, Sonya tried to drown herself in the pond.

Tolstoy never reached his destination. On 31 October he boarded a train heading south to Rostov-on-Don with Dr Makovicky and Sasha (who had joined them by this time), but had to get off at Astapovo when he fell ill. Tolstoy was put to bed in the station master's house. Sasha summoned Chertkov, who arrived with his secretary on 2 November, followed by Sergey, and then Sonya who had chartered a train with Tanya, Andrey and Misha. The next day Ilya arrived, as well as Gorbunov-Posadov and Goldenweiser, and on 5 November sixty army officers swelled the ranks of the secret police officers already stationed there. Once the news reached the press, the story made front page headlines. Soon the whole world knew what was happening at the remote railway station in Ryazan province. On 7 November 1910, amidst a frenzy of international publicity, which included regular headlines in

The

Times,

and the whirr of Pathé cameras, Tolstoy finally passed away. Sonya was allowed to see her husband only after he had lost consciousness. There was no reconciliation with the Church. By this time it was only too aware of the public relations disaster it had brought upon itself through the excommunication, but its increasingly frantic attempts to effect a deathbed recantation were an abject failure. Father Varsonofy came down from Optina Pustyn, but Sasha refused him access to her father, which she later felt bitter remorse about when she herself later came back to the Church. Tolstoy was not given Extreme Unction, and was buried very quickly, on 9 November.

There was only one place Tolstoy could be buried, and that was in the grounds of his ancestral home Yasnaya Polyana, where he had spent some seventy of his eighty years. He was interred exactly where he had wished, at the spot in the woods a short walk from his house where the little green stick was buried - the little green stick on which his brother Nikolay had told him the secret to human happiness was written. Aware that mourners from all over Russia would want to attend the funeral, and that the quicker the burial, the fewer would have time to make the journey, the Russian government made haste with the arrangements. There were so many students attending the meetings organised at Moscow University the day following Tolstoy's death that even the corridors were full, and the 800 reserved seats on the train that their representatives managed to negotiate with the management of the Kursk station could have been filled many times over. Thousands besieged the station, but the government forbade the running of any extra trains. Nevertheless, thousands did manage to pay their last respects, having sat all night on a freezing train which brought them to Zaseka station (as Yasenki had been renamed) in the early hours of the morning. It was a clear November night, bonfires were burning, and students had to struggle to restrain the enormous crowd awaiting the arrival of the special train bearing Tolstoy's coffin. But as soon as the train's yellow lights emerged out of the fog on that cold morning, the crowd fell completely silent.