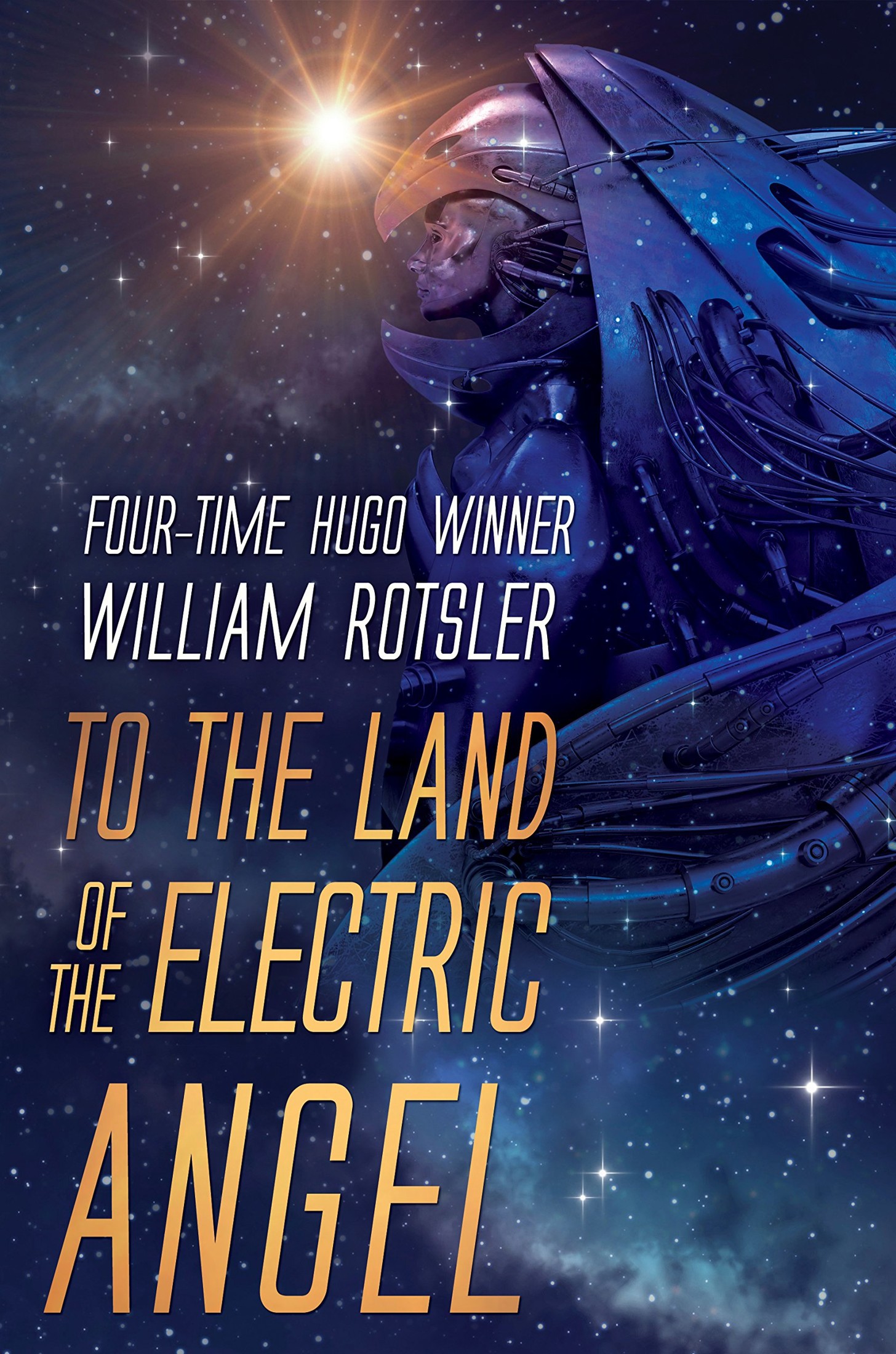

To THE LAND OF THE ELECTRIC ANGEL: Hugo and Nebula Award Finalist Author (The Frontiers Saga)

Authors: William Rotsler

Tags: #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Adventure

THE FRONTIERS SAGA

TO THE LAND OF THE ELECTRIC ANGEL

William Rotsler

Strange Particle Press

Digital Parchment Services

2016

isbn etc

For

Sharman DiVono with

love

CONTENTS

The walls shimmered and changed colors in a flowing, liquid way, reacting to Blake Mason's body heat as he strode through the entrance hall of his office. The dark-haired young receptionist smiled when she saw him, held out a sheaf of messages, and murmured a good morning.

Blake slowed and flipped through the messages. "Call Mrs. Templeton and tell her the Coe sensatron is ready for installation. Tell Caleb I want the terraces on the Castlekeep job ready for the tile setters by Thursday. Ask Count Radovsky if we could have lunch on Tuesday instead."

"Yes, sir. Aaron would like to see you, if you have time."

Blake nodded absently, then stopped to look around the entrance hall. "Tell. Libby to start some prelims on a new shocker hall. This one has been around four or five months. If I'm getting tired of it, the clients must be, too. Tell her ... um ... maybe something in the Martian Splendor style ... or Mirrormaze – even authentic Early 20th, if Dutch can find the pieces." Blake looked at the Bodycomfort furniture, custom-built items that had been used for two successive decors. "Ask Dutch to sell these with reasonable return, will you?"

"Yes, Mr. Mason."

Blake went through the big dilator door, less a functional port than a bit of showmanship intended to impress the clients of his decorating and design company. He turned right, and went down a hall to the work area.

"Environmental Concepts" was a small company working with big clients and big concepts. Blake did not just decorate a house, he investigated the life-style of his clients, conducted exhaustive interviews, made tests, and then designed the house or condominium, the grounds, the furniture, and sometimes even whole wardrobes. Some of his projects were not for individuals but for corporations, for public use, or for specialized use by select individuals. The hallmark of Blake's success had always been the solid background and firm foundation upon which he used the genius of his talent and intuition.

His company required space and the workroom was big. The one he entered, one of three on this floor, was filled with drawing tables, sturdy worktables, finished and unfinished scale models, sketches, photographs, holograms, books of sample material, reference volumes, and several people.

"Hi, boss," Carole said, looking up from her table. Blake stopped and looked over her shoulder. "It's the Alice-in-Wonderland thing for Alexander," she said.

Blake nodded, and pointed a finger at the Cheshire cat on a big mushroom. "Hologram?" Carole nodded. "That will work, fading away to just a grin. The rest is pretty much animatronics, isn't it?"

"Yes, the cards are going to have to be about four millimeters thicker than Caleb first thought. So much wiring has to go in, that they will be somewhat thick playing cards."

"That's all right, the effect will be good." He touched Carole on the shoulder and she looked up at him. "Everything all right between you and Mark?"

She smiled and patted his hand. "Yes, we talked it all out. I suppose he's just more monogamous than I am. It's all right, really."

"Okay," Blake said with a smile. "But if I can help..."

"Not unless you can bring Mark up to the twenty-first century."

"My time machine is in the repair shop. The sand was running out of the bottom."

"Too bad." They smiled at each other, and Blake walked down the aisle between the rows of worktables, nodding and saying good morning to those who looked up.

He passed through the door into the center work area, a big high-ceilinged room where the large portables were constructed. Blake walked through the chit-ter and casual disarray that has characterized artists' studios since the dawn of time, but he wasn't seeing it. His attention was caught by Aaron and the big column of whitish plastic on a shiny black base.

The slim young man straightened up from a drawing board, and a worried smile replaced a worried frown.

"God,

I'm glad you're here! Look at

this!

Dawson gave me those specs for the Mohawk job, but they simply don't match the prelims.

They

want the color fountain

here,

and and Dawson has it

here.

Now, this is where you wanted the Hayworth construction, wasn't it?"

Blake looked away from the tall white cylinder and peered at the workprints. "I think he's reversed the coding. See?" he said. "Phone him and have Dawson check. Mohawk wants this whole job done by the end of July, for the opening of the Emperor Nero Arena. They are starting a PR blitz about how the Greeks and Romans tinted their statuary with lifelike colors, so all this will work in very well."

Aaron brushed back a lock of unruly hair. "Oh, I know, but after several thousand years of looking at those bleached statues, going back to fully painted ones seems positively

gauche,

really, like something that bitch Georgina Sand would do."

Blake smiled. "Ah, love unrequited." Aaron shifted some papers and made a loud sniff. "Did the molecule skimmer arrive?" Blake asked.

"Yes. Mario tested it down at the studio and it worked

fine.

It has fine and wide band adjustments and you can sculpt even high-tensile plastiment with it. It will be

marvelous

for shaping the rocks around the Shah's summer home. Looks so

natural,

just like weathering, except for the patina, of course. No chisel marks, no laser burns, just

marvelous!"

Blake pointed at the column of white plastic. "Is Nimma finished with this fleshmolder yet?"

"Yes, I think so. Here, let me. Carl showed me the setting for the

loveliest

configuration. Watch."

Aaron punched out a code on the small ten-digit control panel on the far side. Slowly the cylinder began to writhe with a rather sinuous movement as the memory plastic reshaped itself, shifting its colors, until it was a replica of Michelangelo's

David,

slightly blurred and indefinite, as if seen through water. But the color and texture were human flesh.

"See?" Aaron said delightedly.

"Look

how be reformed the genitalia!"

Blake looked stonily at the plastic statue and asked, "Has he worked anything else out?"

"You don't like it?" Aaron asked anxiously.

"I've seen the original. I didn't think it needed any improvements."

"Well,

Blake, really, he was just using this as a

test case,

something to judge against. Don't fret at him,

please. Libby

made the suggestion that he copy a few of the

classic

pieces to get a feel of the thing."

Blake nodded. "Okay, what else?"

Aaron hopped over to Carl's table, rummaged around, and came up with a code card. He bent over and punched out another code. The

David

blurred and melted as the plastic reformed into another human shape, this one the

Venus de Milo.

Carl had added the broken and lost arms, mimicking the placid postures of the period. The sculpture held for ten seconds, then once again writhed, and darkened from ivory to deep red as it shaped itself into the so-called

Colossus of Mars – the

strange, weatherworn, shrouded figure of indefinite species. It might even have been a humanoid with folded wings, but it was too worn to tell.

"Stop it," Blake said, and Aaron punched a hold. "This is where his waterworn look works. Have him try some abstracts. That effect should be exploited, because it is very good."

"Yes, of

course,

Blake, I'll tell him when he gets in. He's over at General Electronics, trying to get the new M-9 cilli nets for the casino sensatrons. They're getting terribly difficult to get these days.

Everyone

is doing sensatrons now."

Blake nodded in agreement. Those complex engineering miracles – sensatrons – used ten- and twentythousand-line screens, a variation on the hologram, and a computer's ability to "paint" three dimensional subjects in what seemed to be three dimensions to Alpha-wave generators and subsonic projectors played almost directly upon your emotions. Most sensatron artists made continuous loop operations, designing the action to end up at the starting point and editing the tapes and control wafers to obscure any joining, making the "performance" continuous as long as there was power. The original cubes by the artists were often quite large – as much as two meters square or cubed – and some were over two meters high. They were always rectangular, due to the necessity for AE optical flatness of the screen surfaces to give the optimum apparent depth. Already, artists complained about the artificial restrictions of the cube shape, but so far neither artist nor engineer had figured out another way to achieve the same result.

"All right," Blake said to Aaron. "Check with Mohawk."

Aaron nodded

and

Blake went through the workrooms, and on into his own small area just past the massive freight elevator. His studio had high ceilings and strong, clear Easyeye light panels. Here he kept his own personal tools – virtually every one listed in the catalogs, plus a few he had designed or adapted himself – all carefully cased, stored, or hung. Next to a large drawing board was a shelf of thick portfolios that bulged with prelims and finished drawings for a hundred environments.

Next door, in his business office, things were arranged with less clutter. Models and photographs were displayed to impress his clients with both the achievements and the taste of "Blake Mason, Environmental Concepts." There were photographs of the Martian Civilization exhibit for the Madrid World's Fair, Shawna Hilton's house, the FSA Monument, the

Valhalla

dome, an elaborate fantasy for the opening of Caligula's Circus, and the interior of the astrobubble on Station One. Displayed with pride were tridees of Casa Corazon, forever lost in the Peruvian earthquake three years before. Most impressive, however, were the photographs and scale model of Blake's biggest commission: the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, which he designed for the Shah of Iran.

But here, in the studio, was his own private world. Few clients were permitted in, and few employees, either. Blake's business was providing environments of an unusual nature, whether reconstructions, fantasies, artistic tours de force, or merely trendy "in" designs that were kept for a season or two. Few of his customers wanted to know how he did his work. Either they didn't care, or else they actively avoided destroying their illusions by not going backstage, so to speak. Their usual questions were only "How much?" and "When will it be finished?" Blake always knew he had a really rich client when, in the best I. P. Morgan tradition, he was not asked, "How much?"

Blake had dozens of the varied tools he needed close at hand. These ranged from a simple, old-fashioned graphite pencil to sophisticated Alpha-wave projectors, from memory-plastic templates to his own coded sample books that listed everything from fabrics and metals to robotronic plug-ins, animatronic modules for constructing human, animal, and fantasy creatures, and Martian synthetics. He had a tieline to a Da Vinci Visual Computer, as well as a terminal that was used mostly for computer checks on material strengths, prices, availability, and delivery dates. But Blake's most used, and perhaps most important, tools were the pen and paper with which he roughed out ideas. With these he put his thoughts down to find direction and to hold on to parts of a concept while he thought about its other parts.

Blake stopped and looked at the big project that sprawled across a large, flat worktable. It was a multilevel, a complex harem he was designing for a famous publisher. When completed, the structure would have big orgy rooms, carpeted, cushioned, and filled with rich textures set off by soft lighting. There would also be intimate cul-de-sacs, decorated with rich fabrics, and sensuous furniture that writhed in a seemingly endless mariner through the four acres of the arcolog penthouse. To the untrained eye the model was a confusing mess, with penciled notes on scale walls, bits of fabric or color taped to walls and floor, temporary partitions stapled into position. One level was raised with a paperbound copy of

The Famine Years,

and another with a heavy book entitled

The History of the Modern Roman Games.

One could see where arches and terminals had been drawn, then eliminated with a slash of ink. Conversation pits and ceiling-television panels were sketched in, cases for old-fashioned books noted, an enlargement of the kitchen area indicated with scrawled arrows, a photo of a sensatron pinned into a corner. The mock-up was now only a tool, a sketch that when finished would be given to a talented subcontractor for translation into a breathtaking scale model that would be photographically realistic, complete with tiny art objects and a few human figurines for visual scale.

Why do they come to me for these blatantly sexual environments?

Blake asked himself.

Commission after commission is for something boldly sensual. Perhaps no more than 15 or 20 percent of my work is for a design without a sensual overtone. The Africaine job. The Alice-in-Wonderland project. The eighteenth-century house for Karsh.

Can what Jacques Chariot said be true?

Blake asked himself ... Standing there before the hologram stage – much as Oscar Wilde might have stood before an Adam mantel – Chariot, a mauve-tinted man in his hand, dropped his acid pronouncements with his famous studied casualness. "Mason is popular, Lady Faring, because he funds sex dirty. He makes his environments so deliciously sensual for all the

wrong

reasons."