To Reach the Clouds (10 page)

Read To Reach the Clouds Online

Authors: Philippe Petit

Night has fallen when, by luck, JP finds a parking place just in front of 422 West 22nd Street and wakes me up with a sonorous “We're back!”

Â

I cannot believe my sleepy eyes: Jean-Louis is on the front stoop, trying to roll the enormous coil of the cable up the stairs all by himself.

An expert glance informs me the cable has been magnificently cleaned.

I ask Jean-Louis why Mark and Paul are not helping.

“The Australians?” answers my friend with disgust. “You have no idea! We spent the day bickering.” And he explains how, after I left with JP for Boston, they refused to do anything, insisting they could do nothing without my approval. They barely agreed to keep an eye on the cable drying in the street while Jean-Louis took over their job, that of getting the missing tools.

“Imagine me, looking all over the city for stores that sell tools, not even knowing how it's called in English! Now I know, it's called â

arrd-wear-storr

'!” By then it was closing time, and when Jean-Louis got back to the house exhausted and found Paul and Mark on the steps trading jokes, he got mad. “I told them we had to get together and prepare as much of the stuff as possible so that we could do the coup tomorrow. I told them I could not stay an extra day. I saidâall this in my bad English, imagine!âI said if the coup does not happen tomorrow, it will not happen at all. And you know what this twisted Paul comes up with? He tells me that you and he have to have a talk, that your security is at stake, he's not willing to encourage a suicide, things like that. While I'm killing myself to finish cleaning the cable and roll it, all alone! They really have no guts, those two! Go talk to them. Maybe you can squeeze a little something out of them. But to me it's hopeless.”

arrd-wear-storr

'!” By then it was closing time, and when Jean-Louis got back to the house exhausted and found Paul and Mark on the steps trading jokes, he got mad. “I told them we had to get together and prepare as much of the stuff as possible so that we could do the coup tomorrow. I told them I could not stay an extra day. I saidâall this in my bad English, imagine!âI said if the coup does not happen tomorrow, it will not happen at all. And you know what this twisted Paul comes up with? He tells me that you and he have to have a talk, that your security is at stake, he's not willing to encourage a suicide, things like that. While I'm killing myself to finish cleaning the cable and roll it, all alone! They really have no guts, those two! Go talk to them. Maybe you can squeeze a little something out of them. But to me it's hopeless.”

Â

I go talk.

Hiding my fury and lying through my teeth, I assure my Australian friends that I will be the first one to give up, if and when my safety or their security is at stake. I explain it's not too late to unite our efforts; we can work part of the night and be ready for JP when he brings the truck at eleven in the morning. I guarantee there's not much to it after that, just to hurry to the roof, maybe hiding a while and helping to pass the cable across.

Despair is a fine acting coach: Mark and Paul believe me. For a few hours they are back to work. But as the night stretches on, their confidence thins. By 2 a.m., they are demanding a forum.

“Give up!” I say, having no taste for talking to them.

The Australians give up. They abandon the coup. They go to sleep.

Â

Feverishly, Jean-Louis assists me in rolling, tying, making packages. Our plan is to work all night, finish in time for the 11 a.m. delivery, and hope that, after eight hours of sleep, our rested Australians will see that everything is ready and not have the heart to refuse to join us.

Dawn is spying on us from behind the window. The race against time seems futile.

A fever takes over my being; an extreme fatigue grounds me and grinds me into bits of intense despair. I have reached a point of no return on the road to disbelief. I am sure we won't be ready on time. We haven't even decided, Jean-Louis and I, the latest directives, once in the towers, once on the roof. The plan twirls and whirls inside my skull until the evidence escapes in drilling pain, as if during a trepanation: “We don't have a plan!”Bereft of all faith, yet awaiting a miracle, I continue to gather equipment and to pack, like some beheaded animal. All the while I focus an energy I no longer possess on keeping my eyelids open. I do not understand why my body does not fall asleep on the floor.

We are one cardboard box short.

Mechanically, Jean-Louis goes out into the early morning streets and comes back brandishing two large empty boxesâ“for you to choose”âstill dripping with dead fish and broken

eggs. He simply emptied the garbage they contained onto the sidewalk.

eggs. He simply emptied the garbage they contained onto the sidewalk.

We laugh at our madness.

I fill one stinking box to the rim as Jean-Louis catches his breath. But when we try to pick it up, the bottom gives out, spilling the contents all over the carpet. All of our boxes are much too heavy to move, and much too weak for their loads. And it is 7 a.m.

We should start all over again. This is dementia.

Â

Jean-Louis asks me what I think of the situation. In answer, I go into the bedroom and close the door. I collapse on the mattress, unable to keep tears of rage and exhaustion from burning my cheeks. But minutes later, I compose myself and calmly join Jean-Louis for an early morning chatâabout life, death, and the universeâuntil we decide it's not too early to tell JP the coup is a complete failure.

Is there another kind?

Seeing how devastated I am, Jean-Louis attempts to rebuild hope. He advises me to call everyone with the news that the coup has been postponed, instead of saying that it failed. He suggests I not throw the Australians out on the street yet. He promises to try to take a new leave of absence from his job in a few months, when I will have had a chance to reorganize the coup. He offers to accompany me to the airport to welcome Annie. He proposes that the three of us have dinner in Chinatown tonight â¦

It's still morning, and I have an idea.

Â

I wake Paul gently and ask him for a last favor: to call WTC and request a visit to the roof. He has bragged about a letter he's obtained from an eminent architect in London, recommending that Paul be allowed to visit and photograph the top of WTC to

complete his survey of high structures. I have the telephone number for a department other than public relations.

complete his survey of high structures. I have the telephone number for a department other than public relations.

Happy to feel needed and to diffuse yesterday's sourness, Paul calls immediately. When he hangs up, he announces that he has permission to conduct the survey this afternoon, and to bring a photographer.

Am I up to that? I know nothing about photography. What about picking up Annie?

Jean-Louis encourages me to go as the photographer. I'll be able to survey the roof in peace, I'll be able to take shots of what interests meâan extraordinary opportunity! He figures out everything, down to the bus schedule: he'll even lend me his expensive cameras. We'll ride together to the airport, and on the bus he'll give me a crash course in photography; he'll wait and pick up Annie while I ride back to Manhattan, arriving just in time for the survey appointment. “If we go now, you can make it!”

Despite mental distress and physical exhaustion, I attend carefully to Jean-Louis's crash course, and by the end of an hour-and-a-half bus ride, I am a photographer.

Â

“What a fine day,” says the architectural consultant as he gives Paul and me a tour of the deserted roof of the north tower. Indeed, the sun is warming the air, there is no wind, and even I calm down and enjoy the view.

Understanding that we have an agenda, our considerate guide offers to leave us alone for a while. He has some stationery with him and wishes to sit by the crane and write a letter while he works on his tan.

Freely and peacefully for the first time, I scout the roof. Paul walks around, keeping an eye on our guide.

I direct my cameras wherever I wish and take a number of priceless shots. I can inspect the locations where I'm considering anchoring the cable, comparing, studying, kneeling to appreciate a detail. It's paradise!

I'm about to arrive at a solution when Paul interrupts; he

judges we've been glued too long to the corner facing the south tower. “We've got to move! He's going to suspect something!”

judges we've been glued too long to the corner facing the south tower. “We've got to move! He's going to suspect something!”

Can't he see the consultant is absorbed in his letter?

Â

To get rid of Paul and to create a diversion, I send him circling the roof.

He returns a moment later and tells me he wants us to leave.

A violent, albeit hushed fight follows.

My anger does not dissipate Paul's growing anxiety. It's his time on the tower, it's his appointment, he says, and he decrees that we must go immediately. On the verge of panic, he breaks away and pulls the official from his writing, to tell him that we're finished with our survey.

Backing up toward the stairsâI want to snap one last pictureâI trip and fall into a nest of steel beams, smacking both of Jean-Louis's cameras.

Â

Back home, beat with fatigue and disgust, I kick the door open with my boot and throw myself into Annie's arms for a second, before pulling her into the bedroom and slamming the door.

Instead of asking about her flight, I pour on her all my rage and misery: I've been fighting nonstop with Jean-Louis, the Australians have given up, Paul is completely mad, I may have wrecked Jean-Louis's cameras. “And with all this, I couldn't even be at the airport for you!”

Annie braces me, and I go talk to Jean-Louis about his cameras. Although they are still operative, they will need repair. But when I offer to street-juggle to pay for it, Jean-Louis tells me not to worry, it's part of doing the coup.

Â

Then I return to Annie and resume my bitter narration of the past few weeks, concluding, torn and eviscerated, “You see, I can't count on anybody! The coup is impossible anyway!”

“So give up!” answers Annie, to my astonishment. “Until now, you've always attacked mountains, and you've always triumphed. But there are mountains that can't be conquered. Give up! You

were on the way to killing yourself. Or else by some miracle you'd do the walk and be a dot in the sky. No one would even see youâit would be almost ugly. Give up! Think of all the things you want to do. You could go back to Vary, put a high wire act together, be hired by Circus Sarrasani, and share the bill with Francis Brunn. You have so many dreams!”

were on the way to killing yourself. Or else by some miracle you'd do the walk and be a dot in the sky. No one would even see youâit would be almost ugly. Give up! Think of all the things you want to do. You could go back to Vary, put a high wire act together, be hired by Circus Sarrasani, and share the bill with Francis Brunn. You have so many dreams!”

Â

Jean-Louis succeeds in pulling us out of the house. We leave the Australians to their sulking guilt and run to Chinatown. Without asking my opinion, Jean-Louis buys three tickets for a Bruce Lee movie (knowing he's my favorite). After dinner, he breaks the fortune cookies, passing the slips of paper to Annie to read and rolling them into spitballs to shoot at me with his straw.

I try to smile and laugh with my friends.

I can't.

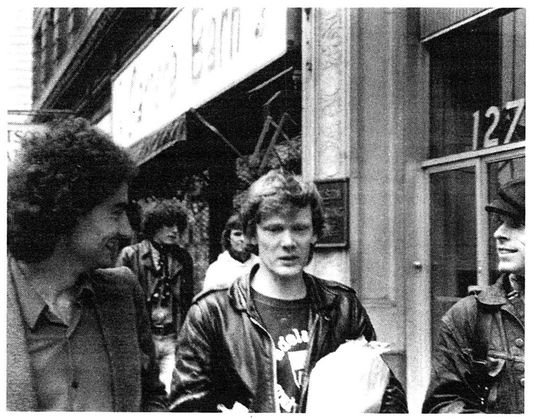

From left to right: Jean-Louis, Mark, Paul, Philippe and Jim

At 6 p.m. the next evening, Annie and Jean-Louis, obviously exhausted, stagger through the door and collapse on the sofa, laughing. They throw their shoes across the living room and stare at the ceiling for a second, then turn to me and exclaim at the same time, “Philippe, you're not going to believe it! But it's true, and we have the pictures to prove it!”

Â

In the morning, with hope and hopelessness still colliding in the air like drunken birds, I'd had nothing better to share with Jean-Louis than bitter regret: “It's a shame you're going back to Paris without even seeing what my towers look like!”

Answering his own curiosity and probably wanting to boost my morale, my friend decided to give it a try, and to bring his cameras “just in case.” I encouraged Annie to go as well: “You really should see how beautiful it is up there. Plus, a nice couple is the ideal guise to deflect suspicion.” It was my turn to give Jean-Louis a crash course: on how to sneak to the top. And off they went.

I stayed all day in front of the too-loud television to keep my brain from attempting to analyze my fresh disaster, and so I would not have to deal with the Australians, who glided by like ghosts.

Â

Now I'm dying to know the result of Annie and Jean-Louis's expedition.

Not sparing any details, they proudly retrace their race to the top of the south tower. They describe getting lost, being sent back down, trying all the elevators; they even mime their

moment de bravoure

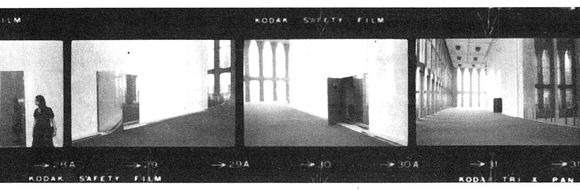

eluding a guard in the stairs. On the roof, Jean-Louis became exuberant. Forgetting his fear of the void, he went close to the edge and took some pictures. On his way down, all the way on his way down, he emphasizes, he kept taking picturesâpictures of each door Annie held open for him, each stairwell, each corridor, each dead endâuntil they found themselves safe and sound on the carpet of the mezzanine.

moment de bravoure

eluding a guard in the stairs. On the roof, Jean-Louis became exuberant. Forgetting his fear of the void, he went close to the edge and took some pictures. On his way down, all the way on his way down, he emphasizes, he kept taking picturesâpictures of each door Annie held open for him, each stairwell, each corridor, each dead endâuntil they found themselves safe and sound on the carpet of the mezzanine.

“I'll process them myself. You'll see!” promises Jean-Louis. “And you're quite right, it's fabulous up there!”

For the first time, my friend talks about the coup with zeal. For the first time, we discuss the past organization without rancor. For the first time, we joyfully build plans for the future. Jean-Louis turns his back to the Australians watching TV and concludes, “With a couple of really good guys, there's no way we can fail!”

I am already on the phone inviting Jim Moore to join our trio for a “last supper” in Chinatown. And this time it's I who shoot spitballs at Jean-Louis, as Annie and Jim try to keep score.

The next morning, Jean-Louis is gone.

The Australians leave soon thereafter. I find Paul's farewell gift on the coffee table: sketches of possible cavaletti configurations. I must confess, some of his concepts are brilliant.

I am left alone, with a taste of defeat on my tongue. I need to rest. I need to think. I need to bail out the sinking ship of my mind.

“You're not alone,” says Annie, who refuses to talk about WTC, advocates giving up, and will only visit the city she finds so dirty and dangerous if I'll come with her. Back in Paris she heard so many stories about New York's stray bullets and muggings, she won't even go by herself to the grocery store on Ninth Avenue.

Fine. I sleep two days straight. When I wake up, Annie is in the garden. Waiting for me to take her out, she has taken up a new

pastimeâfeeding the neighborhood cats. And these bold felines already have the nerve to consider the apartment their new home.

pastimeâfeeding the neighborhood cats. And these bold felines already have the nerve to consider the apartment their new home.

Great.

Let's go visit New York.

Other books

Andrea Pickens - [Lessons in Love 02] by Second Chances

I Kissed a Rogue (Covent Garden Cubs) by Shana Galen

The Mentor by Sebastian Stuart

How Like an Angel by Margaret Millar

Huntress by Taft, J L

Psicokillers by Juan Antonio Cebrián

I Remember You by Martin Edwards

Breaking News: An Autozombiography by N. J. Hallard

The Barbershop Seven by Douglas Lindsay

The Reckoning Stones: A Novel of Suspense by Laura DiSilverio