To Kingdom Come (23 page)

Authors: Robert J. Mrazek

Martin Andrews while interned in Switzerland, 1944.

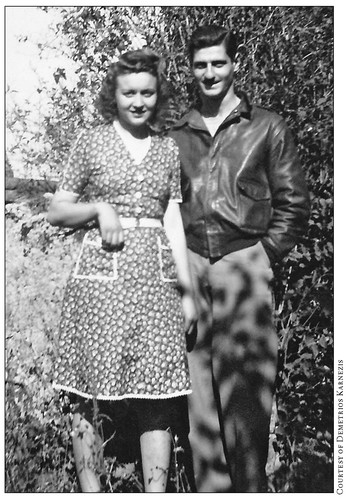

Demetrios Karnezis and Marie Therese Andre, France, 1943.

Robert Travis and William Calhoun shake hands after the Oschersleben mission, January 11, 1944.

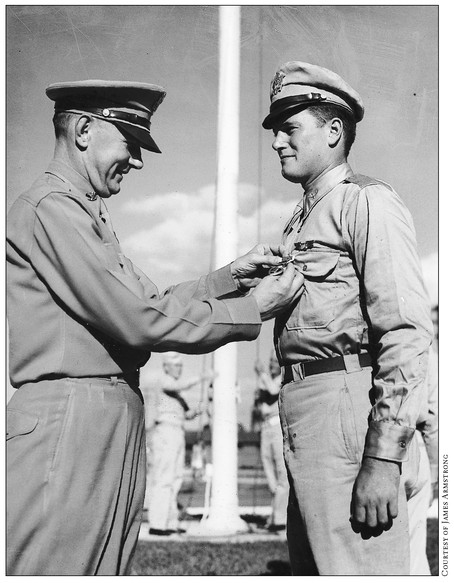

James Armstrong receives the Purple Heart, 1944.

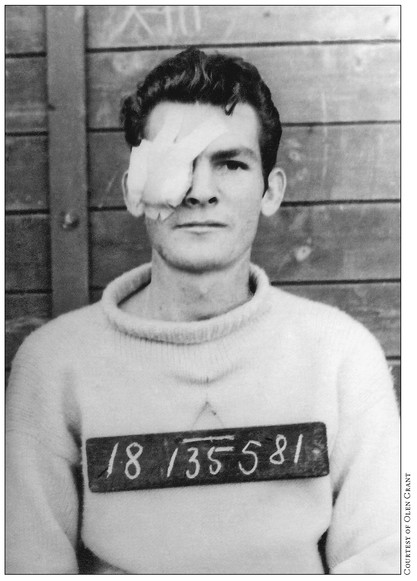

Olen Grant’s prison photograph, Stalag 17, Krems, Austria, 1944.

Remains of the Day

Monday, 6 September 1943

Grafton Underwood, England

384th Bomb Group

Colonel Budd Peaslee, Commanding

1330

A

ll their eyes were on the eastern sky as the scheduled time approached for the 384th’s return. Colonel Budd Peaslee stood on the railed widow’s walk at the top of the control tower and anxiously scanned the horizon through his binoculars. The scheduled arrival time came and went with no sign of the group’s eighteen Fortresses.

Budd Peaslee had commanded the 384th since its arrival in England back in June, and he had led many of the group’s toughest missions himself. He had agonized over the calamitous loss of half his original crews in July and August. He had watched good pilots crack up under the strain and tension of what they had gone through, and he privately wondered how long they could go on.

He considered the Stuttgart mission to be an important milestone. For the first time in the war, more than four hundred bombers had participated in a maximum-effort raid deep into Germany. Major Ray Ketelsen had led the mission, and he was an experienced combat leader. He would bring them back.

As the minutes passed with no sign of the group, Colonel Peaslee’s level of apprehension began to mount. The fuel factor had been calculated very carefully prior to the mission, and there was little margin for error.

A voice suddenly called out. Two planes were approaching the base. They were Fortresses. With growing shock, Colonel Peaslee realized they were the entire remnants of the 384th that were able to return to the base. Two out of eighteen. He watched the two B-17s land and rumble across the field to their hardstands.

Eighth Air Force Bomber Command

High Wycombe Abbey

Brigadier General Frederick Anderson, Jr., Commanding

1400

Fred Anderson was anxiously awaiting the first reports on the Stuttgart mission.

It was Hap Arnold’s last full day in England before flying back to Washington, and Anderson’s direct superior, Ira Eaker, was eager to deliver good news about the strike to General Arnold before his departure.

Across southern England, intelligence officers in each of the sixteen bomb groups were conducting postmission interrogations of the bomber crews. After each Fortress landed, the crews were sent straight from their hardstands to the briefing huts.

The intelligence officers were responsible for compiling an accurate account of each group’s performance, including how many tons of bombs were dropped on the intended targets, how many enemy fighters had been engaged and possibly destroyed, how intense the enemy flak had been along their flight path, and how many Fortresses and crews were lost or missing.

Fresh recollections were critical to gleaning the truth. Among other things, crew members often witnessed the last moments of other B-17s, which helped the intelligence branch determine where they had gone down, and if any parachutes had been seen.

Once the debriefings were completed, the information would be collated into a preliminary group summary, a “Flash Report,” and sent by Teletype to Eighth Air Force Bomber Command at High Wycombe, where it would be incorporated into a preliminary report being compiled for the entire attacking force.

Under the meticulously planned operational orders, all the bomb groups had been projected to return to their bases by 1330. Flash Reports were to be forwarded to High Wycombe by midafternoon.

For this mission, the information-gathering process was taking longer than expected, because scores of fuel-starved bombers had landed at other airfields after reaching England. They had to be refueled before the flight crews could return to their own installations and be debriefed.

This pushed back the timetable for General Anderson to complete his comprehensive report. He wouldn’t be able to provide General Eaker with a mission summary until late that afternoon or evening.

Entrépagny, France

384th Bomb Group

Yankee Raider

1400

A truckload of German troops arrived at the crash site of

Yankee Raider

within fifteen minutes of it slamming into the ground. The sugar beet field where it crashed was very close to a small French airfield now occupied by the Luftwaffe.

Accompanying the first German soldiers to the site was Robert Artaud, a fifteen-year-old French youth who was employed at the local hospital and drove its ancient ambulance. Along with many other villagers, he had seen the bomber circling overhead while under attack from the German fighters.

After watching it fall, he drove straight to the scene. Smoke was still billowing out of the front cabin

,

but the rear section of the aircraft, including the waist and tail, looked relatively undamaged.

The Germans had already found one dead crew member lying on the ground near the plane. He was wearing a parachute, but its rip cord had not been pulled. The man wore a wedding ring and his dog tags identified him as James H. Redwing. There was a bullet wound in his chest.

One of the soldiers climbed onto the wing and opened the storage bay in the fuselage where its life rafts were stored. He quickly retrieved the cartons of American cigarettes from their waterproof containers, while other soldiers looked through the cockpit windows for the pilot who had crash-landed the B-17.

Robert Artaud approached the right side of the aircraft with great trepidation, wondering if it might still explode. Through the open hatch, he saw a man in a leather flying suit lying inside.

When the aviator suddenly moved, Robert shouted to one of the soldiers. Together, they brought the man out and laid him on the ground. His head and face were terribly mutilated, and he had obviously lost a great deal of blood, but he was still alive.

The officer in charge of the party ordered two of the soldiers to escort the wounded American to the local hospital. Robert ran to the ambulance and brought back a stretcher. He assumed the man had to be the pilot since they had found no one else inside. The plane couldn’t have landed itself.

The two Germans carried the American to the ambulance. As Robert was leaving the crash site, the rest of the soldiers were already stripping the aircraft of its machine guns and other valuable equipment.

The boy hoped that the brave American pilot wouldn’t die.

London, England

Claridge’s Hotel

General Henry H. Arnold

1630

Hap Arnold was worn out.

Since arriving in England, he had maintained an arduous schedule of fifteen-hour workdays, during which he met with dozens of the Allied commanders, visited training and maintenance facilities, and inspected many of the bomber and fighter groups.

Earlier that day, Arnold had flown up to Burtonwood, where nearly ten thousand American mechanics and support personnel repaired and maintained the aircraft engines so vital to the fighter and bomber arms.

Afterward, he enjoyed a working lunch at the Savoy Hotel in London, where he was briefed by British commanders on the aerial battle against German U-boats in the North Atlantic as well as the latest intelligence on the Russian front.

He spent the remainder of the afternoon in a leisurely shopping excursion with Ira Eaker, who escorted him to several exclusive shops where he could find special gifts for his family and close friends.

By the time the two generals returned to Claridge’s, it was 1630. General Arnold went up to his suite to rest before dinner. A nervous General Eaker still waited for word from Fred Anderson on the results of the Stuttgart mission. The inordinate delay seemed ominous.

For General Arnold’s last night in England, Eaker had planned a sumptuous supper party at Claridge’s. In attendance would be thirty-six senior Allied army commanders and diplomats in the European theater, including Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal; Marshal of the RAF: the Viscount Hugh Trenchard; Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris; Lord Louis Mountbatten; Air Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory; Roosevelt’s emissary W. Averell Harriman; the American ambassador, John G. Winant; the diplomat Anthony Drexel Biddle, Jr.; and Lieutenant General Jacob Devers, the overall commander of U.S. Army forces in Europe.

General Eaker had made sure his staff pulled out all the stops to make the evening memorable. His dog robbers had done an extraordinary job acquiring the aged beef, fresh seafood, fruit and vegetables that would make it a memorable occasion.

In addition to a substantial array of fine wines, Kentucky bourbon, and other spirits, each guest would celebrate General Arnold’s visit with after-dinner toasts and Eaker’s favorite hand-rolled cigars.