To Hell on a Fast Horse (17 page)

Read To Hell on a Fast Horse Online

Authors: Mark Lee Gardner

ONCE THE GANG WAS

disarmed and fed, they were taken to the Wilcox-Brazil place. Garrett then sent Brazil, Mason, and Rudolph back for Bowdre’s body. Both the posse and the prisoners spent the night at the ranch headquarters, where the possemen took turns watching the prisoners, two guards at a time. Garrett’s orders were that if any of the prisoners tried anything, they were to be shot. After breakfast the next morning, the entire entourage—including Bowdre’s corpse—departed for the Pecos, arriving at Fort Sumner before noon. It was Christmas Eve. As Garrett’s party neared the Indian Hospital, Manuela Bowdre ran out in the snow to confront them.

She frantically looked for her husband with the other prisoners, and then she saw one of Garrett’s men riding her husband’s horse. The men driving the wagon with Bowdre’s body did not want to deal with the visibly angry woman and drove on past her. As Manuela screamed and cussed at Garrett, the two men stopped the wagon, took hold of Bowdre’s body, and carried it into his widow’s quarters and laid it out on a table. When Garrett finally got an opportunity to speak, he told Manuela to go to the store and pick out a suit of clothes for her husband. He would pay for it, and he would pay to have the man buried as well.

The prisoners were taken to the blacksmith shop to be fitted with irons, but, because of a lack of materials or time, only Billy and Rudabaugh were shackled and chained. Wilson and Pickett, obviously deemed the two least dangerous members of the gang, went without irons for the time being. The Kid and Rudabaugh were then led across the plaza to a long, two-story structure that had once served as officers’ quarters but now housed the Maxwell family. Garrett had been approached by Deluvina Maxwell, the Maxwell’s Navajo servant, with a message from Mrs. Luz Beaubien Maxwell. Would Garrett permit the Kid to be brought to their residence so that her daughter, sixteen-year-

old Paulita, could tell the Kid good-bye? The nice-looking sister of Pete Maxwell was not the only Fort Sumner female Billy had wooed in recent months, but she had become his favorite, and the young lady was equally taken with him. Garrett acquiesced, but he told Jim East and Lee Hall, the two guards, to keep a close watch on the Kid.

Before the prisoners and their escort reached the Maxwell place, the shackle on Rudabaugh’s ankle somehow broke loose. “That is a bad sign,” Billy said. “I will die and Dave will go free.” He was not joking—the Kid, it seems, had a superstitious streak. After the prisoners entered the house, Mrs. Maxwell politely asked the guards if they would release Billy so that Paulita and the Kid could say their good-byes privately in another room. East and Hall said no—they had worked too hard to catch the outlaw, and it would take more than these women’s transparent machinations to get him away from them now.

“The lovers embraced,” East wrote later, “and she gave Billy one of those soul kisses the novelists tell us about.”

After a few respectful moments, the guards pulled Paulita and the Kid apart and then escorted the prisoners to Garrett, who was ready to leave for Las Vegas.

With the fighting over and what was left of the gang well in charge, Garrett and Stewart no longer needed the entire posse. It was decided that Barney Mason, Jim East, and Tom Emory would accompany them; the rest of the men were dismissed. The prisoners were loaded into a two-mule wagon loaned by Brazil, who also served as the vehicle’s driver, and with the slapping of the reins and a couple of sucking clicks from Brazil’s clenched jaw, the entire cavalcade departed Fort Sumner, the Kid and Rudabaugh laughing and chatting as if they were on a Sunday stroll. In fact, over the next few days, Garrett learned a lot about Billy Bonney. Tom Pickett, on the other hand, seemed worried, and Billy Wilson was withdrawn and dejected. The wagon made for slow going in the snow, but by about 8:00

P.M

., Gar

rett’s party had reached John Gerhardt’s ranch, twenty-five miles up the Pecos, and stopped for the night. Twelve hours later, the men were back on the road, arriving at Padre Polaco’s Puerto de Luna store at 2:00

P.M

. It was Christmas day, and the jolly Padre Polaco served Garrett, his men, and the prisoners a hearty meal.

The Christmas dinner was served in shifts, and Jim East was the first to guard the prisoners. East and the prisoners were sequestered in a long adobe room in the store building. Its single door was locked, and Garrett had the key in his pocket. East sat on a woodpile near the door, facing the prisoners, who were gathered around the fire-place at the opposite end of the room. After a bit of small talk, the Kid asked East if he had anything to smoke. The guard replied that he did, to which the Kid responded that he had some rolling papers. East got ready to throw the tobacco to the Kid, but the outlaw offered to come over and get it, and with that, he and Rudabaugh started for the guard’s end of the room. They were halfway across the open space when East shouted to them:

“Hold on, Billy, if you come any farther I am going to shoot you.”

The prisoners kept coming; East leveled his gun at them.

“Hold on, Billy, if you make another step I’ll shoot you.”

The prisoners hesitated.

“You are the most suspicious damned man I ever saw,” Billy said, feigning disgust, and then he and Rudabaugh turned around and walked to the fireplace.

East pitched the tobacco over to the Kid, but he picked it up and tossed it right back; Billy did not want East’s damn tobacco.

Garrett was able to get Wilson and Pickett fitted with irons at Puerto de Luna, and later that afternoon, the party started again for Las Vegas. They traveled all through the night and rode into the San Miguel County seat about 4:00

P.M

. on December 26. Not in their wildest dreams could these trail-worn westerners have imagined the excitement and extreme curiosity their arrival generated. It was as if

the circus had come to town with horses prancing, elephants trumpeting, and clowns frolicking. Indeed, with Garrett as the taciturn lion tamer and Billy the Kid as the caged-beast-that-cannot-be-tamed, it had all the makings of the greatest show on earth—or a tragedy for the ages.

Facing Death Boldly

Billy never talked much of the past; he was always looking into the future.

—

FRANK COE

I

T HAD NOT BEEN

easy, but Pat Garrett kept his promise to the outlaws. Despite a well-armed lynch mob at the train station in Las Vegas, he had gotten Billy, Wilson, and Rudabaugh safely to Santa Fe. Once he turned the prisoners over to Deputy U.S. Marshal Charles Conklin, however, he believed his job was done. Garrett did not travel to Mesilla to witness the Kid’s trial for Sheriff Brady’s murder. He had plenty to keep himself busy as the new sheriff of Lincoln County, which he officially became on January 1, 1881. During the humdrum workdays of serving writs, collecting taxes, and completing annoying paperwork, he may have wondered if he would ever see the Kid again. When the Kid’s trial ended in a guilty verdict, there was no more wondering. Judge Bristol ordered that Billy be transported to Lincoln, where he was to be placed in Sheriff Garrett’s care until May 13, on which date the sheriff was to conduct a public hanging. Garrett had

never hanged a man, but a bigger concern was how to hold the Kid until the execution date.

Garrett took custody of Billy on April 21. The sheriff confined the county’s prisoners in makeshift quarters on the second floor of the two-story adobe courthouse (formerly the Murphy-Dolan store) on the west end of Lincoln. Billy would be incarcerated on that floor as well, but in a room all to himself. Well aware of the building’s shortcomings as a jail, Garrett assigned two guards to watch the Kid: Bob Olinger and friend James W. Bell.

Olinger was born Ameredith Robert B. Olinger in Delphi, Indiana, in 1850. Ten years later, the Olinger family was scratching out a living on a farm in Linn County, Kansas. After a sojourn in Indian Territory (Oklahoma), Bob followed his older brother John Wallace to the Seven Rivers country of southeastern New Mexico in 1877, where they seem to have divided their time equally between chasing cattle and men, particularly the Regulators. In October 1880, Olinger was commissioned a deputy U.S. marshal for Lincoln County and spent several weeks with Deputy Marshal Pat Garrett hunting counterfeiters and rustlers, especially the Kid’s bunch. On April 10, 1881, Sheriff Southwick appointed Olinger a deputy sheriff for Doña Ana County with the special task of delivering the Kid to Garrett in Lincoln.

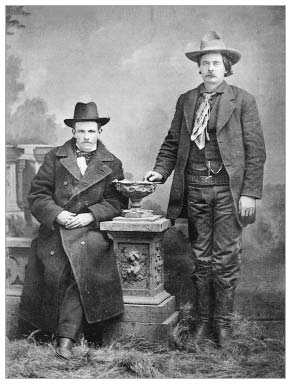

Only three photographs survive of Bob Olinger. Now spotted and yellowed with age, the photos reveal a sizable man, someone the

Las Vegas Daily Optic

described as “the tall sycamore of Seven Rivers.” Perched upon his head, making him appear even taller than his six feet two inches, was a wide-brimmed hat, and like most men of the time, Olinger wore a vest and coat. Around his collar he liked to sport a colorful bandanna, neatly tied, its long ends dangling down the front of his chest. From his vest swung a watch chain and fob. He had a rather expressionless face (not uncommon in nineteenth-century portraits), and his modest mustache failed to make him look distinguished

in any way. Some photographs are able to hint at a subject’s character or personality—these do not. But in the case of Bob Olinger, there is no lack of opinion regarding the man’s character.

Jimmy Dolan and Bob Olinger.

Robert G. McCubbin Collection

Olinger had acquired a reputation as a bully, at least among his enemies, of which there were many. Texas Ranger James Gillett, on a visit to Roswell, was told in no uncertain terms that Bob Olinger was the meanest man in New Mexico. Gus Gildea wrote that Olinger “hated anyone who he could not bluff. I knew him well and considered him a coward.” The most damning assessment, however, came from Pat Garrett, who said that Olinger “was born a murderer at heart. I never slept out with him that I did not watch him.”

“Of course,” Garrett added, “you will understand that we had to use for deputies such material as we could get.”

It was Olinger’s killing of John Jones on August 29, 1879—a chilling murder according to most accounts—that created bad blood between him and the Kid. Billy had a warm relationship with the Jones family, and even though he and the Joneses had been on opposite sides during the Lincoln County War, they remained good friends. “Don’t let any of your boys bother Bob Olinger,” Billy told a grieving Heiskell and Ma’am Jones in the front yard of their Seven Rivers home. “I will get him.” Olinger knew about Billy’s grudge, but he put little stock in the Kid’s reputation, dismissing the outlaw as nothing but a cur. “There existed a reciprocal hatred between these two,” Pat Garrett wrote later, “and neither attempted to disguise or conceal his antipathy from the other.”

Unlike Olinger, James W. Bell was well liked by most everyone. Bell had served in the White Oaks posses, and he had helped Garrett transport the Kid, Wilson, and Rudabaugh from Las Vegas to Santa Fe back in December. Only twenty-seven years old and a native of Georgia, he had tried his luck at gold mining in White Oaks until his appointment as a deputy U.S. marshal, an often dangerous job but one with a more reliable income. “Mr. Bell is a very cool and daring man,” observed a newspaper correspondent. “The citizens of White Oaks have full confidence in him and believe that he will conscientiously discharge his duties at any cost.”

As Billy’s guards, both Bell and Olinger served in the capacity of deputy sheriffs under Garrett, although their duties also included tending to the other prisoners in the courthouse, then numbering five men. Billy’s room, located in the northeast corner of the courthouse, featured two double-hung windows, one facing north and the other east, giving the Kid a nice view of Lincoln’s dusty main street and its lackluster comings and goings. Across the street to the northeast, and set back from the road, was the single-story adobe hotel owned

by Sam Wortley. All the county prisoners were taken to the hotel for their meals; Billy’s meals were prepared at the hotel restaurant and brought to him.

The Kid wore leg shackles and handcuffs at all times—well, sort of. Both cuffs were actually locked on one wrist. This was convenient at mealtime and for visiting the outhouse, but it also allowed the Kid dangerous flexibility, a situation that would not have been tolerated at the Mesilla jail. Located between Billy’s room and the second floor’s main north-south hallway, was Garrett’s office, which made it easy for the sheriff to visit with his prisoner. Billy gave Garrett all kinds of excuses for each crime or killing he had been connected with, except for the killing of White Oaks blacksmith Jimmy Carlyle.

“That was the most detestable crime ever charged against you,” Garrett said one day to Billy.

“There’s more about that than people know of,” the Kid answered defensively but did not bother to elaborate.

Garrett could see that Billy liked Deputy Bell, who showed no ill will toward the Kid, even though Bell had been a friend of Carlyle. Olinger, on the other hand, like any other bully, enjoyed taunting the Kid at any opportunity and making his prisoner aware of the power he held.

“He used to work me up until I could hardly contain myself,” Billy told a friend.

Like many before them, Olinger and Bell underestimated their young prisoner. In a pinch, William H. Bonney could be as ruthless and cold-blooded as any outlaw and thug who plagued New Mexico Territory. When life and death hung in the balance—Billy’s, that is—that was the time to be most cautious around the Kid. Everyone knew he was a killer. Everyone had heard about his flair for escaping tight spots. If you could read, all you had to do was to pick up one of the Territory’s newspapers to see that Billy had been talking of escape ever since his confinement at Santa Fe. But Billy’s real and deadly talent was fooling people. Time

and again, they misjudged the diminutive outlaw’s abilities and resolve. Billy joked and smiled, but his quick mind was always sizing up the situation, looking for a sign of weakness, a slight mental error, something that would give him an edge.

Foolishly, Olinger and Bell brushed aside several pointed warnings, from Sheriff Garrett and others, to be extremely careful around the Kid. Even back in Mesilla, a man had noticed Olinger’s indifference and tried to talk some sense into him:

You have guarded many prisoners, and faced danger many a time in apprehending them, and you think that you are invincible and can get away with anything. But I tell you, as good a man as you are, that if that man is shown the slightest chance on earth, if he is allowed the use of one hand, or if he is not watched every moment from now until the moment he is executed, he will effect some plan by which he will murder the whole of you before you have time to even suspect that he has any such intention.

Bob Olinger, his arrogance in peak form, smiled at the man, saying there was as much chance of the Kid escaping as there was of the Kid going to heaven.

More than once, Garrett’s deputies demonstrated an unfathomable lack of good judgment around the Kid. On April 26, Olinger stupidly left his pistol loose on a table in front of Billy. Someone quickly snatched up the gun, no doubt imagining that they had prevented a bloody melee. But something must not have been quite right about the situation, or the Kid would have made a grab for Olinger’s pistol. No, Billy was biding his time, all the while allowing, if not encouraging, the guards their lackadaisical attitude toward him. Olinger boasted to one Lincoln man that it did not matter whether the Kid wore his irons or not—there was no way he could get away. Olinger even laughingly told Garrett he could turn Billy loose and herd him like a goat.

ONE OF GARRETT’S IMPORTANT

duties as county sheriff was to collect taxes and business license fees, an arduous and time-consuming job in a county as large as Lincoln. So on April 28, a Thursday, Garrett was collecting the taxes in White Oaks. Back in Lincoln, Bell and Olinger went about their daily routines, which, for Olinger, meant goading the Kid. That morning he made sure Billy was watching as he loaded his shotgun, a Whitney double-barrel 10 gauge. It was a fairly unusual weapon in that it had two trigger guards and three triggers under the receiver. The forward trigger was a release that opened the breechloader for access to the gun’s two chambers. Olinger carefully slid in two shotshells, each loaded with 18 buckshot, then snapped the barrels back in place. As he did this, he looked at the Kid and said, “The man that gets one of those loads will feel it.”

“I expect he will,” Billy calmly said, “but be careful, Bob, or you might shoot yourself accidentally.”

At approximately 6:00

P.M

., suppertime, Olinger took all the prisoners except the Kid across the street to Wortley’s for their evening meal. As soon as Billy could no longer hear the voices of Olinger and his prisoners, he asked Bell to take him to the privy, which was out behind the courthouse. It was a necessary chore that Bell and Olinger undoubtedly performed several times a day, not just with Billy but with the other prisoners as well. But with Garrett out of the equation and Olinger out of sight, the Kid figured his odds were as good as they were going to get.

After finishing at the privy, the Kid and Bell reentered the building and started up the staircase to the second floor, Billy moving slowly because of the shackles on his ankles, Bell coming up behind. At the top of the staircase, the Kid suddenly whirled around and struck Bell a violent blow to his head, perhaps two, with the arm that held his handcuffs. Wincing from the pain, and with blood spurting from an

ugly wound (one report stated that the blow was so severe it broke Bell’s skull), the deputy still managed to put up a good fight. He and Billy tumbled to the floor, the Kid struggling with Bell for his pistol. In the scuffle Billy somehow managed to wrestle away the six-shooter, and the deputy decided to flee his attacker. He broke loose from the Kid and scrambled down the staircase. Billy, flat on his stomach in a pool of Bell’s blood, raised the pistol. He may have called out for Bell to stop, and then he pulled the trigger. Some townspeople claimed they heard three shots come from the courthouse, but only one bullet struck Bell. And that one was a fluke, ricocheting off the adobe wall of the staircase before entering Bell’s right side and ripping completely through his body. It was not Billy’s best shooting, but it did the trick. Bell, on his feet through pure adrenaline, made it to the bottom of the stairs and stumbled out the southwest door, where he collapsed into the arms of Gottfried Gauss, a part-time county employee. Bell died without saying a word.

The Kid jumped up and went just a few feet down the upstairs hall to his right and broke into the armory. He quickly made an assessment of the weapons and ammunition, grabbed Olinger’s shotgun and other firearms, and then hurriedly shuffled down the hall to the front of the building. He turned into Garrett’s office and passed through to his own quarters, where he looked out the north and east windows for any activity on the street below, particularly any evidence that Bob Olinger had heard the shots too. Billy rightly guessed that he had.

At Wortley’s, Olinger bolted up from his table and said, more to himself than anyone else, “They are having a fight over there.”

He rushed out of the hotel and across the street to the courthouse. Because the only access to the second floor was from a room in the rear of the building, Olinger headed directly for the courthouse’s northeast corner, where a gate opened to a path along the east side of the structure to the horse corral behind. Billy had no trouble seeing big Bob Olinger coming. As Olinger stepped through the gate, the

Kid, poised at the open east window, pulled back the hammers to both barrels of the Whitney until they clicked at full cock. At the same time, Gauss appeared at the corral gate.