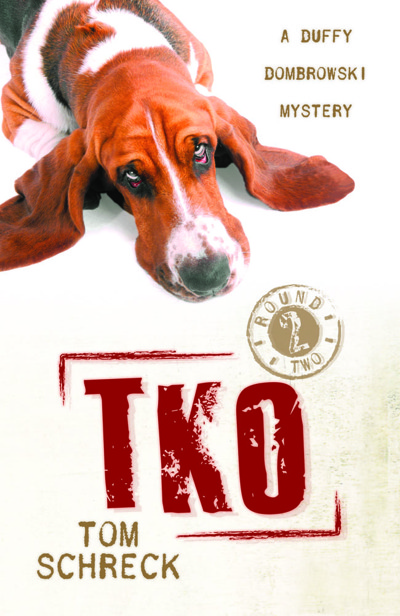

TKO

Copyright Information

TKO

© 2011 Tom Schreck

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any matter whatsoever, including Internet usage, without written permission from Midnight Ink, except in the form of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

As the purchaser of this ebook, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. The text may not be otherwise reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or recorded on any other storage device in any form or by any means.

Any unauthorized usage of the text without express written permission of the publisher is a violation of the author’s copyright and is illegal and punishable by law.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

First e-book edition © 2011

E-book ISBN: 978-0-7387-2044-9

Book design by Donna Burch

Cover design By Gavin Dayton Duffy

Cover dog image © Henryk T. Kaiser/The Stock Collection/Punchstock

Midnight Ink is an imprint of Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

Midnight Ink does not participate in, endorse, or have any authority or responsibility concerning private business arrangements between our authors and the public.

Any Internet references contained in this work are current at publication time, but the publisher cannot guarantee that a specific reference will continue or be maintained. Please refer to the publisher’s website for links to current author websites.

Midnight Ink

Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

2143 Wooddale Drive

Woodbury, MN 55125

www.midnightink.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dedication

For the two Mrs. Schrecks,

Sue and Annette … the loves of my life.

You can’t beat me. I’m God!

Muhammad Ali

Well, God’s getting knocked on his ass tonight, then.

Joe Frazier

1

“Just because a guy

slits the throats of two high-school cheerleaders, axes the back of the quarterback’s head, and runs down the class president in his mom’s LTD, doesn’t make him a bad guy,” I said.

“Duff—”

I didn’t let Monique finish.

“Howard’s father split before he was born, his mom was abusively schizo—shit, she used to strip him naked and make fun of his Johnson when he was in high school—and every day the football players would give him a wedgie.”

“So every kid who gets a hard time in high school should be excused for homicide?” Monique said.

“No—that’s not what I’m saying.” I realized I had been raising my voice. “All I’m saying is given what was going on in his head, it’s no wonder he flipped out. In a way, they all had it coming.”

Monique gave me a look and then went back to her desk.

A long time ago, back in high school, Howard Rheinhart went away to Green Haven for murdering four of his classmates. He was bullied and abused right from first grade, and one day while he was receiving his daily wedgie from the McDonough High’s all-city quarterback, Mark Woroby, two of the cheerleaders went into an impromptu cheer. That night, after the hoop game with Eagle Heights, Howard held his own homecoming. It meant releasing years of pent-up anger, and boy, did Howard ever make up for lost time.

Carl the janitor found the two cheerleaders, Danielle Thomson and Terri Snow, in their uniforms, sitting in the bleachers, still in their uniforms. “Go Team” was scripted in dried blood on the gym floor in front of the somewhat pale pep squad. Carl’s been on medication ever since.

The cheerleaders had taken the time to make Howard’s daily humiliation that much more dehumanizing. They literally cheered his abuse and they made it clear he didn’t matter. When Howard slit their throats, he proved that he did, in fact, matter quite a bit.

Woroby, the QB, was found decapitated Monday afternoon in a field outside of town. His body was propped up against a tree, his right arm cocked back like he was throwing long, except his head was where the ball would usually be. There was no questioning the fact that Howard had a flair for sarcasm, but you didn’t have to be a Freudian analyst to see what kind of statement he was making. For the first time in his life, well, technically the second, Howard was turning the tables and letting everyone know that the joke wasn’t on him. Unfortunately, a lot of people didn’t appreciate his sense of humor.

Class president and all-around high-school stud Jack Powers wasn’t guilty of wedgersizing Howard on a daily basis. He did mockingly nominate him for “most likely to succeed” and was leading a campaign to have Howard win as a joke until the student advisor, Mrs. Kyle, put a stop to it. Howard flattened Powers, gunning the eight-cylinder LTD from two blocks away and never slowing down.

It was Howard’s way of saying that he would not be mocked, that he was an individual too, and that he demanded to be treated like one. He went from total victim position to total dominance in a matter of days. Sure, he went overboard; sure, he might have been better off with a little assertiveness training; and sure, one might say that his actions were a bit out of proportion. But did anyone stop to think what that guy must of felt like day after day, getting abused at home and at school and just about everywhere he turned?

They arrested Howard in Canastota at a Thruway rest stop, listening to Frampton sing “Do You Feel Like We Do.” It’s a pretty fair bet that no one did quite feel like Howard Rheinhart back in high school. It was probably a pretty good bet that now that he had been released from prison, no one quite felt like him today either. He did his pretty lenient thirty-year sentence and was let out on time served. Here he was, back in Crawford, living in a parole halfway house and assigned to my caseload at Jewish Unified Services. The geniuses at the parole board discharged Howard with the provision that he get intense psychiatric care. He had his youthful offender status at the time of the murders to thank for his relatively quick release.

The problem was, Howard had no income, no savings, and no friends. That meant he was on Medicaid and that his intensive psychiatric care would involve seeing me three times a week and Dr. Jeriah Abadon, our consulting psychiatrist, once a week. I am a human services counselor with very little education and a few years experience. I’m used to handling alcoholics and addicts, teenagers who get in trouble, and guys whose jobs mandate that they get counseling or else face unemployment. I’m not renowned for my skills with deeply psychiatric multiple killers.

Howard had only been coming to see me for about a week and a half. He was never late, said very little, and acted as skittish as anyone I ever saw. I guess thirty years in prison preceded by seventeen years of wedgie-filled torment will do that to a guy. All I wanted to see the man do was learn to trust people a little bit and not go through life fearing that around the corner someone was always waiting to hoist him up by the elastic in his skivvies. Last Friday, on his fourth visit, Howard said something to me that I’ll never forget. I had asked him what he wanted out of life, and he hesitated for a long time.