Titanic (9 page)

Authors: Deborah Hopkinson

Captain Smith was relying on his long experience. After all, he had crossed the Atlantic many times safely. He’d once told the

New York Times

: “. . . when anyone asks me how I can best describe my experience in nearly 40 years at sea, I merely say uneventful. Of course there have been winter gales, and storms and fog and the like, but in all my experience, I have never been in any accident of any sort worth speaking about.”

Earlier, around 5:50 p.m., Captain Smith had called for an alteration in course to South 86° West, slightly to the south and west of the normal route. The ship’s course called for a change in direction at a certain spot in the ocean, which was called “turning the Corner,” to follow a more direct westward course heading toward Nantucket, off the coast of Massachusetts.

But this precaution would not necessarily be very effective, as the

Titanic

was still far enough north that she would remain in the area of ice. In other words, Captain Smith seemed confident — in hindsight, overly confident — that if any iceberg large enough to cause any damage appeared, the lookouts and the officers on the bridge would be able to see it in time.

And so Captain Smith left the bridge about 9:25 p.m., saying to Lightoller, “‘If it becomes at all doubtful let me know at once; I will be just inside.’”

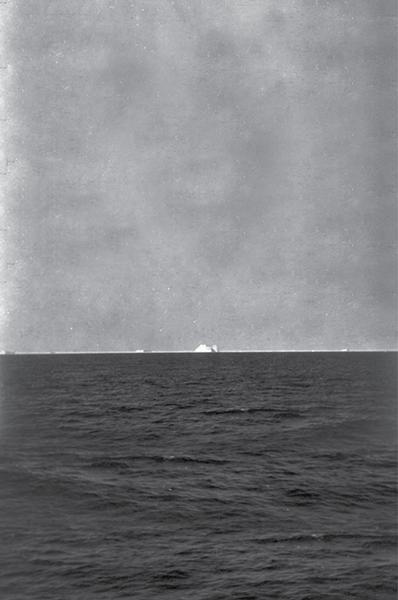

(Preceding image)

A distant photograph of the iceberg that is claimed to have sunk the

Titanic

.

In latitude 42 N. to 41.25, longitude 49 W. to longitude 50.30 W., saw much heavy pack ice and great number large icebergs, also field ice, weather good, clear.

— Mesaba

to

Titanic

, April 14, 1912, 9:40 p.m.

The night kept getting colder.

On the bridge, Second Officer Lightoller knew the ship would be entering an area of ice soon. Just after the captain left, he asked James Moody, the junior officer on duty, to call the crow’s nest. Lightoller gave instructions for Moody to pass on: He wanted the men to keep a sharp lookout throughout the night for ice, particularly small ice and growlers.

At 9:40 p.m., twenty minutes before the watch changed at 10 p.m., a message came into the radio room from a ship called the

Mesaba

warning of heavy pack ice and large icebergs. Where? Right ahead of the

Titanic

.

Yet this message didn’t contain the prefix MSG, marking it a priority message from captain to captain. Harold Bride was off duty, taking a nap. Both operators were still trying to catch up on their sleep — they’d been up most of Friday night repairing their equipment. Jack Phillips was swamped with passenger messages.

For all these reasons, somehow the warning from the

Mesaba

just didn’t make it to the bridge.

Lightoller said later, “The wireless operator was not to know how close we were to this position, and therefore the extreme urgency of the message.”

Would getting that message have made a difference in what happened that night? Maybe. But maybe not.

After all, the ship had already received several warnings. And still the captain hadn’t put additional lookouts into place. Nor had he given an order for the ship to go slower — even though a ship as large as the

Titanic

was not easy to turn.

Walter Lord, author of

A Night to Remember

, the most famous book about the

Titanic,

put it this way: “Above all, the cumulative effect of the messages — warning after warning, the whole day long — was lost completely. The result was a complacency, an almost arrogant casualness, that permeated the bridge.”

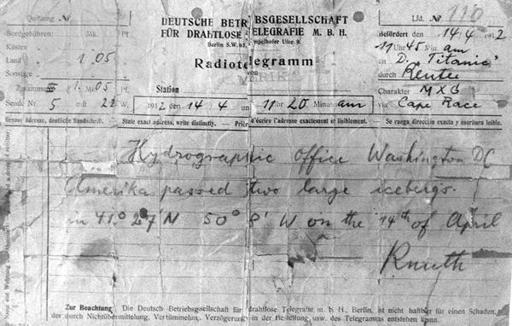

(Preceding image)

A radio telegram from the German ship

Amerika

to the

Titanic

, warning the crew of icebergs.

Ten o’clock came.

Lightoller handed the watch over to First Officer William M. Murdoch. The ship continued to steam full speed ahead — about 22½ knots (a knot is equivalent to 6,076 feet or 1.151 miles an hour).

In the crow’s nest, lookouts Reginald Lee and Frederick Fleet arrived to relieve George Symons and Archie Jewell. Symons and Jewell passed on the orders from Lightoller: Keep a sharp lookout for small ice and growlers.

“All right,” replied Frederick Fleet. At twenty-four, he had already had four years’ experience as a lookout on the

Oceanic

before joining the

Titanic

.

As seven bells (11:30 p.m.) rang, it was still cold, clear, and calm. Most of the men, women, and children on the

Titanic

had turned in for the night, lulled by the now-familiar hum of the engines. About this time Frederick Fleet said he noticed “a sort of slight haze.” Along with the calm, flat sea, a haze could make spotting ice even more difficult.

Then, just before 11:40 p.m., Fleet spied what looked to him like a dark mass straight ahead. It appeared to be directly in the

Titanic

’s path. Fleet sounded the warning bell with three sharp rings and telephoned down to the bridge: “‘Iceberg right ahead.’”

Sixth Officer Moody picked up the phone. “‘Thank you,’” he answered, and hung up.

“I reported it as soon as ever I seen it,” Fleet testified later. “I reported an iceberg right ahead.”

It had seemed small when he first spotted it — maybe the size of two tables put together. But it soon loomed larger, a dark shape rising high above the calm surface of the sea.

On the bridge, First Officer William Murdoch, an experienced seaman, had probably already spotted the shape on his own. He went into action.

Each second was critical, and there wouldn’t be many of them. The exact sequence of what happened next — or should have happened — is still unclear.

One thing is certain, though. Murdoch had little time and few good options.

Murdoch didn’t want to hit the iceberg full on. The ship’s bow would probably have been crushed in a head-on collision. And it’s likely the accident would have resulted in severe injuries and even death to some passengers and crew. It’s possible that with the damage from a head-on collision the

Titanic

might have remained afloat long enough for rescue ships to arrive. But Murdoch couldn’t know what would happen. And no seaman deliberately crashes a ship.

So Murdoch did what he could to try to avoid an accident. He would try to steer around the iceberg, hoping that the damage, if there was any, would be less serious than a head-on collision. It wouldn’t be easy. After all, the

Titanic

was a 46,000-ton object moving at 38 feet a second.

The

Titanic

was probably only about three ship lengths from the iceberg when Murdoch gave his first order. He aimed to turn the ship to the left as quickly as possible to avoid a direct hit. Fourth Officer Boxhall testified, “I heard the first Officer give the order, ‘Hard-a-starboard,’ and I heard the engine room telegraph bells ringing.”

Sixth Officer Moody, standing behind quartermaster Robert Hichens at the ship’s wheel, repeated the instruction. Hichens carried it out, turning the wheel hard over. Murdoch also ordered astern full, probably on the starboard engine.

Fred Barrett, a stoker in Boiler Room 6, the most forward of the ship’s boiler rooms, was surprised to suddenly see a red light flash. He knew this was the signal to start closing the dampers to shut off the engines. But what he couldn’t figure out was why he was being ordered to stop the engines now — on such a calm, clear night.

Meanwhile, up on the bridge, the flurry of activity continued, with everything seeming to happen at once.

Murdoch quickly activated the switch to close the ship’s automatic watertight doors in the compartments below to help contain any flooding. The stern of the great ship swung close to the iceberg. At some point Murdoch probably also ordered “hard-a-port” to try to maneuver around the berg. As researcher David G. Brown has noted, “Murdoch’s hard-a-port order would have swung the stern away from the bow.” In this way, Murdoch was able to limit the damage to the bow.