Titanic (19 page)

Authors: Deborah Hopkinson

At about 2:15 a.m., just a short distance away from Colonel Archibald Gracie, Jack Thayer could see the water rising up over the deck, the ship going down at a fast rate, the sea coming right up to the bridge. The crowd kept pushing back toward the stern, which was still dry. Shock and terror showed on people’s faces.

Without warning, the ship seemed to start forward and sink at a lower angle. Jack heard a rumbling roar and what seemed to be muffled explosions.

As the bow sank lower, the weight of the water was straining the ship’s steel structure to the breaking point. Jack couldn’t believe the sound: “It was like standing under a steel railway bridge while an express train passes overhead, mingled with the noise of a pressed steel factory and the wholesale breakage of china.”

Jack and Milton decided to jump into the water at the last second and then swim as fast as they could away from the ship to avoid being dragged down by suction or hit with debris.

“We had no time to think now, only to act,” said Jack. “We shook hands, wished each other luck. I said, ‘Go ahead, I’ll be right with you.’”

Milton went first, disappearing over the rail. Jack never saw him again.

Then it was his turn.

Ole Abelseth also saw that time was running out. “. . . we could see the water coming up, the bow of the ship was going down, and there was a kind of an explosion.

“We could hear the popping and cracking, and the deck raised up and got so steep that the people could not stand on their feet on the deck. So they fell down and slid on the deck into the water right on the ship. Then we hung onto a rope in one of the davits. We were pretty far back at the top deck.”

Like Jack, Ole and his companions wanted to wait until the very end to leave the ship. By the time Ole was ready “. . . it was only about five feet down to the water when we jumped off. It was not much of a jump. Before that we could see the people were jumping over. There was water coming onto the deck, and they were jumping over, then out in the water.

“My brother-in-law took my hand just as we jumped off; and my cousin jumped at the same time. When we came into the water, I think it was from the suction — or anyway we went under, and I swallowed some water. I got a rope tangled around me, and I let loose of my brother-in-law’s hand to get away from the rope.”

One thought came into his mind: “I am a goner.”

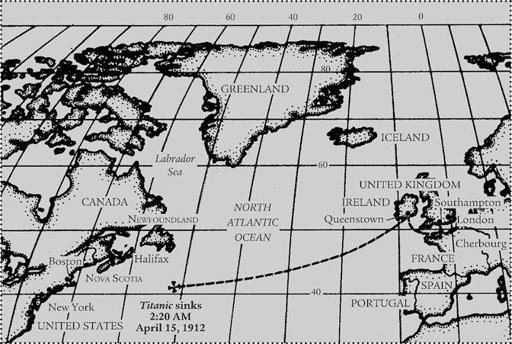

(Preceding image)

A map showing the

Titanic

’s ill-fated course.

The ship was now in its final moments. As the bridge went under, the ship’s funnels tilted forward. The weight of the enormous structures caused the cables holding the front funnel to snap. As it fell, the air filled with soot, and streams of sparks shot into the black, star-studded sky.

The gigantic funnel hit the sea with a horrific crash, crushing anyone in the water below it. It barely missed Collapsible B, which had shot forward from the port side into the water and was now on the ship’s starboard side. The splash from the funnel hitting the sea tossed the lifeboat, throwing off some of those desperately clinging to it. At the same time, Collapsible A, which had originally been on the starboard side, floated to port.

These two boats, one now bobbing upside down in the frigid sea, were the last hope for anyone left on board or struggling in the water for life.

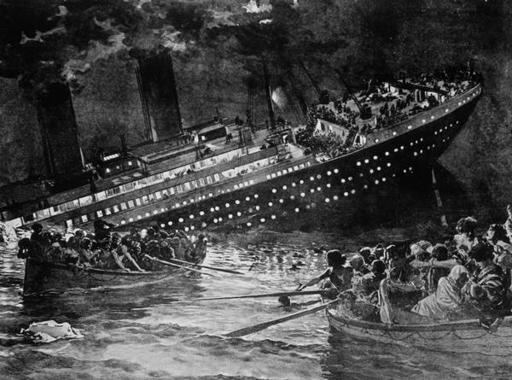

(Preceding image)

An illustration that appeared in a London magazine,

The Sphere

, on April 15, 1912, shows the

Titanic

sinking as passengers in lifeboats watch in horror.

“The water was intensely cold . . .”

— Charles Lightoller

Some survivors watched the

Titanic

sink from lifeboats a mile away. Others, like young Jack Thayer, had a close-up view.

Really

close.

Jack was standing near the second funnel in the ship’s final moments when his friend Milton Long slid down the side of the ship into the water. Seconds later, Jack threw off his overcoat and climbed onto the rail. But, unlike Milton, he jumped away from the ship, a decision that probably saved his life.

“The cold was terrific,” he said. “The shock of the water took the breath out of my lungs. Down and down I went, spinning in all directions.”

Shock? No wonder. The water was twenty-eight degrees Fahrenheit, below freezing. Painfully, deadly cold. Water that cold makes it hard to think or even to breathe. Fingers get stiff. It’s almost impossible to grasp anything, to hold on. Most people begin to freeze in a matter of minutes.

Jack wanted to get as far from the

Titanic

as he could. He feared getting sucked down with the ship or crushed by falling debris. When he surfaced, lungs bursting, he was forty yards away from the foundering giant.

Then a strange thing happened. Jack knew — absolutely knew — that he should keep moving. He should find something to grab, look around for a lifeboat. His life depended on it.

Instead, he couldn’t take his eyes off the unbelievable sight before him.

Jack saw hundreds of people on board rushing back toward the stern, which was now rising higher and higher into the air. The stern continued to tilt up until it was perhaps 250 feet out of the water. People trying to climb up toward the stern had a hard time. Many simply toppled into the sea as the angle became too great.

The noise was horrific. Everything inside the boat was crashing around — machinery, ovens, beds, mirrors, china, pianos, chairs, and tables. As the bow dropped below the surface, anything that floated rolled wildly in the water.

Anyone still inside the ship, especially anyone belowdecks, had virtually no chance of getting out.

All at once, Jack realized he was in danger from more than the freezing water. As the ship foundered, the gigantic second funnel appeared to lift off in a cloud of sparks.

“It looked as if it would fall on top of me,” he said. “It missed me by only twenty or thirty feet. The suction of it drew me down and down, struggling and swimming, practically spent.”

The ship was breaking apart. As the bow sank, the weight of the aft section, which contained the engine rooms, was simply too great a pressure for the hull to withstand — the hull began to fracture.

Incredibly, the ship’s lights still blazed, thanks to the work of the engineers below who never had a chance at a lifeboat.

At 2:18 a.m. the lights went out, plunging the scene into an eerie darkness.

Minutes earlier, as seawater gushed over the deck, Second Officer Charles Lightoller had simply walked into the water. Like Jack, he was shocked by the intensity of the pain from the cold.

“Striking the water was like a thousand knives being driven into one’s body, and, for a few moments, I completely lost grip of myself — and no wonder for I was perspiring freely, whilst the temperature of the water was 28 degrees, or four degrees below freezing.”

Soon Lightoller found himself pinned against the wire grating of one of the

Titanic

’s huge air shafts — a shaft he knew went all the way down to the very bowels of the ship. He struggled and kicked for all he was worth, but it was impossible to free himself. “. . . as fast as I pushed myself off I was irresistibly dragged back, every instant expecting the wire to go and to find myself shot down into the bowels of the ship.”

Lightoller realized he was drowning: “. . . another couple of minutes would have seen me through. I was still struggling and fighting when suddenly a terrible blast of hot air came up the shaft, and blew me right away from the air shaft and up to the surface.”

Lightoller was in a precarious situation — caught in the chaos as the massive ship began to break apart. He got free of being pinned against the air shaft, but in the next instant he was sucked down against a grating.

And then, suddenly, he could breathe; he had come up to the surface again. By some miracle he found himself by Collapsible B — the very same Engelhardt emergency lifeboat he and Sam Hemming had wrangled off the roof.

Lightoller wasn’t alone in the water. He could hear people screaming around him. He had no strength to get into the boat. And even if he wanted to, he actually couldn’t get in. No one could. The lifeboat had floated off the

Titanic

’s deck upside down — and it stayed that way.