Time Will Run Back (29 page)

Read Time Will Run Back Online

Authors: Henry Hazlitt

“Now

that

sounds interesting, chief. Just how would you do that?”

“Well, let’s think it out. We allowed people first to exchange their ration coupons and then to exchange their consumption goods. And as a result a market was established. Certain exchange ratios, certain relative market values, established themselves. And now we know, for example, that people considered collectively value a chair by four times as much as a shirt, and so on. So we now know how much consumption goods are worth. But we still don’t know how much it costs us to make them. But suppose we knew how much

production

goods were worth? Suppose we knew the

exchange

value, the

mar\et

value, of each piece of land, of each tool or machine, of each hour of every man’s labor-time?

Then

we would be able to calculate costs!

Then

we would be able to know, for each particular commodity, whether or not the value of the finished product exceeded the value of the costs that went into it—whether or not the value of a given

output

exceeded the value of a given

input.”

“You’ve got hold of something there!” said Adams, almost eagerly. Then his countenance slowly fell. “But I don’t see how we can work it out!”

“Establish a market in production goods!” exclaimed Peter.

“How?”

“At present, Adams, the Central Planning Board decides how much shall be produced of hundreds of different commodities. It allots production quotas to each industry. The heads of these industries in turn allot production quotas to the individual factories. Then, on this basis, so much raw material is allotted to each industry and each factory and so many workers are allotted to each industry and each factory. And so on. Now, let’s change this. Let each industry

bid

for raw materials and

bid

for labor, as people do in the consumption goods market, and let these raw materials and this labor go to the highest bidder!”

“At what prices, chief? At what wage rates?”

“Why, at the highest prices and the highest wage rates that are bid!” “In what would these prices and wages be payable?” “Why... in cigarette packages, I presume.” Adams looked dubious. “Have we got that many cigarette packages?”

“We wouldn’t have to exchange

actual

cigarette packages,” suggested Peter. “We could just cancel debts and credits against each other. In other words, cigarette packages would not be so much a—medium of exchange as just a—a standard of value. They would enable us to keep accounts, by supplying a common unit of measurement.”

Adams still looked dubious. “You say that raw materials and labor would go to the industry managers who bid the highest prices or wage rates. What would prevent prices and wage rates from soaring to the skies?”

“Why, Adams, if a manager bid too high for raw materials or for labor, then his production costs would exceed the value of his product; his input would exceed his output.”

“So?”

“So—he would be removed for incompetence.”

“And suppose the manager bid too low?”

“Then he would not get either labor or raw materials.”

“And the product assigned to him would never be produced?”

Peter was stumped. “I suppose,” he conceded, “we would have to remove him also for incompetence.”

“It might be even more effective, chief, to have him shot.”

“At that rate our managers would have to be awfully good guessers, Adams!”

“The survival of the fittest, chief.”

“Or the luckiest!”

They were both silent again.

“No,” admitted Peter after the pause, “I’m afraid my analogy was a false one. We can have markets in consumption goods because these goods

belong

to the people who are exchanging them. Therefore a man will only exchange a given quantity of, say, beets, that he does not value so much, for a given quantity of, say, apricots, if he himself really values that acquired quantity of apricots more than that surrendered quantity of beets—and also if he doesn’t think he can get any more than that for his beets. Now it isn’t hard for a man to tell whether he himself likes apricots better than beets, or any commodity A better than commodity B. But for a man, a manager, to bid for something he won’t really own by offering something else that he doesn’t really own...”

“I think, chief,” put in Adams, “that you’re too ready to abandon your own idea. I’m beginning to think it’s very promising. Now when your managers bid against each other—”

“By the way, Adams, it just occurred to me: What would these managers have to bid with? What would they have to offer in exchange for the raw materials and labor they wanted?”

He seemed unaware that he was now taunting Adams with the same question that Adams had stopped him with a little while back.

“Well, they will just... name figures,” suggested Adams vaguely. “Or,” he added suddenly, “maybe the Central Planning Board could

allocate

a certain hypothetical number of packages of cigarettes to each industry and each factory manager to use for bidding purposes.”

“Then each manager’s bids, Adams, would be limited by the amount of cigarettes the CPB allotted to him?”

Adams nodded.

“Then why not save needless complication,” suggested Peter, “by having the board continue to allot the raw materials and labor

directly,

as it does now? After all, it would only be doing the same thing

indirectly

by allotting the cigarettes to the managers to pay for the raw materials and labor.”

“There’s a difference, chief. The cigarette allotment system would leave more room for managerial discretion. True, the managers would still be limited in the total resources they could apply to the output of the particular product assigned to them. But at least

they,

instead of the CPB, would decide the

proportions

in which they would use raw materials and machinery and labor, or one raw material instead of another, et cetera.”

“Your system, Adams—it’s

your

system, now that I’ve seen the flaws—your system wouldn’t work. The labor and raw materials would simply go to the most irresponsible and reckless managers, and the prices would be determined by the most irresponsible and reckless managers.”

“But, chief, we have already suggested removal or liquidation of the managers whose costs exceed the value of their output!”

“You are not suggesting any incentives for any manager to do the right thing, Adams, but only the most extreme penalties if he does the wrong thing. And under your system very few managers could help doing the wrong thing. Those who bid too high for their materials or labor would be removed or shot because their input exceeded their output; but those who bid too little for materials or labor would be removed or shot because they would not get enough material or labor to fill their production quotas.”

“We could

grade

the punishment, chief. We could shoot the manager for a big mistake but merely remove him for a little one.”

“All right,” said Peter sarcastically. “So if the value of a manager’s input exceeded that of his output by only 1 or 2 per cent, we would simply remove him; but if his input value exceeded his output value by 100 per cent, we would shoot him. Now, at just what percentage of excess of costs over product would you place the dividing line between removal and liquidation?”

“Maybe we could have graduated jail sentences.”

“You certainly think of the most amazing ways, Adams, of attracting managerial talent. I suppose you think all the finest young workers will be eager to draw attention to themselves as possible managers—provided, of course, they have sufficiently strong suicidal tendencies.”

Adams took a couple of pinches of snuff and paced up and down. “Suppose we abandon that whole approach.... Suppose we let the Central Planning Board set the prices?”

“How would they set them?”

“They would just guess at what the prices ought to be.”

“At what hundreds of different prices ought to be?”

Adams nodded.

“And how would they know, Adams, whether their guesses were right or wrong?”

“Well,” said Adams slowly, apparently trying to think the thing out as he paced and talked, “if the prices were right, then the results would show that the value of the output of each commodity exceeded the costs that went into producing that commodity. There would be a balance between the supply of and the demand for each commodity at those prices. But if the price set by the Central Planning Board for any raw material or machine or worker were wrong... then the result would show either that the value of the input exceeded the value of the output, or, on the other hand, that the value of the output exceeded the value of the input

by too much!”

“But how would you know what was wrong, Adams? How would you know where the mistake had occurred—if there really was a mistake? Suppose, for example, that the value of a particular output exceeded the value of a particular input ‘by too much.’ How would you know what had caused that?”

“We would know, chief, that one or more of the factors of production was underpriced.”

“And how would you know, Adams, which factor it was—whether the labor, the raw materials, the machinery, or the land? Or

which

raw material? Or

which

group of workers. Or if

several

factors were underpriced, how would you know which ones and by how much?”

Adams did not answer.

“And how would you know that the trouble

was

underpricing of the factors of production?” pursued Peter. “Might it not be just because that manager was particularly efficient, or because a particularly efficient method of production was being followed? Or merely because that commodity, relatively speaking, was being

underproduced?

And conversely, suppose that the cost of the input exceeded the value of the output? You would have the same problems in reverse. How would you know whether that result was caused by the overpricing of the factors of production, or of some particular factor, and which, and by how much—or whether the whole thing wasn’t caused by a particularly inefficient method of production or an inefficient manager?”

Again Adams was silent for a time.

“You know,” he said at length, “I’ve just thought of something. There’s a very clever Italian fellow in the Central Planning Board with whom I’ve been discussing planning problems. He’s a brilliant mathematician. He’s tremendously enthusiastic about the markets you established in consumption goods—fascinated by them. And now that I remember it, he came forward independently a few weeks ago and actually suggested setting up a system of pricing for production goods and factors of production. He claims he can work it all out by mathematics.”

“Why didn’t you tell me about him before?”

“To tell you the truth, chief, I hadn’t the slightest idea what he was driving at, at the time. I couldn’t understand his mathematics and didn’t want to admit it. And anyway, I just put him down as a sort of screwball.”

“And now?”

“Now, I’m just beginning to think that maybe I was wrong.... Not until this conversation now did I have any idea of what he may have been driving at.”

“What’s his name?”

“Baronio.”

“Let’s talk with him by all means.”

Peter glanced at his wrist watch. “I’m due to be at dinner with my father in fifteen minutes. Why not bring Baronio with you tomorrow?”

When Adams left, Sergei came in. “One of the new guards we had taken on to protect His Supremacy, Your Highness, turned out to be an agent of Bolshekov’s. He had undoubtedly been sent here to assassinate His Supremacy.”

“Where is he?”

“When our guards started to arrest him, he tried to shoot them but got shot himself. It happened in the barracks rooms just across the street. I don’t think it wise for us to publish anything about the incident—if Your Highness agrees.”

“Does His Supremacy know?”

“I thought Your Highness might not want to upset him with such knowledge.” “Very good, Sergei.” I have been given a weight of responsibility, thought Peter once more, that is just too big.

He was awake most of the night.

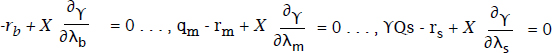

I’M afraid I can’t explain my ideas in ordinary language, Your Highness,” said Baronio, “but only in mathematical symbols. So I brought along this paper.” He was a small, eagerlooking Italian. Peter took the paper. At least half of it seemed to consist of mathematical equations, with sparse explanatory matter in between. It involved a great deal of algebra and calculus. Peter riffled through the more than fifty pages. His eye picked out a passage at random:

It may be asked if it is not possible for the Central Planning Board, in exercising the power to vary the individual γ’s subject only to the condition of Σγ = 1, to arrive at a series of γ’s, with the equivalents and the technical coefficients such that not only ΣΔθ is zero but also the single Δθ’s are zero...

In fact, the individual γ’s must be a function of the λ’s and satisfy the condition that the variation of a λ involves a variation of the γ which makes the former equal zero.

The function γ must therefore satisfy the conditions