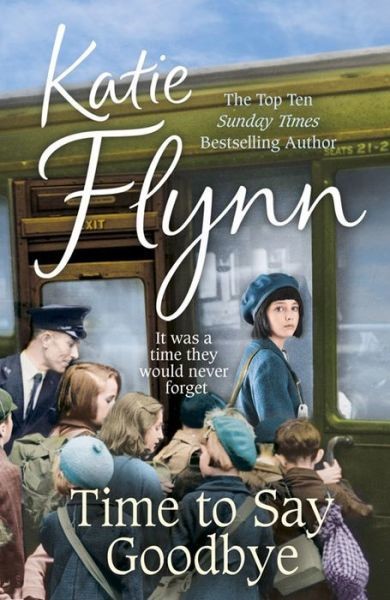

Time to Say Goodbye

Read Time to Say Goodbye Online

Authors: Katie Flynn

Contents

About the Book

It’s 1939, and three ten-year-old girls meet on a station platform.

Imogen, Rita and Debby all missed the original evacuation and now the authorities are finding it difficult to place them. When Auntie and her niece, Jill, who run the Canary and Linnet Public House, offer to take them in, the billeting officer is greatly relieved.

The countryside is heaven to the three little townies, especially after they meet Woody and Josh, also evacuees. They find that by climbing to the top of the biggest tree in the beech wood they have a perfect bird’s-eye view of the nearest RAF station and are able to watch the comings and goings of the young fighter pilots as the Battle of Britain rages. Then they find an injured flier and the war becomes a stark reality.

As they grow up, love and rivalry enter their lives and, twenty years on, when the girls decide on a reunion, many surprises come to light ...

About the Author

Katie Flynn is the author of over forty much-loved novels and has lived for many years in the north-west. A compulsive writer, she started with short stories and articles and many of her early stories were broadcast on Radio Merseyside. For the past few years, she has had to cope with ME but has continued to write.

Also available by Katie Flynn

A Liverpool Lass The Girl from Penny Lane Liverpool Taffy The Mersey Girls Strawberry Fields Rainbow’s End

Rose of Tralee No Silver Spoon Polly’s Angel

The Girl from Seaforth Sands The Liverpool Rose Poor Little Rich Girl The Bad Penny

Down Daisy Street A Kiss and a Promise Two Penn’orth of Sky A Long and Lonely Road The Cuckoo Child Darkest Before Dawn Orphans of the Storm Little Girl Lost Beyond the Blue Hills Forgotten Dreams Sunshine and Shadows Such Sweet Sorrow A Mother’s Hope In Time for Christmas Heading Home

A Mistletoe Kiss The Lost Days of Summer Christmas Wishes The Runaway

A Sixpenny Christmas The Forget-Me-Not Summer A Christmas to Remember

Available by Katie Flynn writing as Judith Saxton You Are My Sunshine First Love, Last Love Someone Special Still Waters

A Family Affair All My Fortunes Chasing Rainbows The Arcade

Harbour Hill

Sophie

Jenny Alone

Time to Say Goodbye

Katie Flynn

Dear Reader,

When I set out to write

Time To Say Goodbye

it was nothing like the book you see before you, which was meant to pick up the three youngsters, and then go to them as young women. As soon as Auntie and the Canary and Linnet entered the equation, however, they simply seized the story by the throat and everything changed.

I was evacuated to a farm in deepest Devonshire and had an idyllic four years there, scarcely aware of the war. The three girls, too, were happy, but their adventures and mine were very different and affected their growing up differently too. As so often happens when you are writing a book, the characters simply took over and dictated the story to me, for better or for worse

etc.

Whilst I was writing the book I was carried back in time and relived those far-off days and thought perhaps one day I might write the book I meant to write, using my own experience . . . but somehow there is always another book nagging to be written, so probably the one I meant to write will be put on the back burner . . .

Hope you enjoy reading this one as much as I enjoyed writing it!

All best wishes,

Katie

Chapter One

1959

THE OLD MAN

sat on the bench outside his cottage door, and stared across at the village green. Presently the bus from the market town would draw up and those still remaining on board would alight. He hoped his wife would be amongst them. As soon as she got in she would begin preparations for his dinner and already he was looking forward to what, as he grew older, was becoming the main excitement of his day. His wife was a creature of habit and he knew that on this particular day, because she had been to town, the meal would be fish of some description, mashed potatoes and a slice of jam tart for pudding. If she was in a good mood – and the bus was on time – she might make a custard. At the mere thought he felt the water come to his mouth; he was fond of custard. But even as he contemplated the meal he would presently enjoy, the bus chugged to a halt and the passengers began to descend.

He acknowledged that he was a trifle deaf but knew that his sight was still quite keen; keen enough to pick out his wife’s stumpy form and that of their next door neighbour, and several other familiar faces. One, however, was a stranger, and that was unusual enough for the old man to wipe his eyes and look harder. In recent years a modern estate of expensive houses had been built a bare couple of miles from the village but the inhabitants all had cars; had never, to his knowledge, caught a bus in their lives, so it was natural enough that the old man should stare at the young woman who descended on to the village street and looked about her. As he watched she took an uncertain step towards the general store, then seemed to change her mind and scanned the cottages in front of which the old man sat. He was still examining her face when his wife arrived at his side, and he greeted her with rather more excitement than usual.

‘Nelly, that young woman, the one what got off the bus just after you did,’ he began, but his wife, clicking with disapproval, pushed him gently through the doorway of the cottage and shut the door behind them.

‘Get inside, you silly old fool,’ she said affectionately. ‘Ha’n’t you noticed that’s starting to rain? And who’s to look after you if you get pneumonia? I didn’t notice any girl; someone from the new estate, I suppose. Nothing to do with us, you may be sure of that.’

‘I thought she looked familiar,’ he said obstinately. ‘I’m sure I’ve seen her face somewhere before, though I can’t put a name to it.’

He peered at the contents of his wife’s large wickerwork basket and saw a parcel of cod, his favourite. He poked it with a finger. ‘Is that dinner? Are you going to do white sauce to go wi’ it? And mashed taters? I’m fond of mashed taters.’

His wife laughed indulgently. ‘You’re fond of most food, and you can help by peeling the spuds,’ she said.

The old man tottered over to the sink. ‘Jam tart for afters?’ he asked eagerly, all thoughts of the stranger vanishing from his mind. ‘Oh, I do love a nice piece of jam tart!’

The young woman had been in a fever of impatience ever since she had got off the train and boarded the bus, bound for the village where she had spent a good deal of her childhood. But now, having reached her destination, she found herself feeling both shy and somewhat ill at ease. A while ago she had remembered that there was something special about a certain date in October, and had realised with a real shock that a twentieth anniversary was fast approaching. Twenty years ago three little girls had met for the first time on Lime Street station, waiting to be escorted to their new homes. They had been very different, those three little girls, but during the course of being traipsed about the country whilst the billeting officer tried to place them they had become friends, and without a word had decided that they meant, if possible, to remain together. They were from different small private schools and had missed the first wave of evacuees, and by the time they reached the village they had been worn out and desperate for somewhere they might lay their heads, though they were still determined to stay together. Others had been evacuated with their whole schools, so surely just three of them might find a home where they could be safe?

The young woman smiled reminiscently: three little girls with worn white faces, insisting upon visiting the lavatory at the back of Mrs Bailey’s shop before they would go a step further; the billeting officer in despair; and then rescue!

But she could not stand mooning here; she had a rendezvous to keep. The rain was increasing in severity and she hastily erected her umbrella and turned up the collar of her fawn mackintosh, chiding herself as she remembered that she had not wanted to be noticed. If there is one way of drawing eyes it is to stand outside in the pouring rain looking helplessly about, positively inviting attention. She must not loiter here.

Now, as she skulked beneath the umbrella’s obscuring shelter, she took a cautious peek at her surroundings. She remembered them so well, or had thought she did. She had expected many changes, for it had been a long time since she had last set foot on this stretch of pavement. She had read stories of folk returning to a childhood home and finding that everything had grown smaller, because in the eyes of a child the thatched cottages and their patches of garden had seemed huge. Yet she was unaware of any such change, and the clump of trees which surrounded the village green had seemed enormous years ago and were enormous still. She looked about her, checking on the once familiar scene, and for a moment she wondered, for there was not a soul about. But why should there be, after all? She did not have to glance at her wristwatch to know that it was only half past ten; children would be in school and adults at work, and if she stood here much longer, gaping around her like a lost soul, someone would come out of one of the cottages and ask questions. Where did she want to go? Whom had she come to see? Or worse still, they might recognise her. It was a tiny village, the sort where everyone knows everyone else’s business . . . hastily she began to walk, just as one of the women who had got off the bus glanced towards her. Ducking her head and turning it away from the bent little figure she walked straight into a puddle, a huge one, and felt it penetrate her stout brogues. She swallowed a curse and glanced quickly back, embarrassed by her own stupidity, but the old woman did not appear to have noticed. She had disappeared into her cottage, and the young woman sloshed her way out of the puddle and set off once more into the rainy morning.

In the old days the tarmac surface of the road finished within perhaps a hundred yards of the village; it used to become a lane, muddy or dusty depending on the season. But now, even allowing for the poor visibility, she could see that the tarmac stretched ahead as far as the eye could see, and as she walked the reason for this became obvious. On her left, through a discreet belt of conifers, a large housing estate had grown up. There were a great many big red brick houses with elegant driveways, double garages and gravel sweeps. Some even had forbidding wrought iron gates, though few were closed. Staring, she stepped on to the pale pink paving which divided the ordinary sidewalk from the estate. She remembered the country here as being fairly flat, but whoever had commissioned the new houses had clearly thought flatness, though useful, would not attract the right sort of buyers, and had manufactured hills and hollows around which they had landscaped the area. She peered between the branches of shielding trees, already well grown, and supposed, grudgingly, that these people – rich people – had been welcomed by the real villagers, who would have hoped that the newcomers would spend money in their small shops. And no doubt it was thanks to the housing estate that the road was both tarmacked and in good repair.

On the corner she hesitated; she could go straight ahead – now she could see that the road became the familiar lane a couple of hundred yards on – or she could take a look at the estate. Why not do just that? God knew she had plenty of time; the day stretched ahead of her, forlornly empty. Quickly, she told herself that she had always intended to explore the present village, noting changes, before the others arrived . . . if any others did arrive, that was. Suddenly, she was certain that no one would come. After all, why should they? She had noticed the date and written ahead, and receiving cautious replies had come anyway. In her heart she had hoped the others would do the same, but there was no guarantee that they would. So far as she knew, this particular October date had passed unremarked for many years.

Having decided, she made her way through the housing estate, discovering that the large and imposing houses almost hid several rows of smaller, more practical dwellings, to a point where she could see, in the distance, the opposite row of the conifers which must enclose the whole estate. Standing there in the rain, staring at the houses, she did not notice somebody coming up behind her until that someone cleared his throat, causing her to jump guiltily. She turned. He was a tall, military-looking man, with grey hair and a small bristling moustache. He was carrying a striped golfing umbrella and looked like a retired colonel, but the eyes that he turned on her were hard and cold, though his voice, when he spoke, was pleasant enough. ‘Can I help you? I expect you want Doone Avenue, or possibly Totnes Heights. People often get confused because the houses on Plymouth Road hide the more . . . practical end of the estate.’