Tiffany Girl (2 page)

Authors: Deeanne Gist

Last, other than our heroine, Flossie Jayne, and her nemesis, Nan Upton, all the Tiffany Girls depicted are based on real ones,

including their manager, Clara Driscoll. I have no idea what their temperaments were like or what they looked like, so I made all those parts up—including any words spoken by them, of course.

For more insider information, refer to my Author’s Note after the last page. But you might want to read the book first, because there are many spoilers in the Author’s Note.

PROLOGUE

R

eeve remembered everything about that morning. He remembered the scratchy wool of his short pants. His stiff collar and bow tie making it hard to swallow. The branches of the willow tree whipping against the window. The women sitting in the parlor, the air around them saturated with their homemade herbal fragrances.

But mostly he remembered his mother. So still. Lying on a table—and in the middle of the morning when everyone knew it was the time she snapped beans from the garden. Her eyes were closed, her lips turned down, her skin a funny color.

Father shifted Reeve farther up his hip. Leaning over, Reeve reached for her. Her chin was as hard as the rocks Father skipped across the creek, and as cold, too. He jerked his hand back and looked at his father in question.

Father didn’t make a sound, but tears streamed down his cheeks.

“Poor child,” someone sobbed.

Turning away, Reeve buried his face into Father’s neck, the smell of his shaving soap sharp, his neck moist from sweat, or maybe tears.

Within three months Father’s dry goods store had failed.

Within six, he’d taken Reeve to the doorstep of his grandparents’ house. Grandparents he’d never even known he had. Grandfather motioned him inside with a jerk of his head, then latched the door, cutting off the sight of Father.

Reeve stood in the entry hall, its walls bare, its air stale. Grandfather’s flinty eyes took in his mismatched stockings, his threadbare jacket, his stained hat. Reeve didn’t need to touch him to know he was hard as the rocks by the creek and just as cold.

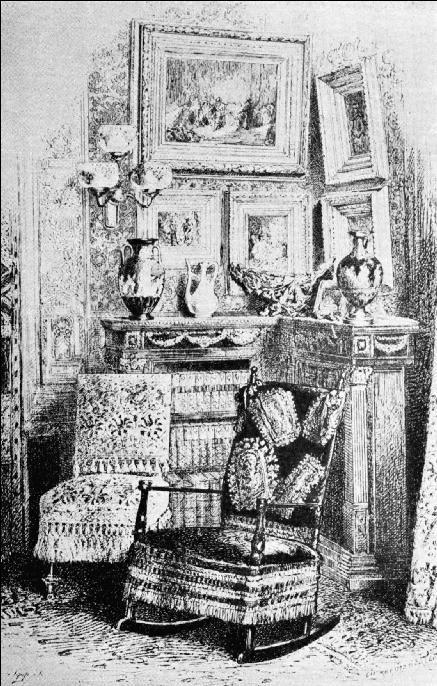

SITTING ROOM

1

“Flossie used to love this room, with its northern light and view of Stuyvesant Park. Its mauve floral walls and Baghdad rug had hosted many a happy occasion.”

CHAPTER

1

New York City, 1892

Twenty-two Years Later

Y

our father has decided to withdraw you from the School of Applied Design.”

Flossie Jayne looked up from the muslin in her hands, her fingers pausing, her needle protruding from the cream-colored fabric. “What do you mean?”

Mother secured a porcelain button to a short basque waist of a Louis Seize brocade in rich shades of burgundy and claret. The buttons had miniatures painted onto them. Miniatures Flossie had put there with her own brush.

“I mean,” Mother said, “when your current winter session at the design school is over, you will not be going back.”

Flossie lowered the bodice lining to her lap. The whalebone sandwiched between the two pieces of muslin slipped. “But, why? The painting classes won’t be complete until next summer.”

“Your father is aware of that.” She snipped the end of the thread, then picked up another button.

“Has something happened?”

Mother said nothing. Her hair was no longer as black as Flossie’s, but had softened with silver strands and was pulled up into a twist.

“Mother, I . . .

I live for those lessons. Painting is the only thing that gets me through this endless sewing.”

Even though Mother was working, she had dressed with extreme care. Her emerald gown was not as fancy as the ensembles she sewed for the upper echelons of New York society, but it was certainly nicer than that of most barber’s wives. When customers came by the house, they’d see what a fine figure she cut and would often order something similar but significantly more expensive. Thus, she and Flossie both dressed exquisitely and in the very latest fashions no matter what their plans were.

“The sewing we do is not endless,” Mother said. “Endless sewing is what those poor unfortunates in factories and sweatshops do. You and I work in our warm, cozy sitting room and handle all manner of silk, velvet, mink, lace, and jewels.”

“We sew from first light until last light, until our eyes hurt and our heads ache. We stop only to do the cooking and cleaning.” The thought of sewing without interruption was bad enough, but to give up her passion, the one thing that not only offered her a reprieve but infused her with renewed energy, was not to be borne.

“You stop every afternoon for your lessons,” Mother said.

“Which is my whole point.”

Mother

tsk

ed. “You should be happy we have the work. With so many men losing their fortunes, many seamstresses are finding themselves with fewer and fewer customers.”

“You will never lose your customers.” Flossie once again worked her needle along the edge of the whalebone, boxing it in with neat stitches. “Not when every gown you make is nothing short of a work of art.”

Mother allowed herself a small smile. “Your pieces are not far behind.”

“Even if that were true, the difference is you love to sew. I hate it. No, I loathe it. The only thing that keeps me in this chair is

knowing that if I want to attend the School of Applied Design, Papa said I’d need to bring in the income myself. But if he’s not going to let me go, then what’s the point?”

The fire in the grate popped, its heat warding off December’s chill. Flossie used to love this room, with its northern light and view of Stuyvesant Park. Its mauve floral walls and Baghdad rug had hosted many a happy occasion. The sense of warmth and well-being it once induced, however, had long since dissipated, leaving dread and drudgery in its wake, for this was where she and Mother did their work week after week, day after day.

She pushed the floor with her toe, setting her rocker in motion. “He went to the races again, didn’t he?”

Mother tied off the last button. “You really did do a lovely job painting these miniatures. Mrs. Wetmore is going to be very pleased with them.”

“How much did he lose this time?” Flossie rued the day her father had been invited to the races by one of his customers. What should have been a day of leisure ended up becoming a consuming passion. He’d even started to close the barbershop on Saturdays in order to go to the racetrack.

“It’s not for you to question how your father spends his money.”

“What about how he spends

our

money?”

“Hush.” Mother glanced at the door as if someone might hear, but they didn’t have a maid anymore, nor a cook. “You and I don’t have any money. It’s all his.”

“Why is that? We’re the ones doing the work. We’re the ones designing the clothes. We’re the ones taking care of your clients. Why don’t we get any of the money? Why do we have to hand it all over to him?”

“Because we do.”

“What if we don’t?”

“That is quite enough.”

“I

mean it, Mother. What if we simply told him no? Told him he couldn’t have it?”

Standing, Mother shook out the bodice, then held it up by its shoulders, the light glinting on its gold-braided trim. “These buttons will become more popular than they already are once the senator’s wife wears this. Perhaps tomorrow you should paint some more.”

“Let’s go on strike.”

Glancing at her sharply, Mother draped the bodice over the back of her chair. “What on earth are you talking about?”

“Let’s tell Papa we refuse to do any more work until he gives each of us a percentage of our earnings.”

Narrowing her eyes, Mother snatched up tiny scraps of fabric littering the worn oriental rug that had been in her family for generations. “You’ve been reading too many newspapers. If you’re not careful, your father will disallow it.”

“You ought to read them, too. The

New York World

gave a very detailed account of the feather curlers when they went on strike. It brought the entire feather industry to a standstill. By the end of it, night work was abolished and the women had won. Well, they’d won the first skirmish, anyway.” She scooted forward in her chair. “Don’t you see? If we both told Papa we wouldn’t work another day until he agreed to give us each a percentage of our work, he’d have no recourse but to give in to our demands.”

“No.”

“Then let’s just keep a portion and not tell him. They pay you, so he’d never know.”

Mother studied Flossie, her brown eyes catching the fire’s light. “Look around you, daughter. The rocker you are lounging in, the cup of tea at your elbow, the very walls that protect you from the cold . . . these are all a product of your father’s hard work. Surely you remember we haven’t always lived so well. It has taken him years to provide such nice things for us. If he wants to give

himself a little treat, then I will not begrudge him and neither will you.”

“I remember we lived much more modestly until you started to take in sewing. Until you discovered you had a talent—no, a gift—for creating gowns of the highest caliber. I remember Papa being so delighted that he hired a maid and then a cook so you could devote more of your time to your sewing.” She folded the muslin lining. “Everything was wonderful at first, but it was never the same after we moved here and away from all our friends. Papa opened his new shop with fancy chairs and even fancier equipment. He joined those clubs. He stayed out late. He went to the races. He fired the help.”