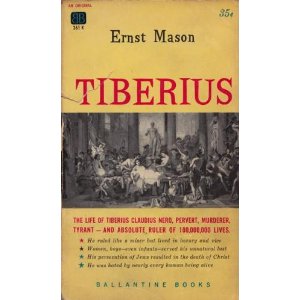

Tiberius

| Published: | 1969 |

| Tags: | Non Fiction Non Fictionttt |

Two thousand years ago, a new emperor came to the throne of Rome. His name was Tiberius Claudius Nero, and the riddle of his character has shocked and puzzled the world ever since. He used the public funds to gratify his taste for debauchery and vice, but refused to give gladiatorial contests because he was too mean to pay for them. He delighted in cruel punishments and invented ingenious new forms of torture—yet his reign was one of prosperity and peace.

Calculating and licentious, intelligent and cruel, Tiberius spent the last fourteen years of his life surrounded by hired bodyguards in his pleasure palace on Capri—one of the most hated men the world has ever known. Yet he enriched the Roman treasury by more than two billion sesterces, and the historian Mommsen has called him "the ablest of all the sovereigns the Empire

ever had.

TIBERIUS

A Panther Book

First published in the U.S.A. by Ballantine Books, Inc

PRINTING HISTORY

Ballantine edition published 1960 Panther edition published September 1961 Reprinted June 1963

Copyright © Ernst Mason 1960

For Fletcher Pratt

Conditions of Sale. This book shall nor, without the written consent of the Publishers first given, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in a

ny form of binding or cover oth

er than that in which it is published.

Printed in England by Hunt, Barnard & Co., Ltd., at the Sign of the Dolphin, Aylesbury, Bucks, and published by Hamilton & Co. (Stafford) Ltd., 108 Brampton Road, London, s.w.3

1

His name was Tiberius Claudius Nero, called Tiberius, the Emperor of one hundred million souls.

Tiberius was born into a household of tragedy. He grew up under the shadow of a greater man; he loved twice and lost twice, and when he died he was hated by nearly every human being alive. He was even hated by himself.

Tiberius spent the beginning of his life in loneliness, and most of the rest of it in running away. He feared people because he despised them. He knew that Rome was a sink, and that the great Roman Senate had become a mob of knaves and libertines; he could not, or would not, change Rome, and so he fled it. He practised foul cruelties on his enemies, and he had no friends.

As a ruler, he sacrificed morality to legality, as one commentator has said; but his "legality" was the law of the shyster. Roman law was not the equal of ours in its guarantees of personal freedom. But the

re were certain ancient, unbend

able laws which gave some protection. A man's slaves might not be made to testify against him. A virgin might not be executed for a crime. Tiberius found legal loopholes through which his desires might be exerted. Usually in preserving the letter of the law he found a path to his ends which plunged his victims into degradation and suffering worse than the thing the law protected them against.

In his personal life he was severe and sometimes unspeakable. He raped small children of both sexes; he pursued the honorable wives of Rome's great men with filthy proposals; he took a pleasure in pain. He also took great interest in literature and in the science of the day, or what passed for it—astrology and the like. He was

...

peculiar.

If Tiberius was a terror to those about him, it was an exchange that worked both ways. He was the object of a thousand plots. He was the survivor in a remorseless winnowing-out of possible successors to his stepfather, Augustus; and if he arranged the death of some of his competitors, it is also true that some of them tried to arrange his. His own wife was his enemy. Not his first wife, whom he loved and was forced to give up, but his second wife, Julia, Augustus' profligate daughter, who prostituted herself to any passer-by by night and plotted the death of her husband by day. His own mother, whose endless exertions made him Emperor in the first place, became at the last a threat to his throne. When she died he refused to give orders for her funeral until her decaying corpse was an offense to the nostrils. It was a passive, offhand sort of revenge, and thus particularly dear to Tiberius. He had done nothing. It was what he had not done that constituted the revenge.

Yet he governed well—if one applies the touchstone of "the greatest good of the greatest number." It is this that distinguishes him from a Caligula or a Nero. Under Tiberius the Empire was prosperous and at peace.

Tiberius was a pervert, a murderer, and a tyrant, but he was no fool. "He was the ablest of all the sovereigns the Empire had," says the historian Mommsen. He composed Greek verses and recited Greek epigrams. One was "After me, let fire destroy the earth!"

Caligula, Claudius, and Nero kindled the flames.

II

Tiberius died almost two thousand years ago, and of the ten billion men and women who have lived since then, nearly all have been forgotten. But we do not forget Tiberius. Even today the guides on the Isle of Capri will point out where the stooped, shambling old man hurled his victims to their death.

Tiberius was not the worst of the Roman Emperors. Caligula was mad and murderous, Nero was a terrified pervert. By our standards almost all the Caesars were in some way corrupt and strange—they might live only to kill, like Commodus, or take such queer pleasures as plucking out the body hair of their mistresses, like Domitian. Even Vespasian, one of the best, enriched himself by blackmailing his own corrupt officers.

The Caesars were not even the worst of the ancient rulers. The mist of blood and pain that hung about them was only more of what the ancient world had always known; in

Babylon, in Egypt, in all the countries that made up the world's first civilizations there had never been a time when pain and bloodshed came to a halt. But there was something about the Caesars which made them particularly fearful. Partly it was power. Partly it was something more subtle.

What set the Caesars apart was that they governed a civilized state. Rome was a Republic almost up to the time of Tiberius' birth. It is true that democracy reached only a handful—there were no rights for the slaves and very few for the poor plebeians—but that handful had rights as certain and as well established as our own. The Caesars stopped that. "I have the right to do anything at all to anyone," said Caligula to his grandmother. Roman Senators were protected by centuries of law and tradition, but a Caesar could change any law. There was only one weapon that could be used against him—assassination—and though it was many times tried it seldom succeeded. (Still, of the first twelve Emperors seven were murdered—and two more killed themselves for fear of worse.)

What made the Caesars unique among the terrible ancient rulers was that they were a step in the wrong direction. What made Tiberius unique among the Caesars was that he set the pattern for the monsters who followed.

II

Tiberius was born two thousand years ago, but Rome was already old. Five hundred years before his birth the city had more than a quarter of a million people, and the legions had already begun the victories that gave them all the Italian peninsula, all the Mediterranean, ultimately nearly all the known world. Under the centuries of the Republic Rome grew powerful and rich. More than that, the upper classes, at any rate, were free. Freedom was a new invention at that stage in the world's history. The Greeks had had it, but scaled down to midget size; their tiny cities could not compare with Rome's immensity. Rome was big as well as free. The city's rulers were elected by vote. Foreign policy was set by the Senate. Under the Republic a man knew where he stood; his rights were a matter of constitution and law. The higher his rank the more rights he had, of course, but even the poorest free-born citizen had the assurance that if he was ruled badly or harshly, at least he was ruled by men he had helped to select.

Julius Caesar changed all that.

Caesar was an ambitious, dangerous man. He would do anything for power. The Republic did not suit him. A government should have only one head, and that head, his own. He bribed, cheated, murdered, and stole his way to power. He knew that no man could conquer the centuries-old might of the Roman Republic unless that structure had shaken itself to pieces in internal strife; he stirred up the strife. He cozened the Senate into giving him an army. He cajoled the army into taking their loyalty from Rome and giving it to him. He made conquests in Rome's name and used the treasure won in battle to buy the affections of Romans, who voted him more armies and enabled him to make more conquests. He wanted to be king, but he was wise enough to grasp the power of kingship before reaching for the name. He never did become king of Rome—the daggers of Brutus and a pack of others saw to that—but he was something more. He was an emperor, Rome's first; the tide begins with him. Romans loyal to the Republic were able to kill Julius Caesar, but the Republic itself was already dead.

The murder of Julius Caesar began the most frightful civil war of Rome's history, a war that went on for thirteen bloody years. On one side were Brutus, Casius, and the rest of the Republicans; on the other, the friends and relatives of Caesar. Mark Antony was one; Lepidus was another; a stripling named Octavian, Caesar's heir (later he chang

ed his name to Augustus, and th

at is the name we will call him now), was the third. These three were the Triumvirate, joined together to fight Caesar's assassins.

But it was not for revenge that they fought. They fought for Rome.

If Brutus and Cassiu

s won, the Republic might be re-

established; but if the Triumvirate won they would own all Rome, city and colonies.

This was

the world that Tiberius was born

into two thousand years ago.

Tiberius' mother was a beautiful girl named Livia. Even for a Roman matron she was young—she was just thirteen when Tiberius was born—but she was the wife of an important man, and herself the descendant of one of Rome's best families. So was her husband. In fact, they were cousins.

Livia was stately. Her nose had an eagle's hook, but that was a sign of beauty in Rome. She had calm, tender eyes; but, more important than beauty, she had all the Roman virtues. She was chaste, she was frugal, she was loyal. A Roman matron was supposed to run her household as efficiently as a factory foreman; indeed, a Roman home was a sort of factory, for clothes were made, cloth was spun, even furnishings were usually constructed there. Livia could do that; even when she had six hundred personal slaves, she still spent hours at the loom and could find a pilfering servant by cataloguing every scrap of cloth. A Roman matron was modest and beyond scandal—or should be; Livia really was. Even the scandal-loving Romans never accused her of adultery. Once she was the center of a real scandal—a band of Roman nudists had exposed themselves to her on the street— but she would not allow them to be punished. To her men like that were the same as statues, she said.

When she was pregnant with Tiberius she kept a hen's egg warmed between her palms, day and night. When she slept she gave it to a slave to hold. She wanted the egg to hatch, because it would be an omen; and when it did hatch, and the chick was a fine young rooster with the trace of a comb, the household rejoiced. It was a fine omen. It meant that the baby would be a boy, and the comb meant that he would achieve greatness.

While that egg was hatching, the Roman armies were moving toward each other. The Republican forces opposed the legions of the Triumvirate. They met in September of the year 42

B.C.,

at Philippi, across the Adriatic Sea. It was a great bloody match which the Triumvirs won. Cassius and Brutus died, their legions begged to be allowed to join the armies of the victors, and the last hope of the Republic perished.

Two months later, on the 16th of November, the baby Tiberius was born.

As a baby Tiberius was like any other baby. A new-born infant is only a sort of multiplied egg, and if it does show signs of individual personality at an

early age, those signs are mostl

y of interest to the parents.

But the world the baby Tiberius lived in—that was something special. In the struggle of the giants for control of the world nearly everyone was involved. Whole nations were being sold into slavery, cities were being razed, and every Roman who took a stand (most highborn Romans had to) ran the risk of finding himself executed by the other side. In this world the family of Tiberius led an athletic life.

Tiberius' father was a noble Roman named Tiberius Claudius Nero the Elder. He had been a fleet captain for Julius Caesar, a high priest of the Olympian religion under the Republic, and several times an important magistrate in Rome's city government. After the battle of Philippi he declared his loyalty to one of the members of the Triumvirate, Mark Antony; probably it seemed to him that this would help insure a peaceful life for the future, but it was only a matter of weeks before the Triumvirate began quarreling among itself. Tiberius Claudius Nero was caught in the middle. He took his wife and child and went to the town of Perugia, high in the Apennine Mountains, a siege-proof town where surely he would find peace and quiet. That was his first mistake. In the division of spoils after the battle of Philippi it was Augustus, not Mark Antony, who was given control of the whole Italian peninsula. His first move was to change the habits of such Italians as had sworn personal allegiance to Mark Antony, and Perugia was full of them. In fact Mark Antony's own brother, Lucius Antonius, had taken command of the hill town and imported parties of gladiators, supplies for many months, and all the necessaries of war. No matter. Augustus besieged the town and starved it out. When it fell, young Augustus (he was not much past twenty) did not waste a good chance to teach a lesson for reasons of compassion; he selected three hundred rebellious knights and senators and executed them in front of the altar dedicated to Julius Caesar. Tiberius' father was not among them; he was already on his way to Naples, where he tried to stir up a revolt against Augustus. That didn't work either; the little family barely escaped from Naples, skulking away at night. The baby Tiberius' crying, as they leaped for a ship, nearly cost them their lives. One of the family's intimates, Velleius Paterculus, was with them in their flight. There were too many of them. Paterculus killed himself to give the others a hope of getting away.

From Naples they went to Sicily, where queer old Sextus Pompey had carved out a sort of independent sea-kingdom within the Roman framework; but Augustus made peace with Sextus, and Sicily was no longer safe for Tiberius' father. From Sicily they escaped to Greece. Trouble was not through with them; in Greece they were trapped in a forest fire, and although they escaped, Livia's dress and hair were burned away.

But Augustus offered amnesty then, and Tiberius the Elder seized it gratefully. The family returned to Rome, and settled down—briefly. The baby Tiberius was then three years old, and already a veteran of more battles, sieges, and hairs-breadth escapes than the ordinary man experiences in a lifetime.