Thyroid for Dummies (11 page)

Read Thyroid for Dummies Online

Authors: Alan L. Rubin

Taking Non-Hormonal Blood Tests

Having thyroid disease does not necessarily mean that your thyroid is over-or underactive. For example, a person with thyroid inflammation or thyroid cancer could have normal levels of FT4 and TSH even though they have a thyroid problem. In this situation, blood tests other than those described in the previous section are helpful in making the correct diagnosis. This section helps you understand when these tests are necessary and how you interpret their results.

08_031727 ch04.qxp 9/6/06 10:46 PM Page 44

44

Part I: Understanding the Thyroid

Thyroid autoantibodies

Many thyroid conditions fall into the category of

autoimmune thyroid

diseases

– such as autoimmune thyroiditis (also known as chronic thyroiditis or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (see Chapter 5)), and Graves’ disease (see Chapter 6) – as they appear to result from the body rejecting its own tissue.

Under a microscope, diseased thyroid tissue contains many of the same immune cells that are found when a foreign invader is present in the body, for example when an organ is transplanted from one person to another.

The tissue, cell, or chemical that the body is trying to reject is known as an

antigen

. One of the types of special proteins that the body manufactures to reject an antigen is called an

antibody

. When an antibody is directed against your own tissue, it is called an

autoantibody

(an antibody directed against yourself).

When you have an autoimmune thyroid disease, many autoantibodies are found in your body, but the two principal ones are called

antithyroglobulin

autoantibody

and

antimicrosomal

(now called

thyroid peroxidase

)

autoantibody

.

Antiperoxidase autoantibodies are found more often than antithyroglobulin autoantibodies. One other autoantibody is also important in people who have hyperthyroidism. This autoantibody is the thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) that acts like TSH in stimulating the thyroid to make and release more hormones.

If your doctor wants to confirm a diagnosis of an autoimmune thyroid disease, he orders tests to look for antithyroid autoantibodies and thyroid peroxidase autoantibodies. If either test returns at a level of over 100 international units per millilitre, the diagnosis is confirmed.

These autoantibodies are found at the highest levels in people with a condition called

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

(which Chapter 5 explains in more detail), but they are also found in people with

Graves’ disease

, a form of hyperthyroidism (see Chapter 6). Interestingly, thyroid autoantibodies are found at lower levels in up to 10 per cent of normal people (the percentage increases with age). Some thyroid specialists even believe that people with low levels of autoantibodies actually have subclinical (non-symptomatic) thyroid disease.

If this belief is true, the population with thyroid disease is far greater than previously thought.

If autoantibodies are not present in abnormal amounts, a diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is not appropriate.

Although each autoimmune disease of the thyroid is discussed in its own chapter in this book, the diseases are really just different clinical presentations 08_031727 ch04.qxp 9/6/06 10:46 PM Page 45

Chapter 4: Testing Your Thyroid

45

of the same underlying condition. The evidence for this statement is based on the following facts:

ߜ The thyroid tissue appears the same in the different conditions.

ߜ Autoimmune thyroid disease runs in families.

ߜ One person may pass through Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s disease, and hypothyroidism at different times.

ߜ The same types of autoantibodies are found in all three groups.

Some autoantibodies stimulate the thyroid, while others suppress the thyroid.

At any given time, the condition of someone with an autoimmune disease of the thyroid depends upon which group of antibodies is present at the highest levels. When more suppression than stimulation is present, the person has low thyroid function. When more stimulation than suppression is present, the person has hyperthyroidism. Someone may start with an overactive thyroid gland due to excess stimulation by autoantibodies, go back to normal, and then end up with low thyroid function due to over suppression. Treatment sometimes does nothing more than speed up this process.

Finding autoantibodies is a clue that thyroid disease is likely in the future.

Relatives of people with an autoimmune thyroid disease often have autoantibodies themselves, and many of them go on to develop thyroid disease at some point in their life.

In up to 25 per cent of people with an autoimmune thyroid disease, the condition goes away after a time. A higher concentration of autoantibodies does not mean that a patient is sicker than someone who has a lower concentration. This state may simply mean that the illness is less likely to go away.

Serum thyroglobulin

Thyroglobulin

is the form in which thyroid hormones are packaged within the thyroid, and this complex of hormone bound to protein occupies most of the centre of each thyroid follicle (refer to Chapter 3). Thyroglobulin is broken down to release thyroid hormones when more is needed. Thyroglobulin is found in the blood of normal individuals, but its level is much higher when thyroid damage is present (for example, with cancer of the thyroid or inflammation of the thyroid). A normal level of thyroglobulin varies from laboratory to laboratory but is typically between 3 and 42 µg/L (micrograms per litre).

Doctors don’t test the level of thyroglobulin in your blood for the purpose of making a diagnosis, because several different conditions cause elevations.

Rather, this test is used to follow the course of a person already diagnosed 08_031727 ch04.qxp 9/6/06 10:46 PM Page 46

46

Part I: Understanding the Thyroid

Theories explaining autoantibody production

Exactly why the body forms antibodies against

Another suggestion is that a foreign invader

its own tissue is not known, but several theories

(like a virus) may have antigens similar to those

exist. Ordinarily, cells in the body are present to

found in thyroid tissue. In making antibodies to

prevent production of antibodies against the

fight this foreign invader, and its foreign anti-

self. One suggestion is that people who form

gens, the body may accidentally make antibod-

thyroid autoantibodies are deficient in those

ies that fight its own tissue as well.

protective cells at some point early in life.

with a thyroid condition – especially someone with thyroid cancer, who shows an increase in thyroglobulin if their cancer grows and spreads. Immediately after surgery for thyroid cancer, the thyroglobulin level is very low, but if the cancer remains present and spreads, the thyroglobulin increases, providing a useful monitoring tool.

Determining the Size, Shape,

and Content of Your Thyroid

As discussed earlier in this chapter, levels of free thyroxine (FT4) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) are normal in people who have thyroid conditions where hormone activity is normal. Therefore, other types of test are necessary to gather information about the size, shape, and content of your thyroid gland.

And, when your doctor diagnoses abnormal thyroid activity, one or more of these studies may help to identify the underlying cause. Each test is easy and painless and provides information that is unobtainable in any other way.

Radioactive iodine uptake and scan

Your thyroid concentrates iodine from your blood in order to make thyroid hormones, scooping up so much that it boasts the richest concentration of iodine in your body (refer to Chapter 3). This concentration makes a ready target for studying the dynamic activity of this important gland.

If someone receives

radioactive iodine

(in the form of a capsule to swallow) and a device such as a Geiger counter is passed over the thyroid gland that

08_031727 ch04.qxp 9/6/06 10:46 PM Page 47

Chapter 4: Testing Your Thyroid

47

device can accurately count the level of radioactivity present. These counts of radioactivity are registered on paper as dots, giving the radiologist a useful join-the-dots puzzle for his coffee break. A normal thyroid appears like a butterfly at the lower end of the neck (refer to Chapter 3). If the gland is functioning normally, dots in every part of the gland are uniform and the picture on paper shows the shape and two-dimensional size of the gland.

If a single thyroid nodule is present, and is overactive, most of the radioactive iodine concentrates in that nodule, giving it a darker appearance on paper.

Because of this appearance, that spot of the thyroid is called a

hot nodule

.

The rest of the gland is often suppressed and appears lighter; therefore it’s said to be ‘cold’. If the nodule itself does not concentrate as much iodine as the rest of the gland, it’s called a

cold nodule

. Thyroid cancers are generally

‘cold’, because cancerous parts of the thyroid do not produce thyroid hormone in the usual way. However, most cold nodules are not cancer.

In addition to showing the size and shape of the gland, a radioactive scan and uptake measures the relative activity of the thyroid. When the thyroid is overactive, it takes up more iodine than normal. When the thyroid is underactive, it takes up less than normal. The maximum uptake of radioactivity usually occurs about 24 hours after swallowing the iodine. At this point, a normal thyroid has taken up between 5 and 25 per cent of the administered dose of iodine. An overactive thyroid takes up 35 per cent or more. An uptake between 25 and 35 per cent is a borderline reading.

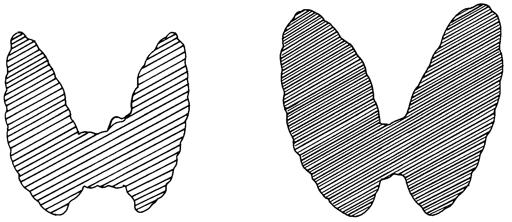

Figure 4-1 shows the appearance of a normal thyroid scan and a scan that indicates hyperthyroidism. The second scan is much darker and shows a larger thyroid gland, consistent with the increased uptake and growth of the thyroid in hyperthyroidism.

Figure 4-1:

A normal

thyroid

and a

hyperactive

thyroid as

shown in a

radioactive

iodine scan.

Normal

Hyperthyroid

08_031727 ch04.qxp 9/6/06 10:46 PM Page 48

48

Part I: Understanding the Thyroid

A few situations can arise that affect the results of a thyroid scan and uptake.

Someone taking large amounts of iodine – for example if taking a drug which contains iodine, such as amiodarone – causes both the iodine uptake within the thyroid to be blocked and dilutes the administered dose. Taking thyroid replacement hormone also blocks thyroid activity and reduces the uptake of radioactive iodine. Diseases, such as silent thyroiditis (see Chapter 12) where the iodine leaves the thyroid rapidly, also prevent a proper study.

The radioactive iodine scan and uptake generally used to be carried out to diagnose an overactive thyroid. The test is now uncommon as the blood levels of T4 and TSH are usually definitive and, along with the physical examination, are enough to confirm the diagnosis. The scan and uptake is now used more often to establish whether a thyroid that’s abnormal in shape contains multiple nodules (see Chapter 9) and to determine whether any of those nodules is overactive.

Rather than swallowing radioactive iodine by mouth, an alternative is to receive an injection of radioactive technetium, directly into a vein, 30 minutes before the scan.

Thyroid ultrasound

The

thyroid ultrasound

, also known as an

echogram

or

sonogram

, is a study that uses sound to measure the size, shape, and consistency of thyroid tissue. No radiation is used in an ultrasound study.

During this test, you lie on your back on a table with your neck hyperextended (chin right up in the air as far as you can). A gel is placed on the neck to help the transmission of sound waves. A device called a

transducer

is then passed over the area of the thyroid, sending out high-pitched sound waves that are reflected back by your tissues and collected via a microphone. Tissue that contains water gives the best reflections, while solid tissue like bone gives poor reflections.

A thyroid ultrasound can measure the size of your thyroid and any nodules very precisely. This test is used to follow treatment for an enlarged thyroid or nodule to see whether it’s shrinking. The ultrasound can also tell the difference between a cyst that is filled with fluid (and is almost never a cancer) and a solid nodule, which is sometimes a cancer.

This test is often used after a radioactive iodine scan detects an area that is cold. Is the area cold because it contains no thyroid tissue (which is how a cyst appears), or is the area cold because it contains cancerous thyroid tissue that is solid? The ultrasound can differentiate a cyst from a solid mass but cannot tell you whether the mass is cancer. (Most of the time, cancer is not present.) Figure 4-2 shows a normal ultrasound study of the thyroid and one with a prominent nodule that is solid.