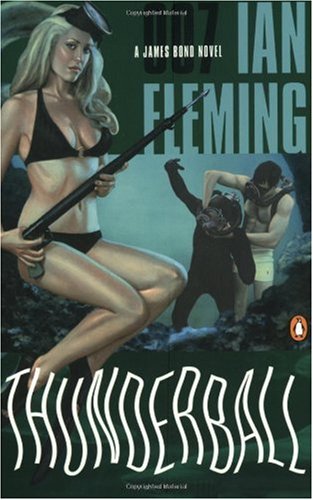

Thunderball

Authors: Ian Fleming

Tags: #Fiction, #Espionage, #Spy Adventure, #James Bond (Fictitious character)

Thunderball

1.

"Take It Easy, Mr. Bond''

It was one of those days when it seemed to James Bond that all life, as someone put it, was nothing but a heap of six to four against.

To begin with he was ashamed of himself--a rare state of mind. He had a hangover, a bad one, with an aching head and stiff joints. When he coughed--smoking too much goes with drinking too much and doubles the hangover--a cloud of small luminous black spots swam across his vision like amoebae in pond water. The one drink too many signals itself unmistakably. His final whisky and soda in the luxurious flat in Park Lane had been no different from the ten preceding ones, but it had gone down reluctantly and had left a bitter taste and an ugly sensation of surfeit. And, although he had taken in the message, he had agreed to play just one more rubber. Five pounds a hundred as it's the last one? He had agreed. And he had played the rubber like a fool. Even now he could see the queen of spades, with that stupid Mona Lisa smile on her fat face, slapping triumphantly down on his knave--the queen, as his partner had so sharply reminded him, that had been so infallibly marked with South, and that had made the difference between a grand slam redoubled (drunkenly) for him, and four hundred points above the line for the opposition. In the end it had been a twenty-point rubber, £100 against him--important money.

Again Bond dabbed with the bloodstained styptic pencil at the cut on his chin and despised the face that stared sullenly back at him from the mirror above the wash basin. Stupid, ignorant bastard! It all came from having nothing to do. More than a month of paper work--ticking off his number on stupid dockets, scribbling minutes that got spikier as the weeks passed, and snapping back down the telephone when some harmless section officer tried to argue with him. And then his secretary had gone down with the flu and he had been given a silly, and, worse, ugly bitch from the pool who called him "sir'' and spoke to him primly through a mouth full of fruit stones. And now it was another Monday morning. Another week was beginning. The May rain thrashed at the windows. Bond swallowed down two Phensics and reached for the Eno's. The telephone in his bedroom rang. It was the loud ring of the direct line with Headquarters.

James Bond, his heart thumping faster than it should have done, despite the race across London and a fretful wait for the lift to the eighth floor, pulled out the chair and sat down and looked across into the calm, gray, damnably clear eyes he knew so well. What could he read in them?

"Good morning, James. Sorry to pull you along a bit early in the morning. Got a very full day ahead. Wanted to fit you in before the rush.''

Bond's excitement waned minutely. It was never a good sign when M addressed him by his Christian name instead of by his number. This didn't look like a job--more like something personal. There was none of the tension in M's voice that heralded big, exciting news. M's expression was interested, friendly, almost benign. Bond said something noncommittal.

"Haven't seen much of you lately, James. How have you been? Your health, I mean.'' M picked up a sheet of paper, a form of some kind, from his desk, and held it as if preparing to read.

Suspiciously, trying to guess what the paper said, what all this was about, Bond said, "I'm all right, sir.''

M said mildly, "That's not what the M.O. thinks, James. Just had your last Medical. I think you ought to hear what he has to say.''

Bond looked angrily at the back of the paper. Now what the hell! He said with control, "Just as you say, sir.''

M gave Bond a careful, appraising glance. He held the paper closer to his eyes. " `This officer,' '' he read, " `remains basically physically sound. Unfortunately his mode of life is not such as is likely to allow him to remain in this happy state. Despite many previous warnings, he admits to smoking sixty cigarettes a day. These are of a Balkan mixture with a higher nicotine content than the cheaper varieties. When not engaged upon strenuous duty, the officer's average daily consumption of alcohol is in the region of half a bottle of spirits of between sixty and seventy proof. On examination, there continues to be little definite sign of deterioration. The tongue is furred. The blood pressure a little raised at 160/90. The liver is not palpable. On the other hand, when pressed, the officer admits to frequent occipital headaches and there is spasm in the trapezius muscles and so-called `fibrositis' nodules can be felt. I believe these symptoms to be due to this officer's mode of life. He is not responsive to the suggestion that over-indulgence is no remedy for the tensions inherent in his professional calling and can only result in the creation of a toxic state which could finally have the effect of reducing his fitness as an officer. I recommend that No. 007 should take it easy for two to three weeks on a more abstemious regime, when I believe he would make a complete return to his previous exceptionally high state of physical fitness.' ''

M reached over and slid the report into his OUT tray. He put his hands flat down on the desk in front of him and looked sternly across at Bond. He said, "Not very satisfactory, is it, James?''

Bond tried to keep impatience out of his voice. He said, "I'm perfectly fit, sir. Everyone has occasional headaches. Most week-end golfers have fibrositis. You get it from sweating and then sitting in a draft. Aspirin and embrocation get rid of them. Nothing to it, really, sir.''

M said severely, "That's just where you're making a big mistake, James. Taking medicine only suppresses these symptoms of yours. Medicine doesn't get to the root of the trouble. It only conceals it. The result is a more highly poisoned condition which may become chronic disease. All drugs are harmful to the system. They are contrary to nature. The same applies to most of the food we eat--white bread with all the roughage removed, refined sugar with all the goodness machined out of it, pasteurized milk which has had most of the vitamins boiled away, everything overcooked and denaturized. Why''-- M reached into his pocket for his notebook and consulted it--"do you know what our bread contains apart from a bit of overground flour?'' M looked accusingly at Bond. "It contains large quantities of chalk, also benzol peroxide powder, chlorine gas, sal ammoniac, and alum.'' M put the notebook back in his pocket. "What do you think of that?''

Bond, mystified by all this, said defensively, "I don't eat all that much bread, sir.''

"Maybe not,'' said M impatiently. "But how much stoneground whole wheat do you eat? How much yoghurt? Uncooked vegetables, nuts, fresh fruit?''

Bond smiled. "Practically none at all, sir.''

"It's no laughing matter.'' M tapped his forefinger on the desk for emphasis. "Mark my words. There is no way to health except the natural way. All your troubles''--Bond opened his mouth to protest, but M held up his hand--"the deep-seated toxemia revealed by your Medical, are the result of a basically unnatural way of life. Ever heard of Bircher-Brenner, for instance? Or Kneipp, Preissnitz, Rikli, Schroth, Gossman, Bilz?''

"No, sir.''

"Just so. Well, those are the men you would be wise to study. Those are the great naturopaths--the men whose teaching we have foolishly ignored. Fortunately''--M's eyes gleamed enthusiastically--"there are a number of disciples of these men practicing in England. Nature cure is not beyond our reach.''

James Bond looked curiously at M. What the hell had got into the old man? Was all this the first sign of senile decay? But M looked fitter than Bond had ever seen him. The cold gray eyes were clear as crystal and the skin of the hard, lined face was luminous with health. Even the iron-gray hair seemed to have new life. Then what was all this lunacy?

M reached for his IN tray and placed it in front of him in a preliminary gesture of dismissal. He said cheerfully, "Well, that's all, James. Miss Moneypenny has made the reservation. Two weeks will be quite enough to put you right. You won't know yourself when you come out. New man.''

Bond looked across at M, aghast. He said in a strangled voice, "Out of where, sir?''

"Place called Shrublands. Run by quite a famous man in his line--Wain, Joshua Wain. Remarkable chap. Sixty-five. Doesn't look a day over forty. He'll take good care of you. Very up-to-date equipment, and he's even got his own herb garden. Nice stretch of country. Near Washington in Sussex. And don't worry about your work here. Put it right out of your mind for a couple of weeks. I'll tell 009 to take care of the Section.''

Bond couldn't believe his ears. He said, "But, sir. I mean, I'm perfectly all right. Are you sure? I mean, is this really necessary?''

"No.'' M smiled frostily. "Not necessary. Essential. If you want to stay in the double-O Section, that is. I can't afford to have an officer in that section who isn't one-hundred-per-cent fit.'' M lowered his eyes to the basket in front of him and took out a signal file. "That's all, 007.'' He didn't look up. The tone of voice was final.

Bond got to his feet. He said nothing. He walked across the room and let himself out, closing the door with exaggerated softness. Outside, Miss Moneypenny looked sweetly up at him. Bond walked over to her desk and banged his fist down so that the typewriter jumped. He said furiously, "Now what the hell, Penny?

Has the old man gone off his rocker? What's all this bloody nonsense? I'm damned if I'm going. He's absolutely nuts.''

Miss Moneypenny smiled happily. "The manager's been terribly helpful and kind. He says he can give you the Myrtle room, in the annex. He says it's a lovely room. It looks right over the herb garden. They've got their own herb garden, you know.''

"I know all about their bloody herb garden. Now look here, Penny,'' Bond pleaded with her, "be a good girl and tell me what it's all about. What's eating him?''

Miss Moneypenny, who often dreamed hopelessly about Bond, took pity on him. She lowered her voice conspiratorially. "As a matter of fact, I think it's only a passing phase. But it is rather bad luck on you getting caught up in it before it's passed. You know he's always apt to get bees in his bonnet about the efficiency of the Service. There was the time when all of us had to go through that physical-exercise course. Then he had that head-shrinker in, the psychoanalyst man--you missed that. You were somewhere abroad. All the Heads of Section had to tell him their dreams. He didn't last long. Some of their dreams must have scared him off or something. Well, last month M got lumbago and some friend of his at Blades, one of the fat, drinking ones I suppose''--Miss Moneypenny turned down her desirable mouth--"told him about this place in the country. This man swore by it. Told M that we were all like motor cars and that all we needed from time to time was to go to a garage and get decarbonized. He said he went there every year. He said it only cost twenty guineas a week, which was less than what he spent in Blades in one day, and it made him feel wonderful. Well, you know M always likes trying new things, and he went there for ten days and came back absolutely sold on the place. Yesterday he gave me a great talking-to all about it and this morning in the post I got a whole lot of tins of treacle and wheat germ and heaven knows what all. I don't know what to do with the stuff. I'm afraid my poor poodle'll have to live on it. Anyway, that's what's happened and I must say I've never seen him in such wonderful form. He's absolutely rejuvenated.''

"He looked like that blasted man in the old Kruschen Salts advertisements. But why does he pick on me to go to this nuthouse?''

Miss Moneypenny gave a secret smile. "You know he thinks the world of you--or perhaps you don't. Anyway, as soon as he saw your Medical he told me to book you in.'' Miss Moneypenny screwed up her nose. "But, James, do you really drink and smoke as much as that? It can't be good for you, you know.'' She looked up at him with motherly eyes.

Bond controlled himself. He summoned a desperate effort at nonchalance, at the throw-away phrase. "It's just that I'd rather die of drink than of thirst. As for the cigarettes, it's really only that I don't know what to do with my hands.'' He heard the stale, hangover words fall like clinker in a dead grate. Cut out the schmaltz! What you need is a double brandy and soda.

Miss Moneypenny's warm lips pursed into a disapproving line. "About the hands--that's not what I've heard.''

"Now don't you start on me, Penny.'' Bond walked angrily toward the door. He turned round. "Any more ticking-off from you and when I get out of this place I'll give you such a spanking you'll have to do your typing off a block of Dunlopillo.''

Miss Moneypenny smiled sweetly at him. "I don't think you'll be able to do much spanking after living on nuts and lemon juice for two weeks, James.''

Bond made a noise between a grunt and a snarl and stormed out of the room.

2.

Shrublands

James Bond slung his suitcase into the back of the old chocolate-brown Austin taxi and climbed into the front seat beside the foxy, pimpled young man in the black leather windcheater. The young man took a comb out of his breast pocket, ran it carefully through both sides of his duck-tail haircut, put the comb back in his pocket, then leaned forward and pressed the self-starter. The play with the comb, Bond guessed, was to assert to Bond that the driver was really only taking him and his money as a favor. It was typical of the cheap self-assertiveness of young labor since the war. This youth, thought Bond, makes about twenty pounds a week, despises his parents, and would like to be Tommy Steele. It's not his fault. He was born into the buyers' market of the Welfare State and into the age of atomic bombs and space flight. For him, life is easy and meaningless. Bond said, "How far is it to Shrublands?''

The young man did an expert but unnecessary racing change round an island and changed up again. " 'Bout half an hour.'' He put his foot down on the accelerator and neatly but rather dangerously overtook a lorry at an intersection.

"You certainly get the most out of your Bluebird.''

The young man glanced sideways to see if he was being laughed at. He decided that he wasn't. He unbent fractionally. "My dad won't spring me something better. Says this old crate was okay for him for twenty years so it's got to be okay for me for another twenty. So I'm putting money by on my own. Halfway there already.''

Bond decided that the comb play had made him over-censorious. He said, "What are you going to get?''

"Volkswagen Minibus. Do the Brighton races.''

"That sounds a good idea. Plenty of money in Brighton.''

"I'll say.'' The young man showed a trace of enthusiasm. "Only time I ever got there, a couple of bookies had me take them and a couple of tarts to London. Ten quid and a fiver tip. Piece of cake.''

"Certainly was. But you can get both kinds at Brighton. You want to watch out for being mugged and rolled. There are some tough gangs operating out of Brighton. What's happened to The Bucket of Blood these days?''

"Never opened up again after that case they had. The one that got in all the papers.'' The young man realized that he was talking as if to an equal. He glanced sideways and looked Bond up and down with a new interest. "You going into the Scrubs or just visiting?''

"Scrubs?''

"Shrublands--Wormwood Scrubs--Scrubs,'' said the young man laconically. "You're not like the usual ones I get to take there. Mostly fat women and old geezers who tell me not to drive so fast or it'll shake up their sciatica or something.''

Bond laughed. "I've got fourteen days without the option. Doctor thinks it'll do me good. Got to take it easy. What do they think of the place round here?''

The young man took the turning off the Brighton road and drove westward under the Downs through Poynings and Fulking. The Austin whined stolidly through the inoffensive countryside. "People think they're a lot of crackpots. Don't care for the place. All those rich folk and they don't spend any money in the area. Tearooms make a bit out of them--specially out of the cheats.'' He looked at Bond. "You'd be surprised. Grown people, some of them pretty big shots in the City and so forth, and they motor around in their Bentleys with their bellies empty and they see a tea shop and go in just for their cups of tea. That's all they're allowed. Next thing, they see some guy eating buttered toast and sugar cakes at the next table and they can't stand it. They order mounds of the stuff and hog it down just like kids who've broken into the larder--looking round all the time to see if they've been spotted. You'd think people like that would be ashamed of themselves.''

"Seems a bit silly when they're paying plenty to take the cure or whatever it is.''

"And that's another thing.'' The young man's voice was indignant. "I can understand charging twenty quid a week and giving you three square meals a day, but how do they get away with charging twenty quid for giving you nothing but hot water to eat? Doesn't make sense.'' "I suppose there are the treatments. And it must be worth it to the people if they get well.''

"Guess so,'' said the young man doubtfully. "Some of them do look a bit different when I come to take them back to the station.'' He sniggered. "And some of them change into real old goats after a week of nuts and so forth. Guess I might try it myself one day.'' "What do you mean?''

The young man glanced at Bond. Reassured and remembering Bond's worldly comments on Brighton, he said, "Well, you see we got a girl here in Washington. Racy bird. Sort of local tart, if you see what I mean. Waitress at a place called The Honey Bee Tea Shop-- or was, rather. She started most of us off, if you get my meaning. Quid a go and she knows a lot of French tricks. Regular sport. Well, this year the word got round up at the Scrubs and some of these old goats began patronizing Polly--Polly Grace, that's her name. Took her out in their Bentleys and gave her a roll in a deserted quarry up on the Downs. That's been her pitch for years. Trouble was they paid her five, ten quid and she soon got too good for the likes of us. Priced her out of our market, so to speak. Inflation, sort of. And a month ago she chucked up her job at The Honey Bee, and you know what?'' The young man's voice was loud with indignation. "She bought herself a beat-up Austin Metropolitan for a couple of hundred quid and went mobile. Just like the London tarts in Curzon Street they talk about in the papers. Now she's off to Brighton, Lewes--anywhere she can find the sports, and in between whiles she goes to work in the quarry with these old goats from the Scrubs! Would you believe it!'' The young man gave an angry blast on his klaxon at an inoffensive couple on a tandem bicycle.

Bond said seriously, "That's too bad. I wouldn't have thought these people would be interested in that sort of thing on nut cutlets and dandelion wine or whatever they get to eat at this place.''

The young man snorted. "That's all you know. I mean''--he felt he had been too emphatic--"that's what we all thought. One of my pals, he's the son of the local doctor, talked the thing over with his dad-- in a roundabout way, sort of. And his dad said no. He said that this sort of diet and no drink and plenty of rest, what with the massage and the hot and cold sitz baths and what have you, he said that all clears the blood stream and tones up the system, if you get my meaning. Wakes the old goats up--makes 'em want to start cutting the mustard again, if you know the song by that Rosemary Clooney.''

Bond laughed. He said, "Well, well. Perhaps there's something to the place after all.''

A sign on the right of the road said: " Shrublands. Gateway to Health. First right. Silence please. '' The road ran through a wide belt of firs and evergreens in a fold of the Downs. A high wall appeared and then an imposing, mock-battlemented entrance with a Victorian lodge from which a thin wisp of smoke rose straight up among the quiet trees. The young man turned in and followed a gravel sweep between thick laurel bushes. An elderly couple cringed off the drive at a blare from his klaxon and then on the right there were broad stretches of lawn and neatly flowered borders and a sprinkling of slowly moving figures, alone and in pairs, and behind them a redbrick Victorian monstrosity from which a long glass sun parlor extended to the edge of the grass.

The young man pulled up beneath a heavy portico with a crenelated roof. Beside a varnished, iron-studded arched door stood a tall glazed urn above which a notice said: " No smoking inside. Cigarettes here please. '' Bond got down from the taxi and pulled his suitcase out of the back. He gave the young man a ten-shilling tip. The young man accepted it as no less than his due. He said, "Thanks. You ever want to break out, you can call me up. Polly's not the only one. And there's a tea shop on the Brighton road has buttered muffins. So long.'' He banged the gears into bottom and ground off back the way he had come. Bond picked up his suitcase and walked resignedly up the steps and through the heavy door.

Inside it was very warm and quiet. At the reception desk in the big oak-paneled hall a severely pretty girl in starched white welcomed him briskly. When he had signed the register she led him through a series of somberly furnished public rooms and down a neutral-smelling white corridor to the back of the building. Here there was a communicating door with the annex, a long, low, cheaply built structure with rooms on both sides of a central passage. The doors bore the names of flowers and shrubs. She showed him into Myrtle, told him that "the Chief'' would see him in an hour's time, at six o'clock, and left him. It was a room-shaped room with furniture-shaped furniture and dainty curtains. The bed was provided with an electric blanket. There was a vase containing three marigolds beside the bed and a book called Nature Cure Explained by Alan Moyle, M.N.B.A. Bond opened it and ascertained that the initials stood for "Member: British Naturopathic Association.'' He turned off the central heating and opened the windows wide. The herb garden, row upon row of small nameless plants round a central sundial, smiled up at him. Bond unpacked his things and sat down in the single armchair and read about eliminating the waste products from his body. He learned a great deal about foods he had never heard of, such as Potassium Broth, Nut Mince, and the mysteriously named Unmalted Slippery Elm. He had got as far as the chapter on massage and was reflecting on the injunction that this art should be divided into Effleurage, Stroking, Friction, Kneading, Petrissage, Tapotement, and Vibration, when the telephone rang. A girl's voice said that Mr. Wain would be glad to see him in Consulting Room A in five minutes.

Mr. Joshua Wain had a firm, dry handshake and a resonant, encouraging voice. He had a lot of bushy gray hair above an unlined brow, soft, clear brown eyes, and a sincere and Christian smile. He appeared to be genuinely pleased to see Bond and to be interested in him. He wore a very clean smocklike coat with short sleeves from which strong hairy arms hung relaxed. Below were rather incongruous pin-stripe trousers. He wore sandals over socks of conservative gray and when he moved across the consulting room his stride was a springy lope.

Mr. Wain asked Bond to remove all his clothes except his shorts. When he saw the many scars he said politely, "Dear me, you do seem to have been in the wars, Mr. Bond.''

Bond said indifferently, "Near miss. During the war.''

"Really! War between peoples is a terrible thing. Now, just breathe in deeply, please.'' Mr. Wain listened at Bond's back and chest, took his blood pressure, weighed him and recorded his height, and then, after asking him to lie face down on a surgical couch, handled his joints and vertebrae with soft, probing fingers.

While Bond replaced his clothes, Mr. Wain wrote busily at his desk. Then he sat back. "Well, Mr. Bond, nothing much to worry about here, I think. Blood pressure a little high, slight osteopathic lesions in the upper vertebrae--they'll probably be causing your tension headaches, by the way--and some right sacroiliac strain with the right ilium slightly displaced backwards. Due to a bad fall some time, no doubt.'' Mr. Wain raised his eyebrows for confirmation.

Bond said, "Perhaps.'' Inwardly he reflected that the "bad fall'' had probably been when he had had to jump from the Arlberg Express after Heinkel and his friends had caught up with him around the time of the Hungarian uprising in 1956.

"Well, now.'' Mr. Wain drew a printed form toward him and thoughtfully ticked off items on a list. "Strict dieting for one week to eliminate the toxins in the blood stream. Massage to tone you up, irrigation, hot and cold sitz baths, osteopathic treatment, and a short course of traction to get rid of the lesions. That should put you right. And complete rest, of course. Just take it easy, Mr. Bond. You're a civil servant, I understand. Do you good to get away from all that worrying paper work for a while.'' Mr. Wain got up and handed the printed form to Bond. "Treatment rooms in half an hour, Mr. Bond. No harm in starting right away.''

"Thank you.'' Bond took the form and glanced at it. "What's traction, by the way?''

"A mechanical device for stretching the spine. Very beneficial.'' Mr. Wain smiled indulgently. "Don't be worried by what some of the other patients tell you about it. They call it `The Rack.' You know what wags some people are.''

"Yes.''

Bond walked out and along the white-painted corridor. People were sitting about, reading or talking in soft tones in the public rooms. They were all elderly, middle-class people, mostly women, many of whom wore unattractive quilted dressing gowns. The warm, close air and the frumpish women gave Bond claustrophobia. He walked through the hall to the main door and let himself out into the wonderful fresh air.

Bond walked thoughtfully down the trim narrow drive and smelled the musty smell of the laurels and the laburnums. Could he stand it? Was there any way out of this hell-hole short of resigning from the Service? Deep in thought, he almost collided with a girl in white who came hurrying round a sharp bend in the thickly hedged drive. At the same instant as she swerved out of his path and flashed him an amused smile, a mauve Bentley, taking the corner too fast, was on top of her. At one moment she was almost under its wheels, at the next, Bond, with one swift step, had gathered her up by the waist and, executing a passable Veronica, with a sharp swivel of his hips had picked her body literally off the hood of the car. He put the girl down as the Bentley dry-skidded to a stop in the gravel. His right hand held the memory of one beautiful breast. The girl said, "Oh!'' and looked up into his eyes with an expression of flurried astonishment. Then she took in what had happened and said breathlessly, "Oh, thank you.'' She turned toward the car.

A man had climbed unhurriedly down from the driving seat. He said calmly, "I am so sorry. Are you all right?'' Recognition dawned on his face. He said silkily, "Why, if it isn't my friend Patricia. How are you, Pat? All ready for me?''

The man was extremely handsome--a dark-bronzed woman-killer with a neat mustache above the sort of callous mouth women kiss in their dreams. He had regular features that suggested Spanish or South American blood and bold, hard brown eyes that turned up oddly, or, as a woman would put it, intriguingly, at the corners. He was an athletic-looking six foot, dressed in the sort of casually well-cut beige herring-bone tweed that suggests Anderson and Sheppard. He wore a white silk shirt and a dark red polka-dot tie, and the soft dark brown V-necked sweater looked like vicuna. Bond summed him up as a good-looking bastard who got all the women he wanted and probably lived on them--and lived well.