Throw Them All Out (10 page)

Read Throw Them All Out Online

Authors: Peter Schweizer

Redeveloping a military base using taxpayer money to boost your investment is of course a benefit, personal and financial: Gregg was able to put his thumb on the scale of fair-market reward for his investment. The former senator now works for Goldman Sachs as a consultant, where he provides "strategic advice" and assists "in business development initiatives."

14

Â

These kinds of deals are not at all uncommon. Congressman Ken Calvert of California is a Republican member of the powerful Appropriations Committee and was first elected to Congress in 1992. His background is in real estate, and through a real estate firm he partly owns, run by his brother Quint, he is still an active investor.

In 2005, Calvert and a partner paid $550,000 for a 4.3-acre parcel of land just south of March Air Reserve Base in Southern California. Shortly afterward, he secured $1.5 million in taxpayer money to support commercial development around the base. Less than a year after the earmark, Calvert and his partner sold the land (without having made any improvements) for $985,000âa 79% profit. Not bad!

In the early summer of 2005, Calvert's real estate firm brokered a sale involving a property at 20330 Temescal Canyon Road, in Corona, California, which was a few blocks from a proposed interchange for Interstate 15. Calvert then helped secure an earmark to build the interchange. Within six months, the property was sold at a nearly $500,000 profit. Calvert's firm received a commission on both transactions. Good work if you can get it.

Calvert was careful: he sent both of these earmarks to the House Ethics Committee for approval, because he stood to benefit personally from them. The committee, in a letter signed by Congresswoman Stephanie Tubbs Jones and Congressman Alcee Hastings, said the use of taxpayer money was fine because any profits "resulting from the earmark would be incremental and indirect and would be experienced as a member of a class of landholders." In other words, Calvert was not the sole beneficiary, and the earmarked funds were not paid directly to him.

15

Congressman David Hobson of Ohio helped obtain federal earmarks to build a freight transfer center at the Columbus airport to help ship goods to and from central Ohio. The trouble is that Hobson co-owned an office building near the project, and his tenants included freight companies such as FedEx that would use the freight center. He'd bought the building in 2001, and over the next seven years secured $30 million in federal transportation money to build the freight terminal, which was part of the conversion of old Rickenbacker Air Force Base outside Columbus. On another occasion, in 2004, Hobson worked to get nearly $2 million in taxpayer money to widen a road near Dayton, which happened to run right in front of a condominium development in which he was an investor. He had bought into the project only one year earlier.

Hobson retired from office in 2008. The House Ethics Committee, at the time chaired by Congresswoman Stephanie Tubbs Jones, again said that the earmarks were acceptable because they were only an indirect benefit to Hobson and the airport investment was "speculative."

Â

Congressman Heath Shuler of North Carolina is relatively new to Congress, but he quickly demonstrated his understanding that the power of his position could be helpful in a real estate transactionâparticularly if it involved a deal with a government agency that he helped oversee.

First elected in 2006 in a western North Carolina district, Shuler had been a star quarterback at the University of Tennessee who'd had a brief stint in the NFL before becoming a real estate investor. One of his largest holdings in 2007 was in a real estate entity called the Cove at Blackberry Ridge, whose investors owned a large plot of land. According to Shuler's financial disclosures, his stake in the Cove was worth between $5 million and $25 million at the time. The investors planned to turn their land into a residential development. But there was one problem: they didn't have water access rights.

That seemed to be fixed in August 2008 when the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) announced a new water access deal for the investment group, providing 145 feet of frontage along the shoreline of the Watts Bar Reservoir in exchange for water access rights the group held in a neighboring county. What makes this so interesting is that at the time Shuler sat on the congressional subcommittee that had oversight of the TVA. When the deal was announced, eyebrows were raised. TVA employees first claimed they did not know Congressman Shuler was involved in the project. For his part, Shuler denied having any contact with the government agency. But later, he admitted that he had indeed picked up the phone and called TVA President Tom Kilgore in 2007 about getting the land-swap deal done. A TVA inspector general's report noted that there was an "inherent conflict of interest" in the swap. The report also said that Shuler's deal "created the appearance of preferential treatment." However, the report was quick to beg off any condemnation. "We make no judgment as to whether Congressman Shuler's actions connected to the Blackberry Cove matter violate any ethical standard." For its part, the House Ethics Committee again found nothing wrong.

16

Congressman Bennie Thompson, when he is not inserting earmarks for Napa Valley, California, has done so for tiny Bolton, Mississippi, population 600. One earmark was for a museum project; another, for $500,000, was to help improve the infrastructure of the Bolton Industrial Park. What Thompson hopes we don't notice is that he owns commercial real estate in the town, including lots 1, 3, and 31 on L. C. Turner Circle and what he describes as "2 acres of unimproved land in Bolton, Mississippi." It so happens that the earmarked projects are very near his investment properties.

Representative Maurice Hinchey of New York has the honor of being one of the fastest climbers in Congress in terms of net worth. In 2004, his net assets, based on his personal financial disclosure forms, totaled around $74,000. In 2008, he reported an average net worth of $727,000.

17

That's an 800% increase in just four years. How did he do it?

Much of it came through his sponsorship of an earmark for $800,000 to the Department of the Interior for water and wastewater infrastructure improvements in the Hudson Valley town of Saugerties. Specifically, it was for upgrades to Partition Street. In a press release, Hinchey took credit for bringing money to the town: "Congressman Used Position on House Appropriations Subcommittee on Interior to Obtain Funds, Which Will Help Promote Economic Growth in the Village," it read. In the release he boasted that "a second portion of the sanitary system on Route 9W or Partition Street is in the center of the business district of the Village of Saugerties."

What Hinchey didn't mention was that he owned a quarter of the land that sits under the Partition Street project, which calls for the development of a three-story, thirty-room boutique hotel with a restaurant and catering hall.

Hinchey had bought two lots there in 2004 for a combined value of between $30,000 and $100,000. As the earmarked project got under way, the value of his properties surged to

more than

five times

their original value. By the time of his 2009 financial disclosure, he listed their value as between $250,000 and $500,000. Incredulously, when asked about the project and the earmark, Hinchey said it was not a conflict of interest. He merely owns the land, he said, and has no direct involvement in the development of the property.

18

Okay. That explains it.

Â

Sometimes members of the Permanent Political Class can enhance the value of their real estate by using a third party. Congressman Jerry Lewis of California has served in the House since 1979, representing three different Southern California districts in the course of three decades (thanks to redistricting). The Republican was chairman of the House Appropriations Committee and is now a senior member of that committee.

Over the past ten years, Lewis has pushed earmarks for a private company called Environmental Systems Research Institute, to the tune of tens of millions of dollars. The firm is based in Redlands, California, and was founded by Jack and Laura Dangermond, who are campaign contributors of Lewis's. In 2001, after receiving the benefits of numerous earmarks from Lewis, the Dangermonds decided to donate 41 pristine acres of land directly across from Lewis's house as part of a scenic canyon. The donation was made to the city of Redlands, and was contingent on its never being developed. Naturally, that gift increased the property value of Lewis's home.

19

In another instance, Lewis secured a $500,000 earmark to upgrade the Barracks Row section of Capitol Hill in Washington. (Some of that money was used to plant flowers.) On the House floor, Lewis explained that he was a firm supporter of beautifying that area. What he never mentioned was that he and his wife owned a $1 million house four blocks away.

20

Â

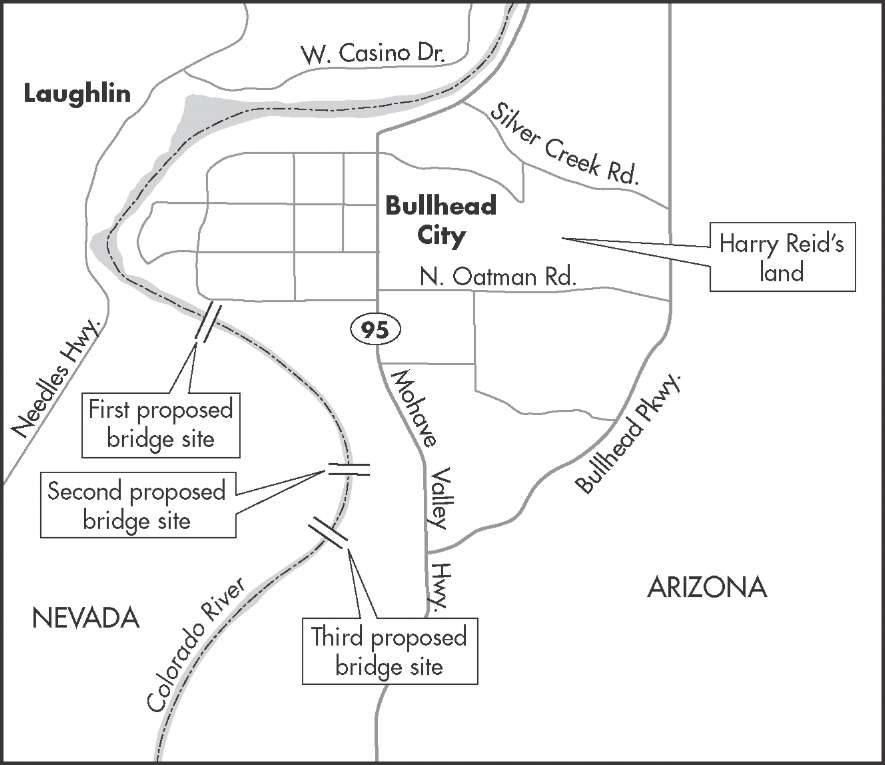

Another one of those politicians who has seen his wealth rise in recent years is Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid of Nevada. Reid doesn't trade a lot of stocks, but he does buy and trade land. And he is often able to boost the profits from his investments by the use of the power of his office. In 2005, Senator Reid sponsored an $18 million earmark to build a bridge over the Colorado River to connect Laughlin, Nevada, with Bullhead City, Arizona. (There was already one bridge connecting the two places.) Neighboring Arizona's two senators denounced the earmark as pork, and a completely unnecessary expenditure.

As it happened, a few miles from the proposed bridge there was a 160-acre parcel of land owned by, well, Harry Reid. Local officials predicted that the bridge would "undoubtedly hike land values in an already-booming commuter town, where speculators are snapping up undeveloped land for housing developments and other projects." Reid's office insisted that "Senator Reid's support for the bridge had absolutely nothing to do with property he owns."

21

Of course.

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

Â

Â

Reid has done very well with land deals over the years. In 1998, he bought undeveloped residential property just outside Las Vegas for about $400,000. In 2001, he sold it to a friend (Jay Brown, a longtime casino lawyer) for a stake in a limited liability company that held the property. Reid never reported the transaction on his financial disclosure form. By moving the property to the LLC, he could effectively shield it from future disclosures, because now the LLC was technically the owner, not him. All he had to disclose was that he had a stake in the company.

The LLC tried to get the land rezoned from residential to commercial, which would make it far more valuable, submitting its request to the appropriate subcommittee of the Clark County Zoning Commission. The answer was no: rezoning would be "inconsistent" with the Clark County Master Development Plan. (The subcommittee's no vote was 4 to 1.) Brown and Reid then took it to the full Clark County Commission. Reid's name even came up at the hearings. "Mr. Brown's partner is Harry Reid," commissioners were told.

Did I mention that at this time Clark County commissioners were trying to obtain federal earmarks for a variety of projects through Harry Reid's office? Or that Reid had funneled tens of millions of dollars in earmarks to Clark County over the years?

The commission granted the rezoning. Shortly thereafter, Reid and Brown sold the land to a shopping center developer for $1.6 million. Reid's personal take was $1.1 million.

22

Leveraging your power for a land deal is one of the best paths to honest graft. It's difficult to determine the actual market price of most properties, so disclosure statements can be murky. And when an earmarked project improves the value of the property, it can be hard to calculate just how much that new road, transit stop, or beautification added to it. But there can be little doubt that the political class is the only group of people in America who can get away with using taxpayer money to increase the value of their real estate, while declaring they are doing it in the public's interest.

CAPITALIST CRONIES

In Part One we looked at the various ways politicians use their power to get rich, or richer than they were when they entered office. The temptation to seize an opportunityâa stock tip, or the power of legislationâis pervasive. But there is a broader, more subtle motivation as well: politicians are surrounded by wealthy friends and donors who use their access to power to enrich themselves. If all of your friends are using you to get rich, wouldn't you want a piece of the action?

In Part Two we will look at the semiprivate sector: businessmen and investors who get rich through their political connections, tilting the playing field of the free market by lobbying for handouts. Just as with the insider trading and land deals in Part One, there is nothing illegal about this aspect of crony capitalism. Unfair, perhaps unethical, perhaps immoralâbut not illegal. It would take a revolution in the mindset and the rules of the game in Washington to put a stop to it. But the least we can do is pull back the curtain and bring some sunlight into the dark rooms of the crony game.