Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages (13 page)

Read Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages Online

Authors: Guy Deutscher

Tags: #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Linguistics, #Comparative linguistics, #General, #Historical linguistics, #Language and languages in literature, #Historical & Comparative

Now imagine that an anthropologist specializing in primitive cultures beams herself down to the natives in Silicon Valley, whose way of life has not advanced a kilobyte beyond the Google age and whose tools have remained just as primitive as they were in the twenty-first century. She brings along with her a tray of taste samples called the Munsell Taste System. On it are representative samples of the whole taste space, 1,024 little fruit cubes that automatically reconstitute themselves on the tray the moment one picks them up. She asks the natives to try each of these and tell her the name of the taste in their language, and she is

astonished at the abject poverty of their fructiferous vocabulary. She cannot comprehend why they are struggling to describe the taste samples, why their only abstract taste concepts are limited to the crudest oppositions such as “sweet” and “sour,” and why the only other descriptions they manage to come up with are “it’s a bit like an X,” where X is the name of a certain legacy fruit. She begins to suspect that their taste buds have not yet fully evolved. But when she tests the natives, she establishes that they are fully capable of telling the difference between any two cubes in her sample. There is obviously nothing wrong with their tongue, but why then is their langue so defective?

Let’s try to help her. Suppose you are one of those natives and she has just given you a cube that tastes like nothing you’ve ever tried before. Still, it vaguely reminds you of something. For a while you struggle to remember, then it dawns on you that this taste is slightly similar to those wild strawberries you had in a Parisian restaurant once, only this taste seems ten times more pronounced and is blended with a few other things that you can’t identify. So finally you say, very hesitantly, that “it’s a bit like wild strawberries.” Since you look like a particularly intelligent and articulate native, the anthropologist cannot resist posing a meta-question: doesn’t it feel odd and limiting, she asks, not to have precise vocabulary to describe tastes in the region of wild strawberries? You tell her that the only things “in the region of wild strawberry” that you’ve ever tasted before were wild strawberries, and that it has never crossed your mind that the taste of wild strawberries should need any more general or abstract description than “the taste of wild strawberries.” She smiles with baffled incomprehension.

If all this sounds absurd, then just replace “taste” with “color” and you’ll see that the parallel is quite close. We do not have the occasion to manipulate the taste and consistency of fruit, and we are not exposed to a systematic array of highly “saturated” (that is, pure) tastes, only to a few random tastes that occur in the fruit we happen to know. So we have not developed a refined vocabulary to describe different ranges of fruity flavor in abstraction from a particular fruit. Likewise, people in primitive cultures—as Gladstone had observed at the very beginning of

the color debate—have no occasion to manipulate colors artificially and are not exposed to a systematic array of highly saturated colors, only to the haphazard and often unsaturated colors presented by nature. So they have not developed a refined vocabulary to describe fine shades of hue. We don’t see the need to talk about the taste of a peach in abstraction from the particular object, namely a peach. They don’t see the need to talk about the color of a particular fish or bird or leaf in abstraction from the particular fish or bird or leaf. When we do talk about taste in abstraction from a particular fruit, we rely on the vaguest of opposites, such as “sweet” and “sour.” When they talk about color in abstraction from an object, they rely on the vague opposites “white/light” and “black/dark.” We find nothing strange in using “sweet” for a wide range of different tastes, and we are happy to say “sweet a bit like a mango,” or “sweet like a banana,” or “sweet like a watermelon.” They find nothing strange in using “black” for a wide range of colors and are happy to say “black like a leaf” or “black like the sea beyond the reef area.”

In short, we have a refined vocabulary of color but a vague vocabulary of taste. We find the refinement of the former and vagueness of the latter equally natural, but this is only because of the cultural conventions we happen to have been born into. One day, others, who have been reared in different circumstances, may judge our vocabulary of taste to be just as unnatural and just as perplexingly deficient as the color system of Homer seems to us.

If it now feels a little easier to appreciate the power of culture over the concepts of language, then we can return to our story just in time to witness the outright triumph of culture in the early twentieth century. For it is an irony of history that while Rivers himself was unable to grasp the full force of culture, it was his work that was largely responsible for securing culture’s victory. In the end, what made the real impression was not Rivers’s agonized interpretation of the facts he was reporting but the force of the facts themselves. His expedition reports

were so honest and so meticulously thorough that others could look through his argumentation and reach exactly the opposite conclusion from the facts: that the islanders could see blue and all other colors just as clearly and vividly as we do and that their indistinct vocabulary of color had nothing to do with their vision. In the following years, some influential reviews of Rivers’s work appeared in America, where the vanguard of anthropological research was now forming. These reviews finally established a consensus about the universality of color vision among different races and, by implication, about the stability of color vision in the previous millennia.

This developing consensus was also corroborated by advances in physics and biology, which had exposed the critical flaws in Magnus’s scenario of recent refinements in color vision. The Lamarckian nature of Magnus’s model now emerged as just one of the gaping holes in his Emmental of a theory. Magnus’s physics of light, for example, turned out to be entirely upside down (or, rather, violet-side red). He had assumed that red light was the easiest color to perceive because it had the highest energy. But by 1900, it had become clear through the work of Wilhelm Wien and Max Planck that the long-wave red light actually has the

lowest

energy. Red is in fact the coolest light: a rod of iron glows red only because it is not yet

very

hot. Older and cooler stars glow red (red dwarves), whereas really hot stars glow blue (blue giants). It is actually the violet end of the spectrum that has high energy, and ultraviolet light has even higher energy, enough in fact to damage the skin, as we are constantly reminded nowadays. Magnus’s belief that the retina’s sensitivity to colors increased

continuously

along the spectrum also proved to be misguided, since, as explained in the appendix, our perception of color is based on only three distinct types of cells in the retina, called cones, and everything suggests that the development of these cones proceeded not continuously but in discrete leaps.

In short, by the first decades of the twentieth century it had become clear that the tall story about recent physiological changes in vision had been a red herring. The ancients could see colors just as well as we do, and the differences in color vocabulary reflect purely cultural developments, not biological ones. Just as one Great War was beginning in the

political arena, another great war seemed to have ended in the realm of ideas. And culture was the outright winner.

But culture’s triumph did not solve all mysteries. In particular, it left one riddle dangling: Geiger’s sequence. Or rather, it should have done.

til-la ša-du

11

-ba-ta ud-da an-ga-me-a.

The life of yesterday was repeated today.

(Sumerian proverb, early second millennium

BC

)

r ntt rf w

mw

d

ddwt,w

d

ddwt

d

d(w).

What is said is just repetition, what has been said has been said.

(“The Complaints of Khakheperre-seneb,”

Egyptian poem, early second millennium

BC

)

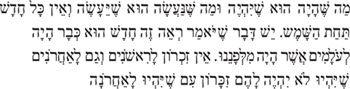

What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done; there is nothing new under the sun. Even if there is anything of which one might say, “See this, it is new,” it has already existed in ages that have gone before us. There is no memory of those in the past; of those in the future there will be no memory among those who will come afterwards.

(Ecclesiastes 1:9, ca. third century

BC

)

Nullum est iam dictum, quod non dictum sit prius.