Thoreau's Legacy (11 page)

Authors: Richard Hayes

Reverse Migration

Dale Elizabeth Walker

IN THE NATION’S HEARTLAND, WATCHING THE SEASONS shift their timing and the wildlife alter their migration patterns, I began to question whether I had made enough of a commitment to environmental stewardship. Photographs comparing a week’s supply of food for families around the world vividly demonstrate the massive size of the average American carbon footprint—not to mention our preference for suburban living, with stores, workplaces, and essential services just a drive away.

As a proponent of zero population growth, I brought only one child into this world. And with the example of a mother who crocheted plastic bread bags into functional doormats in the 1950s and ’60s, I worked hard to recycle before it was trendy. My cellar would fill with bottles and jars until the semiannual trip to a local bottling plant yielded a few pennies per pound for the glass I would deliver. I also spent a few years sorting recyclables at a collection center, while most surrounding communities were slowly adding recycling to their trash service.

But with unimaginably vast sections of the polar icecap splintering off and melting into the ocean, I knew I had to do more. Even before the price of gasoline topped four dollars a gallon, I began to realize that my idyllic home at the rural edge of suburbia was a luxury the earth could no longer afford. Though I have spent many pleasurable hours in the park across the road, holding my breath as great blue herons soared over the ponds and deer fed in the meadows, I resolved to move within walking distance of my job so I would no longer face a forty-four-mile commute each day. The housing market is shaky, and I’m not sure I will be able to sell my beautiful home anytime soon, but within the week I am closing on a loft less than a mile from my office.

I have never been an urban dweller, although it is in my blood—my mother and father both spent their earliest years in large eastern cities.

Now I look forward to

a life on foot

with a city to explore.

A library, museums, entertainment venues, restaurants, shops, a farmers’ market, and urban parks are just outside my new door. A large grocery will be opening six blocks away. Public transportation is also nearby.

It was the right time for me to reverse the historical American migration to wide-open spaces, to leave suburbia, with its miles of asphalt and traffic congestion, for the city lights. I will continue to recycle, although it will not be as convenient. My groceries will come home with me in cloth bags, and I will wear out a lot of shoe leather as I do one person’s part to shrink what has become an unsustainable impact on the earth.

Dale Elizabeth Walker

is a mom and grandmother who has worked for nearly twenty-five years in the field of law, primarily as a law clerk. She lives in Kansas City, Missouri.

Oracle

Russell Brutsche

I see the health of our biosphere as the ultimate social-justice issue.

I paint and create

music to evoke feelings and affect behavior in ways that words cannot. When I show my work in art galleries, most viewers agree with the messages I try to convey, but some do not. I may not be able to change their minds, but I hope that the images I’ve created will stay with them.

Russell Brutsche

is an artist and songwriter living in Santa Cruz, California. His paintings have been featured in numerous shows in the United States and Japan.

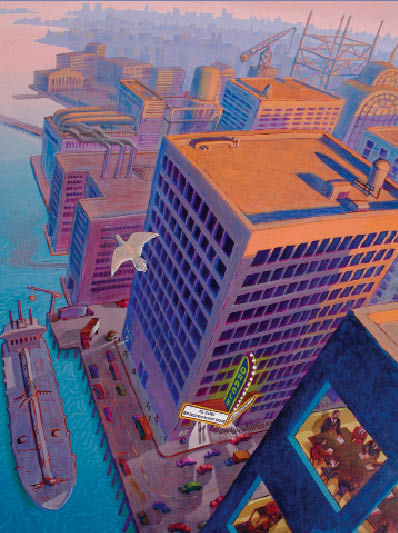

“Oracle,” acrylic on canvas by Russell Brutsche.

The Heat Is

Always On

Michael Gold

THE HEAT COMES UP THROUGH THE RADIATOR,

filling my New York City apartment with warmth it doesn’t need. It’s mid-November and 60 degrees. The pipes are banging as the hot air, fired by oil, comes up from the boiler in the basement.

The building managers think that

November is supposed to be cold

(and who could blame them?), so the heat comes up as scheduled. I open all the windows to bleed off the heat and welcome the cool breeze blowing in.

I hate the waste of it all. If the management could turn off the unneeded heat, we wouldn’t have to burn so much oil, which will only make us all warmer in coming years.

The place where I work operates on an even more unnatural heating schedule, sometimes starting in October. The room I work in feels like a blast furnace, and I open as many windows as I can to cool off. Doesn’t anyone realize that with our new warmer weather we don’t have to turn on the heat so early?

My daughter, who is two years old, runs to me for a hug whenever she hears the pipes banging in our apartment.

“Scared,” she says.

I ask her what’s scaring her.

“Heat.”

She thinks it’s a monster. I think she’s right.

Michael Gold

works and lives in Queens, New York. He and his wife, Frieda, have a two-year-old daughter, Miriam.

Apathy in the

Inner City

Sarah Flanders

AS A PSYCHIATRIST IN AN INNER-CITY CLINIC, I SEE

firsthand why some people remain apathetic about the destruction of the natural world. Modern urban life for poor and working-class Americans means limited education, constant media messages to buy manufactured goods, and few connections to the natural world. Outdoor recreation and city park facilities have declined along with health care, work opportunities, and social safety nets for disadvantaged city dwellers. It is hardly surprising that so many feel no reason to join the fight against global warming.

In the urban world, climate change is difficult to grasp

through direct experience.

At one time

Pittsburghers flocked to the city’s parks on summer days and nights, drawn to a racetrack, boating pavilions, an outdoor ball park, and even car-camping spots. But these attractions are gone, and the green spaces of our city often stand empty. Manufacturing has largely left Pittsburgh, so the dusty, gritty industrial neighborhoods are cleaner now, but for many residents the concrete infrastructure is the only world they know. They spend much of their leisure time indoors, watching television or playing electronic games. With vastly less time outdoors, many people cannot see how their world is affected by climate change.

Grappling with poverty, not to mention trying to avoid dying from inadequate health care, is a full-time job for many of the patients I see. If you can’t scrape together the bus fare to get to your doctor’s office, how can you feel energized by the immense challenge of stopping the destruction of the natural environment? Many of my patients have little security in their lives; they see no reason to quit smoking, let alone try to curb global warming. Poor people in this country aren’t ready to stop taking plastic bags from the store—why refuse what little you get that’s free?

Pittsburgh is surrounded by miles of open land and forest, and people here imagine that the earth will continue forever just as it is; no one has yet built a memorial to everything that has already been lost. If the movement to stop global warming is to succeed, it will have to educate all Americans, not just those who live in beautiful places, about nature and the history of environmental damage. To draw people back outside into the natural world, we need to make fundamental changes, starting with improved health care and living conditions for those who live in our cities. Only then will it be possible to dispel their apathy and ask them to join the effort.

Sarah Flanders

, a psychiatrist, practices in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where she lives with her family. She enjoys biking and gardening, and she volunteers as an urban ecosteward in Pittsburgh’s parks.

Above Portland

Gary Braasch

The tram, one of the latest elements in my hometown’s

innovative transport system,

allows medical personnel, patients, and students to avoid an estimated 2 million vehicle miles a year in traveling to the medical school. The tram carries more than 100,000 passengers a month along 3,300 feet of cables at about 20 mph. It connects with a trolley and light rail system that extends to many suburbs and the airport.

Gary Braasch

is an award-winning conservation photographer living in Portland, Oregon. He is the author and photographer of Earth Under Fire: How Global Warming Is Changing the World.

Above Portland. View from the top of the aerial tram at the Oregon Health and Science University. Photo by Gary Braasch.