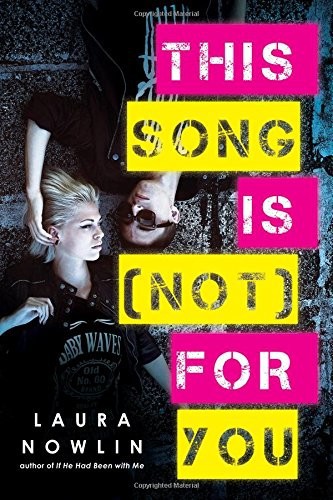

This Song Is (Not) for You

Read This Song Is (Not) for You Online

Authors: Laura Nowlin

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Love & Romance, #Social Issues, #Emotions & Feelings, #Dating & Sex

Copyright © 2016 by Laura Nowlin

Cover and internal design © 2016 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Nicole Komasinski/Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover image © Maja Topcagic/Trevillion Images

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Fire, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

This book is (totally) for

the Icebergs,

the kick-ass, avant-garde, in-your-face

experimental noise rock band

that let me hang out during practice

and call it “research for my novel.”

Robert Rosener,

Ausin Case,

and

Brad Schumacher, a.k.a. the Night Grinder.

Thanks, guys.

(But if you’ve read this book before

and you’re reading it again,

then this time,

the song is for you.)

Have you ever met someone and you could feel that they were going to be important to you? It’s like you never knew it, but you’ve been waiting your whole life to meet this person, and you recognize him with the same ease that you recognize your reflection.

That happened to me once.

• • •

When Sam told me his name, I laughed. It was like I should have already known. It was like he was already my Sam.

“Sorry,” I said. “I’m not laughing at you.”

“What are you laughing at?” he asked. We were standing on the stairwell outside the music department. Some guy knocked into his shoulder, but Sam didn’t react. When Sam is interested in something, it’s like the whole rest of the world has ceased to exist.

“It’s just, I feel like I should have already known that. You look like a Sam. Does that make sense?” I asked.

“No,” Sam said, and he gave me my first crooked smile. We were both freshmen, and it was the first day of school.

“I’m Ramona,” I said.

“That makes sense,” he said.

• • •

“I said that?” Sam asks. He frowns at his guitar. He’s replacing the B string, so I only have about one-eighth of his attention right now.

“Yeah, it was like we already knew each other’s names or something.” And then quieter, ’cause I’m not sure if I want him to hear or not, “Or felt each other’s names.”

Sam continues to frown at his guitar. I drum an impatient six-eighths beat on the garage floor. “Hurry up,” I say. “Nanami is waiting for us.”

Nanami is our band’s biggest and only fan. Whenever we post a new video on our web page, she comments immediately the next day. Someday when April and the Rain is super famous, we’re going to go to Japan on tour and meet her in person—and she will be thrilled.

Anyway.

I move my drumming off the floor and onto Sam’s sneaker. He doesn’t react.

“So, are we skipping band practice tomorrow?” I ask.

“Why would we?” He finally looks up at me, and when I see his eyes, I feel the familiar flutter in my chest. Sam has brown, sleepy eyes fringed with long, black lashes.

“’Cause we’re going to Artibus tomorrow! Did you forget?”

“No,” Sam says. “But I don’t see why we should skip practice. If anything, it should make us want to practice more.”

For years Sam and I have dreamed of escaping Saint Joseph’s Prep for the campus of Artibus College of Music and Arts. In case you don’t know, high school sucks. Our high school especially, because it’s full of rich kids—and the only thing worse than a poseur is a poseur with money. Sam and I don’t hang out much with anybody else.

We’re finally about to start our senior year. Summer is almost over, but first we have the admission evaluation tomorrow. School will start, and before we know it, we’ll be applying for admission over winter break. The end is in sight.

“Almost done,” he says.

I speed up my drumming on his foot.

“Ow! Okay, I’m done! Jeez, woman.”

“You know you love me,” I say.

“Yeah, yeah,” he says, but he gives me that crooked smile, and I know it’s true. I just wish it were a different sort of love.

• • •

It only took two days of being friends with Sam for us to start our band. In a month, he was the best friend I’d ever had. After a month and a half, I knew I was crushing on him hard, but I figured I’d get over it. I wasn’t going to put the band at risk just because I was having girlie feelings.

By the time April and the Rain was a year old, I had to admit that I was in love with Sam. We were sophomores, we’d put up our website, and we’d told our asinine classmates a hundred times that no, we weren’t dating.

Up in Sam’s room, we post this week’s video. Yesterday Sam came up with a killer riff, and today we played it in a bunch of different tempos, so I got to do some pretty cool tricks on my kit. Nanami is gonna love it.

“We need to keep practicing this one,” Sam says. “I wish we had just one more person to fill it out, maybe do a little vocal work.” Sam is always saying this, but I don’t think that lightning will strike us again. We were lucky enough to find each other.

Ramona was sleeping twenty-five minutes into the trip. I knew she would fall asleep. She always does when she has to be in a car for more than twenty minutes, and Artibus is an hour outside St. Louis.

Her mouth was hanging open, and she was frowning like she was dreaming of something that pisses her off, like dubstep.

She looked cute, but as a rule I try to ignore that. I turned up the radio.

“No,” she groaned.

“We’re almost there,” I said. “You’re gonna make a great impression at Artibus with dried-up drool on your face.” Ramona wiped her mouth with the back of her hand and sat up in her seat.

“How close are we?”

“We’re at the edge of town now. We have time to eat.”

“Cool. Let’s find a greasy diner that can be our place next year. We’ll go there so much that all the waitresses will know our names.”

I laughed. It was such a Ramona thing to say.

“Okay,” I said. “Let me know when you see this place.”

And before long, we did come by an appropriate-looking diner. The building was low to the ground and tucked back from the road. There was a semi in the parking lot and some half-wilted flowers in a pot by the door. The apostrophe and letter

S

on the neon sign had burned out.

“There!” Ramona pointed out the window. “Wanda Diner.”

“Wanda’s Diner.”

“That’s not what the sign says!”

I rolled my eyes and pulled into the parking lot.

• • •

It’s always like that with Ramona. She gets an idea, and then it happens. Like with April and the Rain. This one afternoon early freshman year, we were outside Saint Joe’s watching all the cars pull away, and she just announced, “We’re gonna start a band.”

“What?” I said. I was still baffled about why this pretty girl was hanging out with me. We only had one class together, but she always seemed to find me in the hallways, and that day in the lunchroom, she’d plopped down in the seat next to mine and started explaining riot grrrl’s influence on Nirvana. Later in the lunch hour, I’d learned that she was at Saint Joe’s as a faculty brat. Her dad taught Honors English and her mom was dead. But she said a lot less about both of them than she did about Kurt Cobain.

“A band,” Ramona said. “You and me. You’ll lead with whatever guitar you want. I’ll play the drums. I’m really good.”

“Maybe I’m not that good,” I said. “What about that?”

“You’re gonna be great,” she said. “We should get started tonight. I can come over, right?”

• • •

“Hello, Janet,” Ramona said to the waitress at our table. Janet glanced down at her name tag and looked at us skeptically over her notepad. “So, what’s good today?”

“Chili’s okay,” Janet said. “But it’s okay every day.”

“I’m Ramona,” Ramona said. “And this is my friend Sam. You’re going to be seeing a lot of us.”

“I think we need a minute,” I said.

Janet shrugged and walked away.

“Well, I think she’ll remember you,” I said. “As a lunatic.”

“It’s a start,” Ramona said. She smiled at me, and I had to look down at the menu.

Artibus looks okay. It’s trying a little too hard to be a picturesque private college. The grass and trees have that traumatized look of too much fertilizer and regular trimming, and the sidewalks are disturbingly white.

I arrived early and have been sitting in my car for twenty minutes now. It’s too humid to be outside for any length of time. I’m listening to Autechre, which helps.

Sara hated Autechre. “This song is creepy,” she would say. “This is Autechre, isn’t it?”

But now I’m remembering how much Sara hated Autechre, so I push the Skip button. Nils Petter Molvaer. Sara detested Molvaer.

Sara liked some good music, like Animal Collective. She also liked some really bad music, but most people do. And she liked that I was a musician. She was sweet and passionate about changing the world. That’s what I liked best about her.

But that still is what I like best about her. She’s not dead. She just broke up with me. She’s still out there liking her good and bad music and not understanding the difference, probably changing the song if something I gave her comes up on random.

Some guy on the sidewalk makes a weird face at my car. He doesn’t like Molvaer either. Or maybe it’s just my car. My car is part of a long-term art project that I call “Glitter in Odd Places,” or “GOP” for short. The objective is to influence society’s perception of glitter by introducing glitter enhancements to customarily nonsparkly items or situations. I used to take Sara out with me glitter bombing.

I pull the keys out of the ignition.

• • •

The music department is easy to find; it’s the biggest building on campus. It’s so hot outside that opening the front door feels like opening a refrigerator and stepping inside. There’s a sign right in front, “Admission Evaluations,” and a little arrow pointing to the left. Apparently, someone was worried that we would all get lost and wander around bothering the real students, because I don’t have to walk very far before coming to another sign pointing me in the direction I was already walking. A third sign leads me down a flight of stairs. “Basement,” the worried person has added in ballpoint pen.

There’s a small enclave with folding chairs. A woman who must be a parent is reading a book by the door. A guy and a girl my age are sitting in the corner whispering to each other. The guy has a guitar case, but the girl doesn’t have an instrument. She’s probably his enthusiastic and supportive girlfriend. I slump down in a chair far away from everyone else and close my eyes.

I open my eyes when I hear the door open. A girl comes out carrying a violin case and biting her lip. The woman stands and puts her arm around the girl. They whisper together as they walk up the stairs.

“Ramona Andrews?” A man with a clipboard is standing at the door now. The girl jumps up like she’s been waiting her whole life for this man to come for her. They disappear into the room together. The guy and I are alone now, but he’s bent over studying his shoelaces like they hold the secret to everything, so I doubt he’s going to be a bother. I lean my head back against the wall and close my eyes again.

• • •

The thing about Sara is that at first I didn’t think I would like her at all. She’s kinda cheerful, and usually I don’t like cheerful people because they aren’t really cheerful—they’re just fake. But Sara really was just like that.

Is

just like that.

We met, of all the stupid places people can meet, at a shopping center. I’d made the mistake of thinking that my sneakers were my own property to do with as I wished. I’d written the word “Darfur” over and over again on my left shoe and “Auschwitz” all over the right shoe. Then I’d designed and printed fifty copies of my own four-by-four informative pamphlet entitled “Darfur and Other Holocausts You Might Not Know About!” to hand out to anyone who asked about my shoes. It was my first PSA (public service art) and I was very enthused.

My mother had sworn with tears in her eyes that I needed to buy new shoes tomorrow (

tomorrow

) or she would lose her faith in all that was good. (Though further discussion had resulted in an agreement that I could wear my PSA shoes and go out in public in my own free time, but no, not at school.) That was on a Friday night. On Saturday morning (yeah, morning) I drove to the mall. And I promised myself that I would buy the first pair of shoes that I didn’t hate.

So I was staring at this wall of shoes, and this girl with a smile and a name tag came up to me.

“Can I help you?” she asked. And she was pretty (

is

pretty), but I’ve known a lot of pretty girls—or at least enough to be suspicious. I said that I kind of liked these one shoes but not really, and her face lit up. She said, “We have them in a darker color!”

And I could tell that she really was pleased. So I said okay, and she rushed off like she was on a mission. When she came back, I was surprised that I felt weird about taking my shoes off in front of her. I put the shoes on, and yeah, I didn’t hate them.

“Okay,” I said.

“Really?” She was so excited, and it really was sincere. She was like that even while ringing me up. I remember thinking that I’d never encountered somebody who could be that genuine with a stranger.

(I can be a bit prejudiced against people. I realized that about myself after being with Sara for a while.)

“By the way,” she said, “I like your old shoes. A lot of people don’t know about Darfur, or even what happened in Bosnia.”

• • •

I hear the door open. The girl comes into the hall. The shoelace-staring guy stands up. She grins at him and they high-five. The one professor dude from before says, “Samuel Peterson,” and then they high-five again. It is so fucking dorky that it has to be a real awesome moment for them. The guy and the professor walk into the room. When the door closes, the girl turns to me as if it is inevitable that we must speak.

“Hey,” she says. “I like what you did to your sneakers.”

“Thanks,” I say. “I have a pamphlet.”

She gets up and sits down a seat away from me. I hand the pamphlet to her and she studies it for a moment.

“I’m probably totally not adequately informed about global genocides,” she says. “I’m definitely going to read this.” Then she stretches her legs out in front of her and wiggles her toes inside her sandals. Her toenail polish is a chipped rainbow. “I’m auditioning for piano,” she says.

“I’m being evaluated for a general music major,” I hear myself saying. “They don’t have a program for what I really do.”

“Really? How are they going evaluate you? Are you nervous? What

do

you

do

? I play drums!”

This girl needs pixie ears.

I like her hair, which I’m pretty sure she cut herself. It sticks out of her head in tufts and bursts that no one could have planned.

“They’re gonna have me play some chords on the piano,” I tell her. “Sight-read some music. Have me do some vocals. Just prove that I’m generally competent with music, I guess.”