This New Noise (2 page)

Authors: Charlotte Higgins

The First World War hastened developments. As the early BBC employee Hilda Matheson wrote in her book

Broadcasting

(1933), ‘The Great War … gave an impetus to wireless communications, as to other forms of practical science, destructive as well as constructive. Directions could be sent by code, or

en clair

, to troops on land, to ships in distant oceans, to submarines, and to aeroplanes deploying over enemy territory.’ It was after the war that the advantages of sending one signal to a multitude of receivers were recognised. Many of those who had been working as wireless engineers for the military slipped into work for companies such as Marconi. But the appetite for broadcasting came from ‘the man in the street’, recalled Matheson: a community of wireless enthusiasts grew up, at first more excited by the notion that broadcasting could be done at all rather than by what was actually to be communicated. She wrote, ‘There was a host of men and boys with a passionate interest in mechanical contrivances – making amateur telephones from tin cans, rigging up improvised magnetic and electrical apparatus, in sheds, basements and attics, wherever they could find undisturbed corners in which to use lathes, batteries and tools in peace … from their ranks came much of the persistence and enthusiasm which provided the first public for broadcasting.’

In the meantime, wireless also became a topic of popular interest – an apparently miraculous phenomenon followed in the newspapers with wonderment. Manufacturers of wireless sets, such as Marconi, held licences granted by the Post Office to conduct experimental transmissions. On 15 June 1920 the

Daily Mail

arranged for a

recital by Dame Nellie Melba, who travelled down to the Marconi headquarters in Essex and sang for a half-hour, ending with ‘God Save the King’ via ‘Addio’ from

La Bohème

– her voice was heard clearly across Europe, and the event was widely reported. For the first time, broadcasting was planted in the British imagination as a medium replete with possibilities for entertainment. But, as these experiments continued, so disquiet in military circles grew. Wavelengths were being commandeered for ‘frivolous’, non-military use, it was felt. Briggs quoted a letter of complaint: ‘A few days ago the pilot of a Vickers Vimy machine … was crossing the Channel in a thick fog and was trying to obtain weather and landing reports from Lympne. All he could hear was a musical evening.’

A new settlement was needed. The wireless manufacturers’ experimental broadcasts were banned, and then, under pressure from the amateurs, allowed to continue under controlled conditions. The postmaster general, in response to a question in parliament about the future of broadcasting in April 1922, responded that ‘it would be impossible to have a large number of firms broadcasting. It would result only in a sort of chaos.’ Talks between the wireless manufacturers and the Post Office resulted in a scheme whereby the government would license wireless sets. A new British Broadcasting Company – with a monopoly on broadcasting – would finance its operations from a share of the licence fee and of royalties from sales of sets. Thus a funding mechanism for the service was devised, and the problem of the scarcity of wavelengths for civilian use solved. Moreover, the Post Office had followed a

pleasing path of least resistance – it had neatly avoided having to provide the service itself. To many, it seemed an eminently sensible arrangement. The

Manchester Guardian

’s leader of 20 October 1922 noted that ‘broadcasting is of all industries the one most clearly marked out for monopoly. It is a choice between monopoly and confusion … the only alternative to granting privileges and monopoly to private firms is that the State should do the work itself.’

By 1925, when the Crawford Parliamentary Committee on Broadcasting made its recommendations, some of the societal and political implications of the new service were beginning to become apparent. The decision was taken to transform the young British Broadcasting Company into a public corporation. Broadcasting was too significant to be turned over to mere profit-making. ‘No company or body constituted on trade lines for the profit, direct or indirect, of those composing it, can be regarded as adequate in view of the broader considerations now beginning to emerge,’ it reported. ‘We think a public corporation is the most appropriate organisation … its status and duties should correspond with those of a public service.’ Reith’s

Broadcast

Over Britain

had already laid out some of the abiding principles of the corporation-to-be. The BBC should be the citizen’s ‘guide, philosopher and friend’, he wrote. Broadcasting, in his hands, was moulded into something that was not merely a kind of pleasing technological curiosity, but a phenomenon with the capacity to ennoble those who used it. It may, he wrote, ‘help to show that mankind is a unity and that the mighty heritage, material, moral and spiritual, if meant for the good of any,

is meant for the good of all’. Wireless ‘ignores the puny and often artificial barriers which have estranged men from their fellows. It will soon take continents in its stride, outstripping the winds; the divisions of oceans, mountain ranges and deserts will be passed unheeded. It will cast a girdle round the earth with bands that are all the stronger because invisible.’

Reith was drawing on Shakespeare: it was Puck in

A

Midsummer Night’s Dream

who boasted that he could ‘put a girdle round the earth’. Reith cast himself as magician – more Prospero than Puck, for certain. I hear too the voice of his distant, adored preacher father in those rolling, ecclesiastical phrases. And Reith the younger was to outdo his father: his own congregation would consist not just of the good people of the West End of Glasgow, but the whole population of the United Kingdom, and all its empire.

Savoy Hill, London, the frost-hard January of 1929. The atmosphere in the offices of the BBC is, according to talks assistant Lionel Fielden, âone third boarding school, one third Chelsea party, one third crusade'. The head of variety, Eric Maschwitz, finds himself killing a rat in one of the dingy corridors one day by âthe simple method of flattening it with a volume of

Who's Who

'. There are studios, if you can call them that â âjust small rooms with distressing echoes', according to Fielden. His fellow talks assistant, Lance Sieveking, who has a âvivid and sometimes erratic imagination', has framed notices and set them beside each microphone: âIf you sneeze or rustle papers you will deafen thousands!!!' There is a creaking lift, a set of narrow stone stairs. Offices with coal fires. The BBC is partway through its triumphant march, at breakneck speed, from a staff of four in 1922 to a glorious future in the palatial Broadcasting House, where it will move in three years' time.

The BBC is a ânew and exciting dish, sizzling over the fire', according to Fielden. Val Gielgud is reinventing drama for the wireless. Percy Pitt is conducting music of all types, and Maschwitz is lending his debonair personality to variety shows. Reith stalks the corridors â âthis giant with piercing eyes under shaggy eyebrows', as Fielden thinks of him. Reith's chief enforcer and number two is

Vice-Admiral Charles Carpendale, who commanded the cruiser

Donegal

in the war â he tends to speak to Maschwitz as if he were âa delinquent rating'. The staff are a curious and heterogeneous lot â people âwho, often on account of some awkward versatility, or of some form of fastidiousness, idealism or general restlessness, never settled down to any humdrum profession after the war', according to Hilda Matheson, the BBC's first director of talks.

Miss Matheson's office: today, because of the cold, she is minded to hold her departmental meeting with everyone sitting âon the floor round my fire which shocks the great who may come in, terribly', she scribbles in a letter. Running the talks department, she presides over an extraordinarily mixed bag of subject-matter, and she must be master of it all â from theatre criticism to economics, from foreign affairs to tips for housewives. An ordinary morning's work sees her wrangling talks on crime and criminals, ante-natal care, readings of poems by Tagore, and discussions on market forces for farmers. âOh what a day, such a scramble â people, telephones, alarms and excursions, interviews, meetings,' she exclaims.

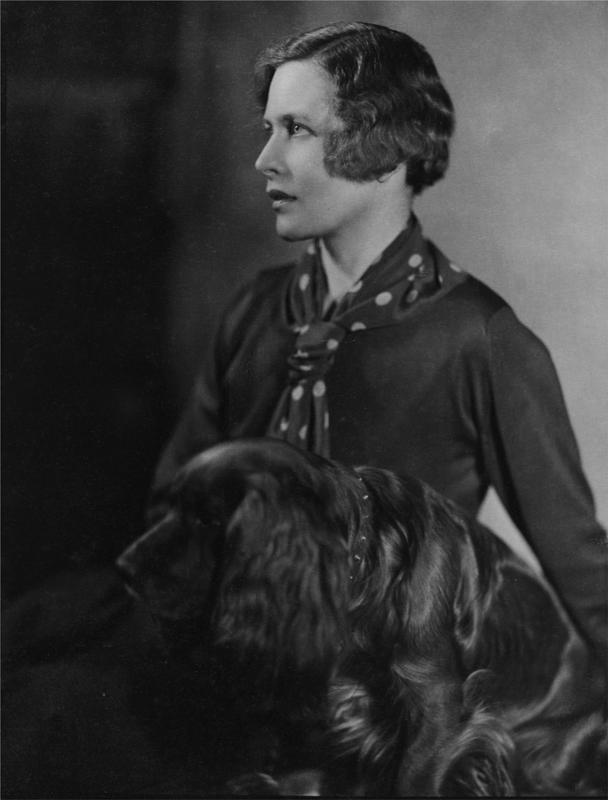

In January 1929 she is forty-one years old, with â

ashgold

hair and grey eyes', according to her old Oxford tutor, Lettice Fisher, the economic historian. She has neatly bobbed hair and a clear gaze. She is slender and fit â eleven hours' walking a day in Alpine Savoy is what she likes to do on holiday, and indeed what she will do for a fortnight come the summer. Sieveking and Fielden are her assistants, and the latter has had to come to terms with the

curious notion of a female boss. âI had at first thought that it would be strange, perhaps impossible, to work under a woman,' he remembered. But Matheson âdrew my admiration, respect, and affection almost instantly ⦠She was not supremely intelligent or supremely beautiful or supremely chic or supremely anything, she was just one of those people who are made of pure gold all the way through. You could not imagine Hilda panicking about anything, or failing to meet any situation with composure and charm.' Richard Lambert, editor of the

Listener

, remembered her as âearnest, intelligent, quick, sympathetic and idealistic'.

She might be calm as far as her juniors are concerned, but on 3 January she is feeling particularly overwhelmed by the claims on her attention:

The afternoon was so busy and my tray bulged so much that I began to get rattled and desperate and to think I couldn't cope with all the horrid accumulations â But Miss Barry took things in hand and calmed me down and saw me through â so all was well, but you know it's awful sometimes â the accumulations of anti-vaccinationists and Esperantists and propagandists on every subject and advertisement-mongers and Members of Parliament and pacifist organisations and women's organisations and Empire Marketing Boards and Channel Tunnel promoters and A. J. Cook and Lord Ronalds hay and Indian musicians and infant welfarers ⦠a little overwhelming in the mass.

Hilda Matheson: âearnest, intelligent, quick, sympathetic and idealistic'

The following day, perhaps thanks to Miss Barry's secretarial efforts, things are more fun, but still wildly busy: â⦠an interview with and voice test of an Afghan, an intelligent fellow and wise I thought â followed by a similar process with a charming docker called Bill â a great find

â followed by an hour's discussion with Lionel and a man I have found in the music dept who knows as much about poetry as about music â¦'

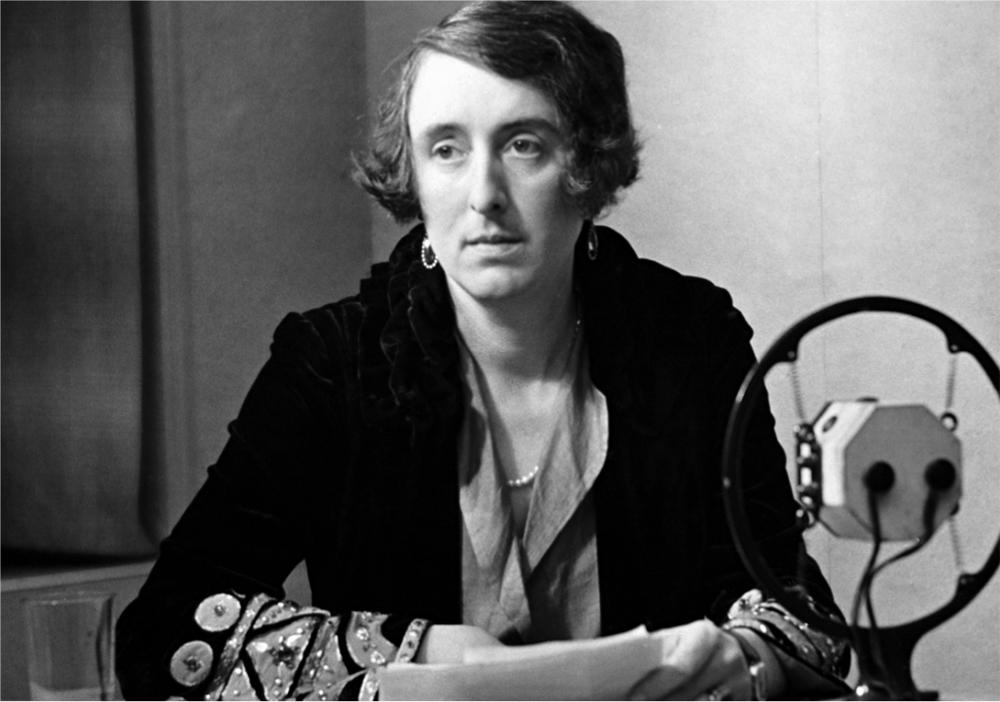

In truth, Matheson is struggling to concentrate. Because she is in love â drowning deliciously in it, drugged and drunk with it, utterly brimming with it. She has been in this intoxicated state ever since Monday, 11 December 1928, when Vita Sackville-West, whom she first met the previous summer, came in to the BBC to give a broadcast talk on âThe Modern Woman'. Sackville-West once described the sheer oddness of the new skill of broadcasting in a letter to her husband, Harold Nicolson: âYou are taken into a studio, which is a large and luxuriously appointed room, and there is a desk, heavily padded, and over it hangs a little white box ⦠There are lots of menacing notices about “

DON'T COUGH

â you will deafen millions of people”, “

DON'T RUSTLE YOUR PAPERS

” ⦠One has never talked to so few people, or so many; it's very queer.' After the âModern Woman' talk, Sackville-West and Matheson spent the night together, and on the Tuesday Matheson stayed off work. On the Wednesday, she wrote to Sackville-West, âAll day â ever since that blessed and ever to be remembered indisposition â I have been thinking of you â bursting with you â and wanting you â oh my god wanting you.'

More than a hundred letters from Matheson to Sackville-West survive, mostly from late December 1928 and the first months of 1929, when Sackville-West was in Berlin with Nicolson, who was serving at the British embassy. Sackville-West's letters are lost â perhaps destroyed

by Matheson's family after her death. In her correspondence, Matheson imparts a flesh-and-soul impression of the triumphs and frustrations of work within the young BBC. It is an account â knitted tightly into her outpourings of passion and desire â that dovetails intriguingly with the trail she left in official memoranda and letters to contributors, as well as in her own published writing. (She wrote an illuminating work,

Broadcasting

, for the Home University Library; and was for a time in the 1930s the

Observer

's wireless critic.) One letter to Sackville-West is written on an official âinternal circulating memo' template, with its bossy instructions for use: âWrite minutes

BELOW

each other and not at all angles â Number your minutes â Don't write minutes in the margins â' It is headed âTo: Orlando. From: Talks director. Subject: Us.' Matheson was referencing Virginia Woolf's novel

Orlando

, which had been published the previous October, and whose gender-shifting heroâheroine was based on Sackville-West. âI shall write to you on a different office form every day,' she wrote in her speedy, fluidly efficient hand, âpartly to show you the world in which I work, partly to assure myself that it really is me â a filler-in of forms, a writer of memoranda â that you love. Besides I see I shall have to write to you at all sorts of odd moments during the day â covertly in Committees â and this looks so official, nobody would guess.'

Vita Sackville-West: âOne has never talked to so few people, or so many.'

That January, Matheson had a momentous project to undertake: organising the first ever broadcast debate between politicians from the three main parties. A ban on âcontroversy' in broadcasting had been lifted in 1928, but the BBC was still treading carefully. Endless negotiations were necessary to bring speakers from the Conservative, Liberal and Labour parties together round the microphone to discuss the forthcoming De-rating Bill. (This was legislation, designed to boost the depressed economy, that freed industrial and agricultural premises from local-authority taxation.) On 3 January she wrote of her day, âBack rather late to find a frenzied Admiral Carpendale sending himself into fits over politics â so I had to draft an ultimatum to the parties for him â rather fun that was.' Later in the day â her letters could stretch over numerous pages, added to at intervals â she becomes the ardent lover again: âI know that I want you â it engulfs me like a huge wave and I just have to wait till it's passed over my head before I can breathe again ⦠sometimes I want you so terribly

physically that I can hardly bear it.' Then she switches back to the question of the political debate, telling of a subsequent phone call from Carpendale: âHe's got cold feet because he thought I had rushed him into unseemly and inaccurate letters to the three political parties and I couldn't quite be convincing. Darling, he was so accusing and unfair that I got all hot and bothered â¦'

The following week, on 10 January, the arrangements were still being fought over: âOne final effort to secure my politicians â for the hundredth time of asking â thank heaven they're all fixed now â for the first big political discussion we've yet had ⦠they're all as nervous as cats.' The listings deadline for the

Radio Times

had been missed (it is partly for this reason that the politicians who actually spoke are lost to history, though the government spokesman is likely to have been Neville Chamberlain, then health minister, who was behind the bill). The debate, in the end, was âa great success'. The politicians were âso very sweet in their passionate desire to be strictly honourable about their allotted time'. Not an impulse, perhaps, that survived long into the broadcast age. The format, too, would surprise current audiences for broadcast political debates. Each speaker was allowed to speak for 20 minutes, with the government spokesman allotted a further 10 minutes at the end. âIt honestly wasn't dull,' promised Matheson. Listeners' letters, she wrote a few days later, were âpouring in' and they were âquite amazing'. There was âa common admission that they hadn't been interested in these things before, but the discussion made them want to know more'.

Matheson, who was born on 7 June 1888, was, like Reith, a child of the manse: her father was a Presbyterian minister in Putney, south London. When she was a teenager he suffered a nervous breakdown, and the family had a spell in Switzerland while he recovered. Matheson was also sent to spend time with families in Stuttgart and Florence. On their return, her father became the first Presbyterian chaplain to students at Oxford, and she studied history as a home student â this in the days before women were officially recognised as members of the university. It was perhaps in Oxford that Matheson made the contacts that led to her recruitment into secret work during the First World War. She was posted to Rome where âshe had the task of forming a proper office on the model of MI5 in London', remembered her mother. Italian officials turned up simply to marvel at her â they were âvery incredulous about the capacity of a young girl, for she did look absurdly young then, to do such work'. (She was twenty-six on the outbreak of war in July 1914.)

After the war, she became political secretary to Nancy Astor, the first woman, in 1919, to take up a seat in the Commons. Astor remembered: âThose first years in Parliament were only made possible by her unremitting work and service, not for me, but for the cause of women ⦠I might describe it as my zeal and her brain.' As part of her work for Astor, Matheson organised a series of receptions where MPs might meet significant women, âin whom', remembered her mother, âthey had got suddenly interested because they had just got the vote. It was to one of these gatherings she invited Sir John Reith, and he was clever

enough to realise that if he could get Hilda, who knew everybody, to come to the BBC he would be doing it a good turn.'