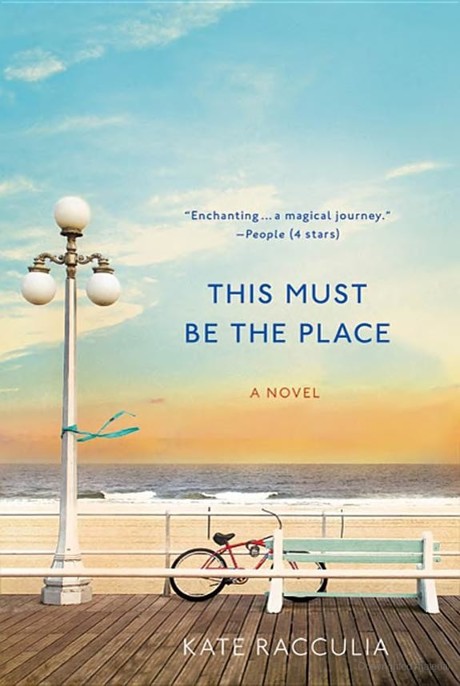

This Must Be the Place: A Novel

Read This Must Be the Place: A Novel Online

Authors: Kate Racculia

Tags: #Fiction, #Contemporary Women

This Must Be

the Place

the Place

Kate Racculia

Henry Holt and Company

New York

Henry Holt and Company, LLC

Publishers since 1866

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

www.henryholt.com

Henry Holt

®

and ®

®

are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Copyright © 2010 by Kate Racculia

All rights reserved.

Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Racculia, Kate.

This must be the place : a novel/Kate Racculia.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-8050-9230-1

1. Boardinghouses—Fiction. 2. New York (State)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3618.A328T48 2010

813'.6—dc22 | 2010001434 |

Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums.

For details contact: Director, Special Markets.

First Edition 2010

Designed by Meryl Sussman Levavi

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

For Mom and Dad

11. Real Boys and Girl Friends

13. Missing Persons on Vacation

This Must Be

the Place

Amy considered the postcard: a boardwalk scene. Throngs of people wandering in the sun. Sparkling blue ocean to the right, cheery awnings on the shops. She sniffed. The man beside her on the bus stank of tuna fish and cigarette smoke.

This must be what it feels like to die

, she thought.

She was sore all over, sore and too tired to be scared. She suspected this

was

what it would feel like to die: to give up everything that came before, to just—cut it off. Tear it out. She wasn’t religious. Her parents died before they had a chance to impart much wisdom on the nature of immortal souls, and her grandfather, when she first went to live with him, told her he was allergic to church. But she suspected there was something beyond what she knew. Beyond what she could touch and smell. She suspected there was a sort of transition period, where you had a chance to say good-bye to your old self and your old life, and this was hers, on this Greyhound, her sandaled feet propped on her backpack, with nothing but a postcard on which to mark her passing.

Not that she ever intended to mail it.

She’d never intended to, not even when she bought it. She’d been waiting for Mona to finish her shift at the pizza place—and by

finish her shift

Amy meant

break the suction with her boyfriend’s face

—and was killing time in one of those boardwalk junk shops. The boardwalk was full of junk; there was shit

everywhere

. Key chains and T-shirts and snow globes (how lame was that, snow globes at the beach?), and stupid little sculptures built out of shells; Amy, of all people, could appreciate tiny objects, but there was just so

much

. It made her think of how many people there really are in the world, and whenever she thought about

that, she felt suffocated and insanely lonely, which was classic irony when you thought about it: that realizing she was one of a million billion or whatever made Amy Henderson feel like she would never be anything but alone.

She bought the postcard because the guy behind the counter was giving her weird looks and she wanted to prove to him that she wasn’t loitering, even though she was: she was a fucking grown-up. She had money.

She smoothed the card over the top of her leg:

OCEAN CITY MISSES YOU!

said bright red letters across the sky. Hardly. She chewed her pen and turned the card over to the blank side and wrote,

Mona, I’m sorry

.

She didn’t know what else to say, so she filled out the address. She still wasn’t going to send it, but it felt good to state the facts:

Desdemona Jones, Darby-Jones House, Ruby Falls, New York.

Maybe she should apologize a little more.

I should have told you

, she wrote.

What was the one thing she wanted to tell Mona? What could you put on a postcard—knowing that some nosy postal worker would probably read it, and you barely had enough room to say anything important anyway?

You knew me better than anyone—I think you knew me better than me.

That would make Mona happy. Mona wanted to be someone’s best friend more than anything in the world. It was a little pathetic; but then sometimes it made Amy a lot happier than she wanted to admit.

Mona would worry, so next she wrote:

Don’t worry. I swear I’m happier dead

, which was a little mean, because it would make Mona wonder whether Amy had flung herself off a cliff or across some train tracks or taken a whole bunch of pills and gone to sleep. But Mona should know better. If Amy hadn’t done any of those things while they were still stuck in Ruby Falls, she sure as

hell

wasn’t going to do it once she finally escaped.

It was getting late, and Amy wasn’t so tired that she didn’t know how hungry she was. She’d bought a few bags of pretzels at the last bus station, and now she crunched into them happily, her lips shriveling from the salt. She started to remember where she was going, and that of

course made her remember where she’d just come from, and she thought of Mona, who would have been so scared when she found her just—

gone

.

She didn’t know why she’d done it. She woke up early and knew today was the day (or rather, yesterday was the day; she’d been on this bus for something like twenty hours now), and when you knew something, there was no point in not-knowing it, just like there was no point in waiting. What day was it, the eighteenth? She uncapped her pen and wrote

August 18, 1993

on the top edge of the postcard, where the stamp would go. Her stomach and her knees and her butt hurt, and she was grateful to be in the window seat, even though it was dark and there wasn’t much to see. She pressed her forehead against the cool glass.

She thought she was in Indiana, or Kansas maybe, by now. Hollywood was closer than ever. Her future was closer. The world flickered by, unspooling like a reel of undeveloped film.

The darkness of the bus, close and warm, reminded her of sitting in the dark of a movie theater on the boardwalk with her father, a million years ago, it seemed: the summer before he died, when she was four and he took her to see

The Clash of the Titans

on a rainy day when it was too cold to go to the beach. “This is Ray Harryhausen’s masterpiece,” he whispered to her. “You think those skeletons in

Jason and the Argonauts

are cool, wait till you see Pegasus. Wait till you see Medusa. Wait till you see the Kraken.” She remembered sucking the chocolate coating off each Junior Mint and thinking it was funny that there was sand on the floor, like the beach just couldn’t stay away, and then the lights came down and she forgot about the mints and the sand. She left the earth completely. She traveled to Olympus. She rode the back of a white winged horse. She shrank from the red death rattle of Medusa and goggled at the great titan of the sea, the Kraken, as it rose screaming from the depths to claim the sacrificial Andromeda.

And he—Ray Harryhausen—had created them! Had

built

them, improbably, from wire and clay and plastic and feathers; built them and given them movement, and desire, and souls. Harryhausen, come to think of it, was the only god she had ever learned to worship; he created a world in his movies that captured her, that thrilled her, that felt like home. It was a world she’d spent her entire life trying to find.