This Is Your Brain on Sex (5 page)

Read This Is Your Brain on Sex Online

Authors: Kayt Sukel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Human Sexuality, #Neuropsychology, #Science, #General, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Life Sciences

A Separate System for Romantic Love

Fisher, Brown, and Aron used a similar photo viewing task in their fMRI study. Instead of asking participants just to think of their beloved, however, they also asked participants to think about specific events relating to the person, such as a romantic dinner or a recent trip to the beach—any situation in which they were together, excluding those of a naughty nature. Despite this slight change in focus, their results showed quite a bit of overlap with the Bartels and Zeki study. Fisher took these findings and suggested

a coherent theory of love: three distinct yet intersecting brain systems that correspond to sex, romantic love, and long-term attachment (like a mother-child bond or the comfortable relationship you might see in a couple who have been married for sixty years). These three separate systems, she argued, could cover all facets of love: romantic, parental, filial, platonic, and that old bugger, lust.

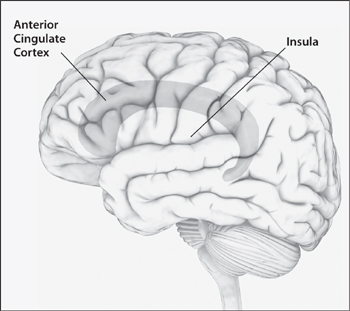

Areas activated in the original neuroimaging study of love by Semir Zeki and Andreas Bartels. This study also found a significant decrease in prefrontal cortex activation.

Illustrations by Dorling Kindersley.

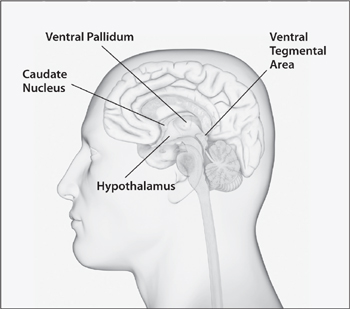

Helen Fisher and her colleagues hypothesize that there are three distinct systems involved in love: the hypothalamus for lust, the caudate nucleus and ventral tegmental area for romantic love, and the ventral pallidum for attachment.

Illustration by Dorling Kindersley.

Scientists have long known that the

seat of the sex drive is the hypothalamus. When it is removed, folks lose all interest in sex, as well as the ability to perform sexually. This almond-size brain area is linked to the pituitary gland, which produces the hormones necessary to fuel the desire to “get it on.” Humans are more than just their sex drives, however. With romantic love, Fisher and her colleagues observed brain activity in areas outside the hypothalamus, including the right ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the right caudate nucleus. These are both part of the basal ganglia, a brain area connected to both the cerebral cortex and the brain stem. The basal ganglia, along with the hypothalamus and amygdala, is implicated in reward processing and learning. It’s a little like bribery: when we experience something that feels good, such as satiating our hunger, having a sexy romp, or spending time with the object of our affections, these areas of the brain give us a little extra boost to encourage us to do it again. If we are talking about deep emotional attachment, the ventral pallidum, a different

part of the basal ganglia circuitry, is activated. All these areas are very sensitive to the neurochemicals dopamine, oxytocin, and vasopressin, which are thought to be pleasure-inducing and critical to forming pair-bonds in socially monogamous animals (to be discussed in more detail in chapter 3). But they each work a little differently.

6

The two regions that seemed most important to romantic love in the Fisher study were the caudate nucleus and the VTA. These areas reside in what is called the “reptilian brain”—a cluster of subcortical regions near the brain stem that have existed since before we evolved to walk upright—and are strongly implicated in both reward processing and euphoric feelings. They are also part of an important dopamine-fueled circuit called the mesocortical limbic system, a pathway critical to motivational systems; unsurprisingly it’s a circuit that has been implicated in addiction. These study results led Fisher, Aron, and Brown to conclude that romantic love is not an emotion, but a drive. According to Brown, “Love is there to help fuel reproduction, to help us psychologically by connecting with others. It is distinct, yet related to lust and attachment.”

Think of it this way: Lust may be the simplest of the three hypothesized systems, an almost reflex-like process that keeps us getting busy. Certainly if it were a more involved process, we would not find ourselves so interested in individuals like Pamela Anderson in all her

Baywatch

glory or, like one of my girlfriends who is too embarrassed to be named, totally hot for the

Jersey Shore

’s resident Lothario, Mike “The Situation” Sorrentino, right? At the same time we also have a system for attachment. Feeling connected to someone is a rewarding behavior, hence that ventral pallidum activation; it is nice to have someone to come home to, even if you are no longer inclined to jump his or her bones 24/7. Somewhere in the middle is the romantic love system, connected to both lust and attachment. It hits on areas involved in attachment and lust, as well as those implicated in reward processing and learning. It is no surprise that romantic love feels good and helps us to bond with another person (and consequently promotes procreation).

“These brain systems often work together, but I think it’s fair to say they often don’t work together too,” Fisher told me when I asked whether these three systems overlapped in other ways. “One might feel deep attachment for one partner, be

in romantic love with another partner, and then be sexually attracted to many others. There’s overlap, but like a kaleidoscope, the patterns are different.” It is also possible that these systems work on a bit of a continuum: one’s physical attraction for a person can develop over time into romantic love and then into a deep-seated attachment. It might even work the other way: a good friend to whom you are deeply attached may one day, inexplicably, seem physically irresistible. A quick flick of the wrist, a change in circumstance or age, and the kaleidoscope may offer you a completely different configuration.

Love Also Deactivates

At times active brain areas are not the only ones that are important to understanding function; deactivated areas can tell us something too. These neuroimaging studies have also shown decreased activation, which may be related to decreased function, in certain brain areas. The frontal lobe, the parietal lobe, and the amygdala show diminished blood flow in love and attachment. They say love is blind, and if you’ve ever been in love with the wrong person, you know it to be true. Zeki argues that the lack of blood flow to these areas suggests reduced function in judgment, decision making, and the assessment of social situations.

You Were Always on My Mind

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but you do not need explicit visual stimuli to activate the brain’s romantic love system. Stephanie Ortigue, a neuroscientist at Syracuse University, noticed that people in love are very quick to make associations between the object of their affection and certain words and concepts. If a place, word, situation, or song has the slightest thing to do with their sweetheart, they will make all kinds of interesting connections. People in love cannot stop thinking or talking about their boo. This priming effect, the strength of connections between your beloved and everything related to him or her, may facilitate that kind of quick recall. Ortigue decided to take a look.

Ortigue and her colleagues scanned the brains of thirty-six women who were passionately in love while they were subliminally presented with the name of their significant other.

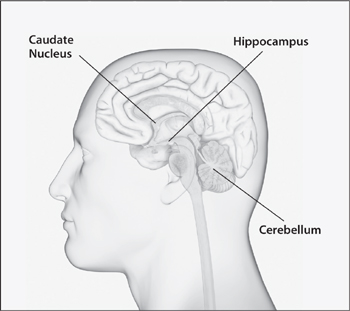

It would seem that, even implicitly, love really has a strong hold on the passionately in love individual. Even when words were used instead of photos, many of the same subcortical reward-related brain areas fired up in this study, as in previous neuroimaging studies: the caudate nucleus, insula, and VTA. But these researchers also documented activation in higher-order brain areas, parts of the cortex involved in attention, social cognition, and self-representation: the angular gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, and superior temporal gyrus.

7

Stephanie Ortigue’s study using names instead of photos found activations similar to those in the Zeki and Fisher studies. She also found higher-level activation in the angular gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, and middle frontal gyrus.

Illustration by Dorling Kindersley.

“Our findings suggest not only that these reward systems are important in love but also more cognitive areas related to decision-making and the representation of self and body image,” said Ortigue. “It’s quite interesting—it suggests that love may be an extension of oneself. Or rather, people in love really put themselves into others. It changes the way we conceptualize passionate love.” If my love object can change the way I internally view myself, what else might change? This research brings a whole new meaning to the line “As your lover sees you, so you are.”

Putting the Pieces Together

Though Fisher postulates that romantic

love is a drive—one that has been evolutionarily selected in order to motivate us to have babies and raise them as pair-bonded couples—Ortigue cautions that it is dangerous to simply classify love as a basic instinct. There are too many different brain areas implicated.

She has a point. No part of the brain area is an island; all of these regions are interconnected and send signals to and from one another. What’s more, one area is not limited to a single function. One of my neuroscience professors once joked that the brain is the “ultimate recycler” because it has evolved over the past hundred million years to be superefficient. After all, it takes a lot of blood and energy to run a brain. It would be a serious waste of resources if single regions couldn’t help facilitate a variety of tasks. The brain frowns on redundancies—and with good reason.

In an analysis of all neuroimaging studies done on love (a whopping six in the past ten years), Ortigue identified twelve distinct regions that were activated across different types of tasks, such as viewing photos or watching videos of a loved one or being subliminally presented with a lover’s name.

8

Given current limitations in neuroimaging technology, including measurement timing, which may not be able to keep up with the lightning speed of neural signaling, it is unclear which of these areas lights up first in romantic love, let alone how and when the different areas may interact. Nor is it apparent how our subcortical brain regions, the so-called reptilian brain implicated in reward processing and euphoria, may be influencing the higher-level cognitive areas involved in attention, self-representation, and decision making and vice versa. There is still quite a bit to learn.