This Is Your Brain on Sex (4 page)

Read This Is Your Brain on Sex Online

Authors: Kayt Sukel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Human Sexuality, #Neuropsychology, #Science, #General, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Life Sciences

Claudius Galen of Pergamum, a second-century Greek physician and philosopher, was one of the first to give more credit to the brain based on actual biological observations. This was likely due to his job: before he became the most influential physician of his time, he worked as a surgeon to the gladiators, where he surely witnessed ample evidence of what a good blow to the head could do to personality, movement, and behavior. In his treatise

De usa partium corporis humani (On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body),

he argued that the

encephalon

(that’s Ancient Greek for brain) must be responsible for both movement and perception. Otherwise it would not be attached to the sources of the senses (eyes, ears, nose, and mouth) as well as to the major motor nerves. He did not think the brain had anything to do with intelligence, per se—after all, plenty of stupid animals had fairly developed brains—but it was the organ that helped us process sensory input and respond to it with the appropriate bodily movements. Even with this focus on the brain, Galen still had room in his theories for the heart. He believed it was the seat of our “vital spirit,” a vapor that traveled through the veins and arteries and powered the “animal spirit” in our brains.

2

Localizing Function in the Brain

Over the next several centuries theories on what the brain does and how it does it proliferated. Through the careful study of patients with brain damage, scientists eventually came around to the idea that mental functions originate in the brain. It took a while, though; the idea did not really catch on until the nineteenth century. By then most scientists conceded that different areas of the brain were responsible for specific and localized functions. The next logical step was to determine which bit of brain was responsible for what.

One of the first to take a stab at making

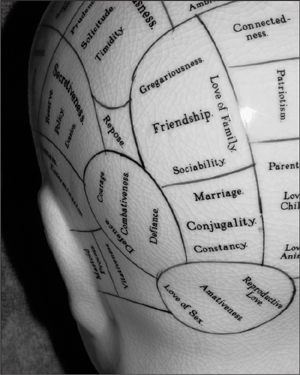

a functional map of the brain was Franz Joseph Gall, a German physician and anatomist who examined both the cream and the dregs of society in order to understand brain organization. By looking carefully at the skulls of poets, politicians, mothers, murderers, thieves, philosophers, prostitutes, and scientists (and probably anyone else willing to sit for him), he and Johann Gaspar Spurzheim created the theory of phrenology—often referred to by the slang term “bumpology.” It may sound more like the name of a quirky hip-hop song than a respectable theory of science, but it was all the rage in the mid-1850s.

The theory was fairly simple. Gall postulated that the brain had distinct parts, regions that he referred to as “organs,” where qualities like wit, memory, courage, destructiveness, mirthfulness, and even metaphysical ability were localized. The bigger the organ (the size of which directly correlated with one’s propensity for the associated quality), the more it would protrude, pushing out the skull. If you lacked a certain faculty, there might even be a small hollow in the cranium to show this. According to the theory, a good student should have buggy, protuberant eyes to make room for the larger memory and language organs behind them. A violent criminal would have a series of distinctive bulges directly behind the ears. And a venerable man should show some size right on the top of the crown—perhaps on which to better rest a halo.

In a practical manual of phrenology originally published in 1885, the president of the American Institute of Phrenology, Nelson Sizer, and his colleague H. S. Drayton wrote, “Phrenology teaches that every sentiment, every element of taste and aversion, of hope and fear, of love and hatred, as well as the intellectual faculties and memory, have their special seats in some part of the brain.”

3

By simply running a deft hand over the topography of the cranium, you could learn all you would ever need to know about a person.

This theory included love. Place the palms of your hands over your ears. Reach back with your fingertips and feel the back of your head. In Gall’s day this part of the skull, the occiput, was considered the location of a person’s “domestic propensities,” that is, the distinctive brain organs responsible for amativeness

(physical love), conjugal love, parental love, friendship, and inhabitiveness (a love of home). Phrenologists believed a well-rounded person should possess a smooth, elongated, and broad occiput—a balanced grouping of these various love-related organs. Sizer and Drayton explain:

The back of a phrenology model, highlighting the areas thought to be responsible for “domestic propensities” such as amativeness, conjugality, and friendship.

Photo by the author.

[Individuals] may be intellectually wise; they may be technically honest as to property and social rights, but if they lack Parental Love they will not want children; if they lack Conjugal Love they will not want marriage. If they have strong Amativeness, they may desire society through action of that faculty. . . . Free love animals and free love men lack something which does them no credit. Conjugal Love, the special, life-long, individual and exclusive mating, is human, honorable, natural, and the only sound philosophy of sexual mating.

Basically, if you were looking for love in the Victorian age, you had better hope to have your chaperone distracted long enough for you to get a good feel of a potential mate’s occiput before committing to anything permanent. According

to phrenologists, one misplaced lump or chasm could make all the difference to your future happiness.

No matter that the spot that Gall and Spurzheim denoted as the seat of that dratted amativeness is not even adjacent to the brain. It lies next to some sinuses and veins, a good distance away from any gray matter. This little inaccuracy illustrates one of the many problems with phrenology. While Gall and Spurzheim’s basic idea that bits of brain underlie different functions fits right in with today’s neuroscientific theories, their focus on both expansive, ill-defined traits (just what might an organ for “firmness” or “sublimity” refer to?) and the exterior as opposed to the interior of the skull means it is not a scientifically sound theory.

Although phrenology eventually crashed and burned in both the popular and scientific dominions, the concept of function localization managed to stick around. For the next two centuries scientists focused on trying to pinpoint areas of the brain associated with memory, language, attention, and movement by observing patients with brain damage and animal models as well as using a variety of electrophysiological techniques. Even these “simple” concepts were difficult to study in the brain. Something like love, with its associated erotic, cognitive, and goal-directed behaviors, was too much for many researchers to even consider studying, especially since it was unclear what

love

might be. Was it an emotion, like sadness or fear? A drive, like hunger or thirst? A human construct to justify sex that had no basis in biology whatsoever? No one knew for sure. The fact that scientists could not pin it down made love seem impervious to serious scientific inquiry—and put it on the research back burner for more than a century.

Scanning Love

In the late twentieth century advances in technology enabled researchers to transcend one of phrenology’s biggest failings. Neuroimaging techniques like computerized axial tomography (CAT) scanning, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and positron emission tomography (PET) allowed scientists to look inside the skull and observe the living, working brain instead of relying on cranial bumps, autopsy specimens, or

animals. These new approaches provided more detailed analysis of localized brain function. But it was not until the early 1990s, when a new technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) hit the scene, that neuroscientists could look deeper and attempt to localize something as shambolic as love.

How does fMRI work? It is all about the blood flow. Like all organs in the body, the brain needs blood in order to work. Even the smallest area of neural activity is accompanied by an influx of oxygenated blood. The brain uses that oxygen to facilitate function and then sends it on its way. This point is key for measuring activation using the fMRI. Oxygenated blood has different magnetic properties from deoxygenated blood. A large spinning magnet in the fMRI can track where the blood goes and how that blood flow changes over time. By following that track, neuroscientists can see what areas of the brain are active in response to different stimuli and tasks.

Who first thought to try to map the neural correlates of love is up for debate. In the late 1990s both Andreas Bartels, a newly minted PhD at University College London, and Helen Fisher, that savvy evolutionary anthropologist from Rutgers University, believed there must be some neurobiological evidence of love in the brain. It just had to be tested. But since the days of phrenology, no one had really tried.

Fisher had been studying the anthropological aspects of human sexuality, monogamy, and love for decades. Her research convinced her that romantic love was not an emotion, as so many others had postulated, but an actual physical drive like thirst or hunger. “It just came to my mind that romantic love was a very powerful

physical

experience,” she said when we discussed her first study about the brain and love. “And that if I looked at brain functions, I might be able to establish what was going on in the brain when someone falls in love.”

After speaking about this idea at several conferences, Fisher linked up with Lucy Brown, a neuroanatomist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine; and Arthur Aron, a social neuroscientist from the State University of New York at Stony Brook. The group hypothesized that there were three distinct brain systems for love: one for sexuality and sexual behavior, a second for feelings of deep attachment, and a third for romantic love.

4

“It seemed to me that there were three basic feelings that go with love, and all others sort of derive

from them,” said Fisher, her voice thoughtful and calm. “I thought romantic love would be the easiest one to measure. It’s such a dramatic feeling, with strong elements of focus, energy, and motivation.”

Fisher is right; love’s symptoms are both physical and dramatic. Those afflicted by it are often distracted, constantly daydreaming about their intended. They are emotional, too, prone to exaggerated laughter, tears, and fears. One cannot forget the actual physical manifestations of this condition: new lovers may feel butterflies in the stomach and experience an elevated heart rate, sweaty palms, and weakness in the knees. These individuals may exhibit signs of anxiety, loss of appetite, and slight obsessive-compulsive tendencies, as well as poor decision-making ability. They may sneak out of the house at night, be consistently late for work, drop out of college, or move to a new city for no other reason than to be with their lover. In my case, I blame my irrational purchase of an obnoxiously purple couch solely on the fact that I was head over heels with the object of my affection while shopping for it. Fisher was strongly convinced there was a biological explanation underlying these extreme changes in behavior. She and her colleagues set out to find it.

But before the group completed their testing, Bartels and his former advisor, Semir Zeki, a professor of neuroaesthetics (a department of Zeki’s own design focusing on the neural basis of aesthetics) at University College London, published their own study comparing passionate love and friendship in the fMRI scanner in the November 2000 issue of

Neuroreport

. Zeki was inspired by mentions of love in art. How often, in the throes of passionate love, have you thought that Rumi poem or Elvis Presley song must have been written for you? How many times have you looked at a painting and thought it represented a deep and true feeling you experienced? Think about all the descriptions of love that are out there—I mentioned quite a few in the introduction. Zeki believed that if the feeling could be captured and understood in these artistic contexts (or as a tire iron, as the case may be), there must be something common about love and other emotions inside each of us. Something that is an intrinsic part of our makeup, passed from generation to generation, that allows us to share similar emotional experiences. Otherwise we would not be able to recognize or connect with so many artistic expressions of love. He makes a compelling

point.

There is no question that the right visual image can elicit an emotional response. I’m only slightly embarrassed to admit that I am a reliable sucker for cute baby photos, AT&T commercials, and romantic comedy film trailers. And I am not the only one. The right picture, smell, or song can evoke commanding memories, along with any emotion behind them. Banking on that kind of power, Bartels and Zeki scanned seventeen folks who declared themselves to be passionately in love, eleven women and six men, while viewing facial photos of their significant other as well as photos of three other friends who shared the same sex as their beloved. The researchers instructed the study participants to simply look at each photo, think of the person in the photo, and relax. When they compared brain activation while viewing a lover and viewing a friend, they found two areas of the brain that reacted strongly: the left middle insula, an area implicated in emotion, self-awareness, and interpersonal relationships; and the anterior cingulate cortex, linked to reward anticipation, decision making, and emotion. And when they slightly lowered the threshold of activation, they also saw elevated blood flow in the hippocampus, the caudate nucleus, and the putamen, all areas involved with learning and memory, as well as the cerebellum, involved with the fine-tuning of motor control. It was a unique pattern, they argued, that could not be accounted for by anything but passionate love (though, Zeki quipped later, the brain activation pattern did look an awful lot like what you see in a brain after a hit of cocaine). What it meant, exactly, required further study.

5