This Is Your Brain on Sex (14 page)

Read This Is Your Brain on Sex Online

Authors: Kayt Sukel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Human Sexuality, #Neuropsychology, #Science, #General, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Life Sciences

Goldstein and her colleagues compared the activation of stress response circuitry (the amygdala, hypothalamus, hippocampus, brain stem, orbitofrontal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate gyrus) in men and women, both in the women’s fertile phase of their menstrual cycle and in the middle of the cycle, as they viewed a series of very unpleasant photos from a standardized photo set—think gory body parts after car crashes and the like. In women, the study showed different patterns of activation in this circuit between the two phases of their menstrual cycle. Women and men also showed distinctly different patterns of activation. But Goldstein says one of the most interesting things about this study was the fact that all participants reported having the same kinds of stressful feelings when they saw the photos.

6

Different brain activation, but similar feelings. How about that?

“We showed that hormonal status regulates the stress response in the brain differently at different points in the menstrual cycle in women,” Goldstein said. “Further, these hormonal differences explained sex differences in the brain’s response to stress, even in the face of no sex differences in the subjective feeling

of stress. This suggests that hormones are involved in maintaining homeostasis in the brain in response to stress.” Basically men and women experience stress in the same way, but their stress response involves different mechanisms in the brain.

I can’t help but notice that many of the brain areas in this stress response circuitry overlap with those activated by romantic love. But to date no one is looking specifically at sex differences in love, perhaps because the study of love is so new to neuroscience. But when I asked Goldstein about whether we might see gender differences in love and sexual relationships in the future, she reminded me of how important it is to be conservative when interpreting results from these kinds of studies.

“We know there are numerous sex differences in how the brain develops through childhood and then functions into adulthood,” she said. “But how these differences may or may not relate to complicated concepts like ‘love’ or ‘desire’ is unknown.” She paused for a moment before continuing. “The study of something like love is very complicated and cannot be reduced simply to the neuronal level. It can be thought of on many different levels, both conscious and unconscious, involving everything from emotion to cognition to physiology, psychology, sociology, and ‘chemistry,’ just to name a few.”

When I spoke to Helen Fisher about her neuroimaging studies, she said it would be interesting to take a closer look at gender differences in future neuroimaging studies of romantic love. “People are quick to assume that men and women are very different in this regard, that men avoid commitment and women really want commitment. Certainly, from an evolutionary perspective, it’s equally beneficial for both sexes to have a committed partner to help raise offspring. But does the brain back that up? It is something we still need to look at.”

Let’s Talk about Sex

So the jury is still out on whether men and women approach love differently from a neurobiological perspective. But sex seems to be a no-brainer, pardon the pun. Common wisdom tells us that men and women are very different when it

comes to sex. Men are more visual, women are more emotional. Men are willing to have sex with just about anything that happens across their path; women are more selective when choosing sexual partners. And it is often thought that men pretty much want sex constantly, whereas women are more the sexual camel type, able to go without intercourse for quite some time without a problem. This is what we often hear, anyway. If these particular stereotypes hold true, you’d think there’d be some neurobiological evidence to back them up.

Compared with other visual images, sexual images seem to produce a special effect on brain activation, in both men and women. “When we put people in the magnet and show them sexual stimuli, the response in the brain is two to three times stronger than any other kind of image or stimulus I’ve ever used,” said Thomas James, a neuroscientist at Indiana University who works with researchers at the Kinsey Institute studying sexual decision-making processes in the brain. “Sexual photos are incredibly arousing images, just in the general sense of arousal. They really get the brain going.” Even if those images do not result in direct sexual arousal, as indicated by noticeable erection or vaginal lubrication, brain activation still goes wild. Our brains, apparently, are fine-tuned for porn.

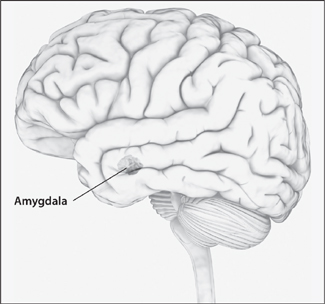

Are there different reactions between the sexes when viewing those sexual images? Apparently so. Kim Wallen, my favorite rhesus-watching companion, and his colleagues at Emory University noted that men seem more responsive than women to visual stimuli of an arousing nature. When they put both men and women in the fMRI and showed them a variety of kinky pictures, both had similar activation patterns in the reward circuitry. But the left amygdala, an area of the brain responsible for attaching context and meaning to the outside environment, showed significantly more blood flow in men than in women. Limbic regions, correlated with emotional responses, and the hypothalamus, that seat of sexuality, also showed greater activation in the men. Out of all those variations in cerebral blood flow, Wallen and his colleagues homed in on the difference observed in the amygdala and argue that this area may be responsible for the fact that men are more affected by visuals when it comes to sexual behavior.

7

The amygdala shows greater activation in males than in females when viewing sexual stimuli.

Illustration by Dorling Kindersley.

“What was really interesting to

me was that the women in this study actually subjectively rated the pictures as more sexually arousing than the men did,” said Wallen. “Yet we still saw higher activation in the men in the amygdala and hypothalamus. That says something.”

Heather Rupp, a former graduate student of Wallen’s who went on to the Kinsey Institute after leaving his lab, argues that the general neural circuitry that underlies sexual arousal is probably pretty similar in men and women. But, she maintains, those circuits may be differentially activated depending on the kind of stimulus presented.

8

That is one explanation. A good one too. Of course, there is an alternative hypothesis. Just because people are looking at duplicate photos does not mean they are paying attention to the same elements. Consider a good piece of porn, film or photo; there is usually quite a bit going on there. What if the dissimilarities observed in brain activation were due to the fact that people were just attending to different information?

Rupp and Wallen had fifteen men, fifteen women on the birth control pill, and fifteen women not using hormonal birth control view hundreds of sexual photos from free porn websites. As each photo was displayed, participants were asked to rate the sexual attractiveness of the photo with a number rating,

0 being the least attractive and 4 being the most attractive. If they found the image completely unattractive, they could give the photo a rating of -1; when that happened, the photo was not included in the analysis.

While the study participants made their sexual attractiveness decisions, the researchers recorded not only how long each participant viewed each photo but, using eye-tracking software, where exactly they were looking. Rupp and Wallen found a few interesting things. First and foremost, there was no significant difference between men and women in their subjective ratings of the stimuli or how long they looked at them. They were even as far as these two measures go, which disproves the idea that women do not appreciate visual sexual stimuli; women kept up with the men in terms of both ratings and view time.

Second, despite the fact that men and women showed appreciation for the porn, the two groups were not looking at the same things in each photo. Women tended to rate as more attractive those photos in which the female actors were looking away from the camera. But men did not seem to care which way the female actors were looking. Neither gender bothered to look too long at genital close-ups, but it was only men and women on oral contraceptives who rated them as significantly less attractive. Thus there were differences—sex-specific preferences—even when, across the group of stimuli, men and women chose similar ratings on the attractiveness of photos.

9

Once again, context matters.

Cognitive and behavioral studies have suggested several other key differences between the sexes. When researchers at the Sexual Psychophysiology Laboratory of the University of Texas at Austin looked at how well individuals remembered sexually relevant information in an erotic story, they found gender differences. Sex differences in cognitive tasks are often assumed to correlate with differences in neural activation. Previous studies had suggested that men were more likely to recognize specific erotic sentences—more quickly too—than women. But women were more accurate at recognizing romantic sentences that appeared in the text. In recall studies, men often erroneously remembered things from the story, of both a sexual and a romantic nature. To suss out what was going on, Cindy Meston, head of the Sexual Psychophysiology Laboratory, and her colleagues had seventy-seven undergraduates read a sexual story and then perform

a memory task. In this study men were more likely to remember the erotic elements of the story, and women were more likely to recall the specific characters as well as the love and emotional bonding bits. Here the participants played straight to stereotype.

10

When I asked Meston if she believed there might be a variation of neural activation underlying these differences, as many researchers assume when they see a disparity between the sexes in cognitive tasks, she paused before responding. “I do not know,” she said. “One could make the argument that erotic cues are more rewarding for men than [for] women, that perhaps a man gets a bigger dopamine burst when he sees an erotic picture or reads an erotic story. But I really do not know what we would see in terms of brain activation.”

Sexual Motivations

Men and women show different amygdala and hypothalamic activation. They don’t look at the same things in sexual photos. They remember contrasting details from erotic stories. What about sexual motivations? Do men and women have separate reasons for having sex?

Meston’s lab recently examined that question. In a large sample questionnaire study, she and her colleagues looked at all the reasons folks from eighteen to seventy might have for getting busy. The results surprised them. “You always hear that women are more likely to have sex for love, men for physical gratification. And we did see some of that,” said Meston. “For example, men were more likely to engage in opportunistic sex and women in sympathy sex. But across that age range, we found many more gender similarities than differences. The top three reasons for having sex were the same in both genders—they were having it for love, for commitment, and for physical gratification.”

You heard it here. Sure, gender differences are seen in a variety of studies. Many of them support the ideas we have about the ways men and women view sex. But there are a lot of similarities there too. Subjective reports of arousal, our reasons for having sex, show a lot of overlap between the genders.

“Some of these differences may be explained simply by differences in anatomy,” said Meston. “Anatomically, men get an erection when they are aroused. That is a pretty hard

thing to ignore. It is a strong, apparent signal grabbing his attention, probably distracting him from other things that he may need to get done. With women, the sexual response is tucked away, and the vagina does not hold as much blood as the penis. It may not be as strong a signal. So in this case, it may be what is going on in the rest of the world that is the distraction, not the arousal itself. Those anatomical differences might explain a lot of the gender differences you hear about.”

Love Remains the Same

What about love itself? Is what I experience when I feel love qualitatively different from what a man experiences? If I consider Semir Zeki’s hypothesis that literature and art across the ages show a common substrate for love in the mind, I might suggest that descriptions of sex by male and female authors and artists are sometimes different. But descriptions of love by writers of both genders? They aren’t all that dissimilar.

Although previous neuroimaging studies of romantic love by Zeki and Fisher included members of both sexes, a precise comparison of brain activation between the two was not undertaken. Zeki and his collaborator John Paul Romaya decided to take a closer look to determine whether there were gender differences in the way men and women experience love.

11

They compared cerebral blood flow in twenty-four people in committed relationships who claimed to be passionately in love (and scored high enough on a passionate love questionnaire to back that claim). Twelve of those participants were men, and six of those men were gay. The remaining group of twelve women was also made up equally of gay and straight women. The study paradigm was identical to Zeki’s initial romantic love study: each participant’s brain was scanned as he or she passively viewed photos of his or her partner and a familiar acquaintance matched in gender and age to their true love.