This Great Struggle (43 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

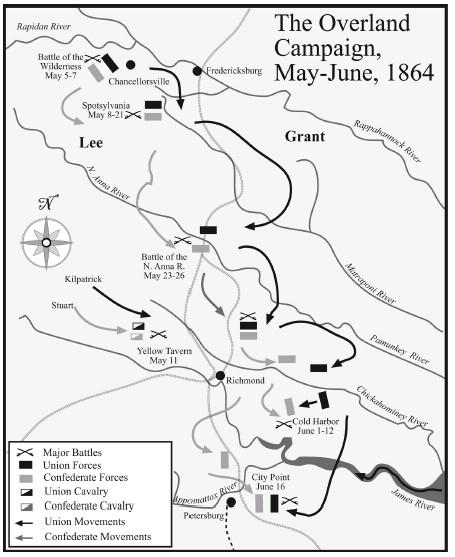

Instead of pulling back on first contact with the enemy as Hooker had done the year before, Grant drove straight at Lee. Intense fighting raged in the thickets the rest of that day, and the next morning, May 6, Grant launched a renewed attack that crumbled Lee’s line and threatened to break the Army of Northern Virginia in two. As Lee personally attempted to rally his troops and all seemed lost, two fresh Confederate divisions arrived on the battlefield: Longstreet’s troops, which had missed the first day’s fighting while marching up from their camps some distance from the rest of the army. At the head of Longstreet’s column was the hard-hitting Texas Brigade. As the Texans formed a line of battle in preparation for launching a counterattack, Lee in desperation rode his horse into position to lead the charge. Appalled, the Texans began shouting, “Lee to the rear!” and, crowding around his horse, finally turned its head and led it to the rear. Officers and men promised the general they would drive the Yankees back if only he would retire to a place of relative safety. Reluctantly, Lee did so. The Texans, joined by the rest of Longstreet’s corps, were as good as their word and halted the Union offensive after hours of bloody fighting.

On the other side of the lines, Grant had to contend not only with Lee and his army but also with the bad habits and defeatist attitudes ingrained in the Army of the Potomac since its inception under McClellan. Toward mid-morning that day a distraught general rushed up to Grant’s headquarters group exclaiming that he had seen all this before and knew just what Lee was going to do next, with the implication that it would mean disaster for the Army of the Potomac. Grant had heard enough of this sort of talk. “Oh, I am heartily tired of hearing about what Lee is going to do,” he barked. “Some of you always seem to think he is suddenly going to turn a double somersault and land in our rear and on both our flanks at the same time.” He sent the general back to his command with the admonition not to spend so much time thinking about what Lee was going to do to them but instead to start thinking about what they were going to do to Lee.

2

In fact, later that day Lee did launch successive attacks against both of Grant’s flanks. Each scored some limited local success, but after falling back a short distance the experienced Federals halted their Confederate pursuers and established firm new defensive positions. The thickets that had aided the Rebels by masking their movements proved a hazard as well. As Longstreet that afternoon attempted to regroup his command in order to follow up the initial success of his attack on one of the Union flanks, some of his own troops, hearing the headquarters group approaching through the dense underbrush, fired blindly, giving Longstreet a severe neck wound and killing or wounding several of his key subordinates. Lee’s most experienced corps commander would be out of action for months.

Meanwhile Grant, true to his word, wasted little time worrying about Lee’s efforts and slugged away at the Army of Northern Virginia with attacks of his own. By the end of the second day’s fighting, the result of this clash between the war’s two most successful commanders was a draw, though the Union, with the larger number of troops it had in the Wilderness, had suffered correspondingly more casualties. Grant could afford this. Lee could not, but Grant had no intention of winning the war by attrition by pushing both armies into the meat grinder of battle until his was the only one left. As Grant’s Vicksburg campaign clearly demonstrated, the tenacious Union general favored maneuver over human erosion. Nevertheless, if that was the only advantage he could gain from the Battle of the Wilderness, as it came to be called, he would grimly take it and keep moving on.

Rather than keep feeding the meat grinder in the tangled forests of the Wilderness, Grant decided to slide eastward around Lee’s right flank and seize the crossroads hamlet of Spotsylvania Court House, which would put him between Lee and Richmond. If the move succeeded, Lee would have to fight the more powerful Army of the Potomac at a severe disadvantage. Grant put his army in motion on the evening of May 7.

For the private soldiers in the Army of the Potomac, with their extremely close-up perspective on the battle they had just fought, the combat of the past two days did not seem all that much different from that of Chancellorsville or any of the other bloody and indecisive defeats the army had suffered at Lee’s hands during the past two years. As the column marched away from the positions it had held in the still-smoking Wilderness, the men remained uncertain as to whether they had won or lost and whether their march was an advance or a retreat. The answer came when the head of the column approached a crossroads where it had to turn either north or south. As the lead regiment reached the crossroad, its officers turned it south, away from the Potomac and retreat and toward Richmond and an ultimate victory that many of the marching men would not live to see. Despite the prospect of another immanent bloody meeting with Lee’s army, the men of the Army of the Potomac waved their caps and cheered at the realization that they had fought a battle and were still advancing.

The private soldiers of the Army of the Potomac had never been the problem; under McClellan, Burnside, Pope, or Hooker they had always been ready for hard fighting. But that night’s march demonstrated that the army’s command and staff still made it the clumsy instrument McClellan had forged in the camps around Washington in the fall of 1861. Two and a half years of futility had reinforced the cautious, deliberate habits of the officers who maneuvered the army. As an organization it had never developed the quick, supple efficiency of Grant’s old Army of the Tennessee. In the case of the present movement from the Wilderness to Spotsylvania, the cavalry that was supposed to lead the march somehow did not arrive in time, and the supporting infantry was slow in coming up.

As always, Lee was quick to make his opponents pay for such sloppy performances. With the aid of excellent intelligence from his chief of cavalry, Jeb Stuart, the Confederate commander correctly anticipated Grant’s target and quickly put his own troops on the march. The Army of Northern Virginia moved with the speed Grant had come to expect from his own troops out west but was frustrated to find he could not obtain from the Army of the Potomac. The result was that by the time blue-clad troops arrived in force in the vicinity of Spotsylvania Court House, they found solid Rebel lines blocking their path.

The Rebels had entrenched, as both Union and Confederate troops were by this stage of the war quick to do both here in Virginia and down in Georgia. Any place a unit of infantry halted for more than a couple of hours, the troops dug trenches and felled trees to make obstructions (abatis, as they were called in the military parlance of the time) out of their tops and added their trunks to their breastworks. The practice had begun in relatively isolated cases in late 1862 and had spread throughout 1863. By 1864 it was virtually universal. Breastworks multiplied the already heavy advantage of the defender. A well-dug-in defending force could now be reasonably confident of repulsing several times its number of attackers and inflicting ghastly casualties while doing so, a fact that did much to shape the conduct of the 1864 campaigns in both Virginia and Georgia.

Grant brought the Army of the Potomac up against Lee’s extensive Spotsylvania breastworks and struck at them to make sure the Rebels were truly present in strength. They were, as the Union soldiers paid the price in casualties to find out. The frustration was bitter at Grant’s headquarters and those of the Army of the Potomac. Meade blamed the Army of the Potomac’s new cavalry commander, Philip Sheridan, whom Grant had snatched from a division command in the Army of the Cumberland and brought with him to put some drive and fire into the eastern army’s horse soldiers. Sheridan said it was Meade’s fault for hamstringing his command and detaching much of its strength with assignments like shepherding supply wagons. Turn him loose with all his cavalry, he said, and he would whip Jeb Stuart. Both Meade and Sheridan were known for their irascibility, and the interview was a stormy one. The seething Army of the Potomac commander referred the matter to Grant, complaining of Sheridan’s preposterous boast that he could whip the legendary Stuart. To Meade’s surprise and disgust, Grant responded wryly, “Did Sheridan say that? Well, he generally knows what he is talking about. Let him start right out and do it.”

3

So on May 9 Sheridan took his ten thousand troopers and set out southward, directly toward Richmond, marching in a column that sometimes stretched as long as thirteen miles. Among his goals were tearing up the railroad behind Lee and threatening Richmond, but both of these were for the purpose of accomplishing the expedition’s chief goal: gaining a showdown with Jeb Stuart and whipping him. That showdown came two days later, six miles outside of Richmond, near a derelict inn called Yellow Tavern. Stuart met Sheridan with 4,500 men, and a four-hour battle ensued. When it was over, Sheridan’s squadrons had succeeded in brushing past the Confederate horsemen who had tried to block them, but, more importantly, Stuart had taken a .44-caliber pistol bullet in the abdomen and died the next day. Sheridan wisely chose not to challenge the stoutly built Richmond fortifications, even lightly manned as they were. Instead he rode to Butler’s nearby lines at Bermuda Hundred to rest and resupply his command before riding back to rejoin Grant on May 24. The raid had deprived Grant of cavalry scouting for two weeks but deprived Lee permanently of the services of Stuart, perhaps the best scouting cavalry commander of the war and already a legend throughout the South.

THE BATTLES OF SPOTSYLVANIA COURT HOUSE AND THE NORTH ANNA RIVER

Meanwhile back at Spotsylvania Court House, Grant continued to probe for weaknesses in Lee’s position. During the course of May 10, units of the Army of the Potomac made local assaults on several sectors of Lee’s heavily entrenched lines. Most were dismal failures, but one showed promise. A young colonel named Emory Upton believed he knew how to defeat the ubiquitous entrenchments. Arranging twelve picked regiments one behind the other, he had them charge full speed toward the Confederate breastworks without pausing to fire. As he hoped, this overwhelmed the defenders of a narrow section of entrenchments, and his attacking column broke through. The assault ultimately failed, however, because of the difficulty of exploiting a breakthrough once made.

Grant was intrigued by Upton’s effort. The sector the colonel’s column had struck looked particularly vulnerable, a protruding bulge, or salient, in the Confederate line that the soldiers had nicknamed the Mule Shoe because of its shape. It allowed a large concentration of Confederate cannon there to get a crossfire on Union troops approaching either end of Lee’s line, but it was itself vulnerable to direct attack, especially if that attack converged from all sides of the salient. That was exactly what Grant planned to do, using Upton’s tactics with a whole corps instead of a mere twelve regiments. The army spent May 11 in preparation.

The attack went in as scheduled in the predawn hours of May 12. For once Lee had guessed wrong about what an opponent would do next. Thinking that the quiet on the eleventh portended a Union withdrawal, perhaps in preparation for another lunge to the east, Lee had begun to pull his army back in preparation to sidle east himself to counter Grant’s presumed next move. The first step was pulling the cannon back out of the Mule Shoe. Their crews had just limbered up and pulled out of their emplacements when Grant’s massive assault sent the twenty thousand men of the Army of the Potomac’s Second Corps storming over the breastworks, capturing four thousand defenders; their division commander, Major General Richard Johnson; and the cannon, whose crews did not have time to unlimber again and fire.

As with Upton’s attack two days before but now on a much larger scale, the assaulting force struggled to overcome the disorganization generated by its successful advance. While its officers strove to untangle its ranks and get it moving forward again, Lee rushed Major General John B. Gordon’s division into the Mule Shoe to plug the hole in his line. Once again in desperation Lee moved into position to lead the charge personally, but his troops would have none of it, again shouting, “Lee to the rear,” as the Texans had done six days before and refusing to advance until he had drawn back to safer ground.

With their army commander out of the way, Gordon’s men surged forward and struck the disorganized Yankees of the Second Corps, driving them back to the breastworks. Determined to hold the gains they had made, the Federals pushed back, and a frenzied hand-to-hand struggle raged across the breastworks, Federals on one side, Confederates on the other, the two lines standing within arm’s reach of each other, shooting, bayoneting, and clubbing with a ferocity that seemed scarcely human. As both sides pressed reinforcements to the embattled section of parapet, the battle raged on for hour after hour. Tens of thousands of rifle bullets hissing past their intended targets mowed down the foliage just behind the lines and whittled through the bolls of trees a foot thick, while enough of the bullets found their marks to pile bodies two or three deep or more for scores of yards on either side of the breastworks. Near the center of the disputed barricade, the breastworks made a sharp corner, and that feature gave its name to this particular part of the Battle of Spotsylvania, which would thereafter be remembered as the Bloody Angle.