This Great Struggle (37 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

On the other side of Cemetery Ridge, the Confederate preparatory bombardment lifted, and Longstreet’s three divisions of infantry advanced in the long, straight ranks that were the standard fighting formations of the Civil War. The open farmland of the shallow valley between the armies gave a rare opportunity of viewing eleven thousand men in such formation, and it was an impressive sight. Long-range Union artillery tore at the Confederate lines as they marched steadily forward. Then when they were about three hundred yards from the Union lines, the batteries opened up on them with canister, and the Union infantry added their rifle fire, mowing down hundreds of attackers.

The Confederates pressed on to within a few yards of the Union line and in one place actually drove it back a few yards, several hundred gray-clad soldiers stepping over the low stone wall the Federals had held in that sector and occupying a small copse of trees that was the only landmark in that open stretch of ridge. Then Union reinforcements surged forward and overran them, sending the rest of the Confederate attackers stumbling back toward their starting point three-quarters of a mile away. Longstreet’s grand assault, often called Picket’s Charge, after one of the three division commanders, was over.

So too was the Battle of Gettysburg, though the participants were not yet aware of the fact. Lee expected that Meade would counterattack. He did not, and the armies spent the next day at a standoff. During the days that followed, as Lee retreated back to the Potomac and especially when he and his army were temporarily trapped on the north side of the flood-swollen river, Lincoln desperately hoped that Meade would follow up his victory with an aggressive pursuit that trapped and destroyed the Army of Northern Virginia. Instead Meade followed cautiously and paused long enough for Lee to get across the Potomac, much to Lincoln’s disgust. Meade had his reasons. He had been in command scarcely more than a week, and his army had taken severe losses, including three of its seven corps commanders. Lee’s army, though beaten, would still have fought well on the defensive. Lincoln’s frustration was understandable since decisive results seemed to beckon, but, as usual in the eastern theater of the war, those results remained just out of reach.

Curiously, in view of all this, Gettysburg stands in the popular imagination as the great decisive battle and turning point of the war. In fact, it was nothing of the sort. It was not even a turning point within the indecisive eastern theater of the war. Militarily it was just one more bloody and inconclusive clash of the armies, full of sound and fury and acts of sublime heroism on both sides but bringing the end of the war not one day closer.

From the time Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia at the end of May 1862 until the time Grant took over direct operational supervision of the Army of the Potomac at the beginning of May 1864, a complete deadlock existed on the war’s eastern front. During that time, everything south of the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers was Confederate territory and everything north of those streams Union. From time to time one army or the other would strike its tents and make a foray into the other’s territory. A bloody battle might result, as had been the case at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg, or the armies might maneuver around each other in a menacing minuet without coming to the point of mass bloodletting, as was to be the case with the lesser-known Bristoe Station and Mine Run campaigns in the second half of 1863. Either way, when each campaign was over the armies returned to the positions they had held before it started. In those six campaigns Lee had crossed the Rappahannock on the offensive three times, and his enemies had crossed it on three of their own offensives, and the results, other than several tens of thousands of men killed or wounded, was to demonstrate that with the present commanders and relative sizes of armies an almost perfect balance existed. Lee could not remain north of the Rappahannock, and his enemies could not remain south of it.

The only difference with the Gettysburg Campaign was that Lee’s army returned to Virginia with many new horses and several months’ worth of a much-needed supply of food that it had plundered from the civilian population of Pennsylvania. It also brought along perhaps a hundred or so Pennsylvanians of African descent whom it had kidnapped and carried south to be sold into slavery. It is ironic in the extreme that Confederate propaganda, both during the war and since, succeeded in establishing as fact the myth that Lee’s noble soldiers left civilians and their property untouched during their march to immortality at Gettysburg, in contrast to the blue-clad “Yankee vandals” in their marches through the South. The real contrast was that the “Yankee vandals” did not kidnap civilians.

DECISIVE UNION VICTORIES IN THE CONFEDERATE HEARTLAND

While the Gettysburg Campaign took its ultimately indecisive course in the East, momentous events were taking place in the Mississippi Valley. Day after day Grant’s siege lines pressed closer and closer to the Vicksburg defenses until by the first days of July they were in many places within a dozen yards or so of the Rebel parapet. Twice during the siege Union troops tunneled under the Confederate fortifications and set off massive powder charges, hurling men and guns through the air, along with the logs and earth of which the fortifications had been constructed, and leaving yawning craters where stout bastions had been. Each time, Confederate reserves moved up to hold the line and prevent a Union breakthrough. Yet as Grant’s approach trenches crept ever closer and food inside the city grew ever scarcer, it became increasingly clear that a coordinated Union assault would soon strike the entire Confederate perimeter at the same time and that Pemberton’s troops would have little or no chance of stopping it. The gray-clad defenders could not know it, but Grant had set July 7 as the day for the assault.

It never came to that. On July 3, as Pickett’s division was preparing for its march to immortality half a continent away at Gettysburg, Pemberton requested surrender negotiations. Grant agreed to accept the capitulation of Pemberton’s thirty thousand troops and then to parole them, a practice common during the war up to that time. Prisoners would give their parole—their word of honor—that they would not take up arms again until they had been officially exchanged by the release of an opposing soldier from prison or from his own parole. It was, quite literally, an honor system for prisoners of war, and the amazing thing was that it had worked up until that point in the conflict. Captured soldiers were thus spared the misery of months or years cut off from family in an enemy prisoner-of-war camp, while the captors were spared the burden of transporting and maintaining them. The system could work as long as each side, especially the one with more paroled prisoners, placed the value of honor above the value of the military advantage that might be gained by the early release of its troops. That situation ended with the enormous surrender at Vicksburg. Confederate authorities promptly and illegally returned the thirty thousand men to duty without exchange. With that, the parole system was over since Union commanders could not henceforth trust the Confederates to keep their word. As a result, prisoner-of-war populations began to grow steadily on both sides.

The surrender ceremony at Vicksburg took place on July 4 as Lee was beginning his retreat from Gettysburg. Three days later, having heard of Vicksburg’s surrender, the subsidiary Confederate bastion at Port Hudson, Louisiana, surrendered to besieging Union forces under Nathaniel P. Banks. The twin victories severed the Confederacy from its trans-Mississippi resources and reopened the river as an artery of Union commerce, enabling Lincoln to note in a speech a few weeks later, “The Father of Waters goes again unvexed to the sea.”

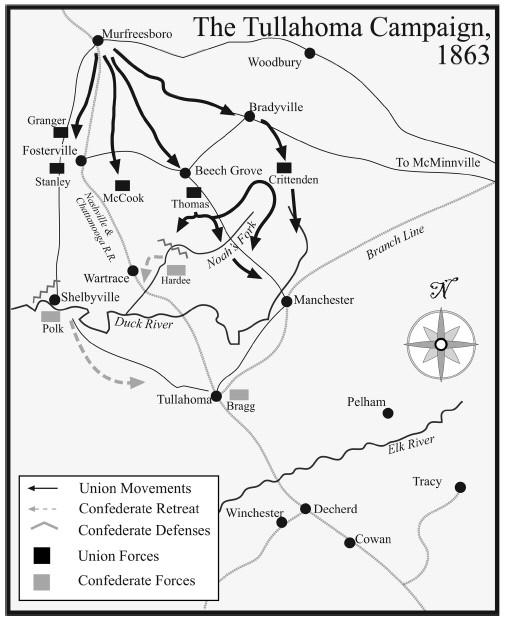

Meanwhile another Union army had scored a significant success within the Confederate heartland. In a nine-day campaign in late June and early July, Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland, after months of urging by the authorities in Washington, had finally moved and had maneuvered Bragg’s Army of Tennessee almost out of the state whose name it bore, all the way from Tullahoma, near the center of the state, back to Chattanooga, a handful of miles from the Georgia line. Bragg, handicapped by dissension among his subordinate generals almost to the point of mutiny, was unable to counter effectively. The campaign produced no major battle and only a few relatively minor clashes between small detachments. Yet, though it was less significant than Vicksburg, it was much more significant than Gettysburg since it transferred thousands of square miles of formerly Confederate territory firmly and permanently into Union control, inflicting a severe loss on the Confederacy in agricultural production, recruitment, and morale. In one sense, however, the Tullahoma Campaign was more like Gettysburg than Vicksburg. It left the defeated Confederate army intact and able to fight another day, as the Federals would learn with sorrow three months hence during the bloody Chickamauga and Chattanooga campaigns.

Nevertheless, the Union armies had scored major victories on all three main fronts of the war, along the eastern seaboard at Gettysburg, in Tennessee in the form of the Tullahoma Campaign, and most significantly at Vicksburg, where Grant’s victory had secured the Mississippi Valley under Union control. In a letter to be read at a public rally in Illinois that August, Lincoln reviewed the recent victories and those who had fought to achieve them. Then he concluded, “Thanks to all. For the great republic—for the principle it lives by, and keeps alive—for man’s vast future—thanks to all. Peace does not appear so distant as it did. I hope it will come soon, and come to stay; and so come as to be worth the keeping in all future time.”

2

9

“THE UNFINISHED WORK”

STRESSES AND TURMOIL ON THE CONFEDERATE HOME FRONT

A

s the war entered its third year in the spring of 1863, civilian populations on the home fronts felt its pinch with ever increasing sharpness. In the South, the effect of the war was felt not only in the absence in the army of more than one third of the region’s white male population but even more directly in the growing shortage of food, especially in urban areas and near the fighting fronts. This was ironic because the South was an overwhelmingly agricultural region. At the outset of the war, Jefferson Davis had appealed to planters to shift from cotton to food production, but most had thumbed their noses at his request since cotton was a more lucrative crop. Indeed, if it could be run through the Union blockade on one of the sleek, fast, purpose-built blockade-running vessels that British shipyards were soon turning out, cotton offered bigger profits than ever in the markets of Europe. Yet despite the continued devotion of vast acreages to the white fiber, the South still produced enormous amounts of food, amounts that should have been adequate to feed its people. Why then was hunger stalking significant segments of its population?

One reason was the lack of transportation to move the food from where it was grown to where it was to be consumed. Although the South’s rail network had grown rapidly during the 1850s, it was still fragmented and partial. Very few trunk lines carried rail traffic from one southern region or state to another. Most of the South’s railroad tracks had been laid down with a view to carrying cotton and other produce from interior areas to ocean or river ports whence it could be shipped to the markets of the world. Few of these small rail systems connected with each other, and it would have done little good if they had since many had incompatible gauges (width between rails), and thus their rolling stock could not move on another railroad’s track.

The war made the South’s railroad transportation system worse. Each side tore up the other’s railroad tracks when it could reach them. Sometimes retreating Confederate forces tore up their own tracks to prevent advancing Federals from using them for supply lines. Sometimes the Confederate government disassembled a section of track in order to use the iron rails for the construction of ironclads, few of which, like the

Virginia

, were completed before the Federals could seize them and none of which enjoyed even the

Virginia

’s brief success. The iron that plated their incomplete forms or that lay stacked beside the dry dock awaiting application might well have served the Confederacy better as rails. Thanks to the shortage of transportation, food tended to stay in the agricultural districts where it grew rather than finding its way in sufficient amounts to the cities and fighting fronts where the need was greatest.