This Great Struggle (15 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

Throughout the war Grant would develop a pattern of being the man who accomplished things that others had only thought about doing. One reason was his persistence, usually aimed at the enemy but this time, of necessity, plied on his superior, Halleck. A couple of weeks later, he proposed his idea to Halleck again. This time the situation had changed enough to win Halleck’s approval. Lincoln’s General War Order Number One had reached Halleck’s desk, and letting Grant off the leash for a few days might be a good way to satisfy the president and relieve the pressure. Then word arrived from Washington that a recently captured Confederate soldier had reported that Beauregard was coming from Virginia to Tennessee with fifteen regiments of troops. The Creole general was indeed on his way, but the part about the regiments was wrong. Beauregard did not have fifteen staff officers with him and no troops at all. Still, the threat that Confederate reinforcements were about to arrive and make future offensive operations much more difficult was the final prod Halleck needed to turn Grant loose.

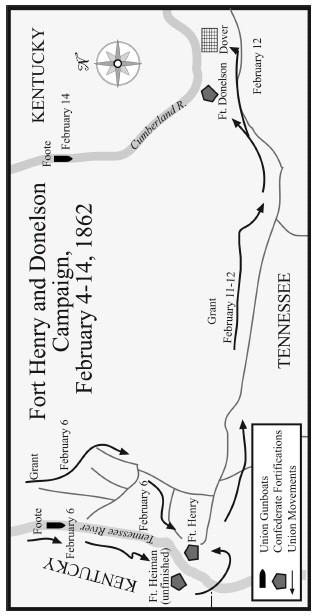

Grant loaded his army, now grown to seventeen thousand men, into steamboats and set out from his bases at Cairo and Paducah on February 3. The next day the first elements of his force began landing on the banks of the Tennessee River several miles downstream from a Confederate outpost called Fort Henry. Begun during the days of Kentucky neutrality, Fort Henry was located near the river’s northernmost point in the state of Tennessee. It was a poor location for a fort, but Kentucky was unavailable, and Tennessee planners wanted to protect as much of their state as possible. Worse, the fort had been under Polk’s jurisdiction since the preceding summer, and Polk, with his fixation on Columbus, had accumulated most of his department’s troops and both of its trained engineer officers at the Mississippi River stronghold, leaving Fort Henry undermanned and incomplete even after Johnston, who had been Polk’s West Point roommate, sent him repeated orders to see to it that the fortifications on the Tennessee were in good shape. Now the poorly sited, incomplete, undermanned fort was all the Confederates had to prevent the deep penetration of the Confederate heartland via the Tennessee River.

After scouting the fort from a distance, Grant gave orders that the assault should take place at 10:00 a.m., February 6. His troops marched out of their camps that morning in high spirits but were soon dismayed to find that recent rains had turned the dirt roads of Tennessee into seemingly bottomless quagmires. Laboriously they waded on through the mud, dragging their artillery, caissons, and ammunition wagons, but when 10:00 came they were still far from their attack positions.

Cooperating with Grant’s force on this operation was a squadron of four of the navy’s new ironclad river gunboats under the command of Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote. Another of the navy’s crusty, old seadogs, the tough, aggressive Foote was a stickler for precision. Grant had asked him to attack at 10:00 a.m., and that is exactly what Foote did, leading his boats into action with colors flying and guns blazing.

The gunboats were strange craft. Based loosely on the design of ordinary riverboats, they drew six to eight feet of water and were 175 feet long and a little more than fifty feet wide. A casemate, or box, covered nearly the entire deck space of each gunboat, enclosing its thirteen heavy guns and single, twenty-two-foot-diameter paddle wheel, driven by two steam engines mounted side by side in the vessel’s shallow hold and capable of propelling the gunboat at a respectable eight knots. The casemate’s sloping sides, along with the vessel’s overall squat proportions, led nonplussed observers to nickname them, after their designer Samuel M. Pook, Pook’s Turtles. The turtles’ shells were only selectively strong and then only within limits—two and a half inches of iron plate forward, an inch and a half on the sides and the small pilot house above the casemate, and none at all aft. No more of the heavy armor could be added to such a shallow-draft vessel.

The gunboats proved effective against Fort Henry. The fort’s commander had seen the handwriting on the wall and hastily dispatched almost his entire garrison to march the twelve miles east to Fort Donelson, the Confederacy’s outpost on the Cumberland River, something they were able to do because Grant’s troops were still stuck in the mud several miles away. Then with a small volunteer force he stayed behind to man the fort’s few cannon and delay the inevitable. One of their shots actually penetrated a gunboat, bursting its boiler and putting it out of action with heavy casualties, but the others came on. Then one of the Confederate cannon burst, mangling its crew; the gunboats closed in to point-blank range, and the fight was soon over. The Confederates raised a white flag, and since the river was in flood stage and the fort’s location was so low to the banks, a rowboat bearing a naval officer came right through the main gate to accept the surrender.

The fight had cost less than 120 casualties on both sides combined. Yet it was one of the most decisive battles of the war. The Union victory at Fort Henry tore open the center of the Confederate defenses in the West, leaving the way open for Union gunboats and Union troops to penetrate up the Tennessee River all the way into northern Mississippi and Alabama, and the Confederacy could do almost nothing to stop them. West Tennessee was lost to the Confederacy, and the next place the Rebels could hope to make any serious stand on the Mississippi River was now more than three hundred miles south of Columbus, deep in the state of Mississippi. The Battle of Fort Henry did not decide the outcome of the war in a single day—no battle could do that by itself—but the Confederacy never really recovered from it. The remainder of the war in the West represented a series of Confederate attempts to win back what had been lost—and Union attempts to exploit what had been won—in less than four hours on February 6, 1862.

FORT DONELSON

Grant intended to follow up quickly and make the Confederate disaster even more complete. If Fort Henry had fallen so easily, Fort Donelson would likely do the same, and this time Grant planned to see to it that he had his troops in position in plenty of time to bag every last Rebel in the place as a prisoner of war. On the day Fort Henry fell, Grant sent a dispatch to Halleck informing him of victory and adding, “I shall take and destroy Fort Donelson on the 8th and return to Fort Henry.”

It was not quite that easy. Heavy storms of rain, sleet, and snow swept across the Upper South for the next few days, rendering the roads once again impassible. By February 12 another sudden shift in the weather had brought clear skies and a warm sun that dried the roads and convinced many of Grant’s soldiers on the march that day to throw away their overcoats as useless burdens, convinced as they were that spring had come in February here in the sunny South and that the war would be over long before autumn. By the morning of February 14 Grant had his army in place surrounding Fort Donelson, from the Cumberland River below (north of) almost to the river above the fort. All that remained was for Foote and his gunboats to go in and blast the Rebels into submission as they had at Fort Henry eight days before.

The situation inside Fort Donelson was considerably different than that inside Fort Henry had been, in part because of decisions Albert Sidney Johnston had made after the fall of Fort Henry. From his headquarters in Bowling Green, Kentucky, Johnston had realized that the ironclad gunboats opened a new chapter in warfare, making the rivers into highways of conquest for the side that owned them, and his side owned none. He assumed that Fort Donelson would not hold out much longer than Fort Henry had lasted.

From there, the logic of Johnston’s decision was inexorable. He could not afford to abandon the fort without a fight because once it was in Federal hands, the Union gunboats would range up the Cumberland all the way to Nashville, cutting off his main body at Bowling Green. He needed a few days to get his troops back across the Cumberland at Nashville and continue the retreat southward. He did not want to sacrifice the garrison of Fort Donelson. He could not afford to lose a man unnecessarily if he was going to have a chance of retrieving Confederate fortunes in the West. He could not count on Grant to be slow again in surrounding the fort. So Johnston’s only hope of both buying time and ensuring the garrison’s escape would require inserting enough infantry into the fort to enable them to push the encircling Federals aside, break out, and rejoin the army somewhere south of Nashville.

The troops Johnston sent to Donelson were those he had on hand, close enough to reach the fort in time. There was a brigade under the command of Brigadier General Gideon J. Pillow, a Tennessee politician, political ally of the eleventh president of the United States, James K. Polk, and an ardent secessionist. A veteran of the Mexican War, Pillow was now serving as a political general in his second war. His past record did not inspire confidence—he had become notorious among U.S. officers in the Mexican War for having had his men construct a set of fortifications backward—but his brigade was available. Another available brigade belonged to another political general, former Virginia governor and U.S. secretary of war during the Buchanan administration, John B. Floyd. Widely suspected in the North both of financial graft while secretary of war and of deliberately transferring heavy cannon to southern arsenals on the eve of secession so as to make them easy pickings for the Rebels, he had been less effective for the Confederacy since he had put on its uniform, having contributed his part to the ongoing Confederate debacle in western Virginia.

Thus, Johnston sent what troops he could, and those included Pillow’s and Floyd’s brigades. By the time Grant arrived outside the fort, its defenders numbered about twenty thousand men. Floyd, as senior officer present in the fort, had the command. Grant’s force outside the fort numbered about seventeen thousand.

The morning of February 14 dawned bitter cold. Another front had passed over during the night, rain turning to sleet and then to snow, several inches of it, and temperatures dropping into the low teens. Too close to the enemy to light campfires, the soldiers huddled grimly under the icy blast. At the appointed hour, Foote led the gunboats into battle, and soon troops all the way around the Union and Confederate perimeters, out of sight of the river, could hear the constant thunder of the big guns. Federals were confident, Confederates almost in despair. “The fort cannot hold out twenty minutes,” Floyd wrote in a message to Johnston sent across the Cumberland as the gunboats closed in.

Then to everyone’s astonishment, the Confederate shot and shell began to take their toll on the iron behemoths. The key difference was that Fort Donelson was located on a high bluff, giving its guns the ability to fire down at an angle onto the unprotected wooden decks of the gunboats. One boat after another went out of control, steering shot away or boilers burst, and drifted helplessly back down the river, still pounded by the Confederate guns until it mercifully passed out of range. The flagship’s pilothouse took a direct hit, severely wounding Foote. Presently the last of the gunboats fell back down the river with heavy damage, and the fight was over. As the guns fell silent, stunned Union soldiers around the perimeter heard cheers starting in the Confederate positions near the river and running around the lines.

Grant took in stride the realization that his ground troops were going to have to take the fort with minimal help from the navy. He sent for additional troops from those he had left to garrison Fort Henry and settled down to prepare for either an assault or a siege. In the dark hours after midnight of another brutally cold night came a message from the wounded Foote asking if Grant could ride to meet him where the flagship and the other battered gunboats were tied up several miles below the fort. Though his message did not say so, Foote needed to explain to Grant that the fleet was going to have to withdraw to Cairo for repairs. Grant appreciated the voluntary cooperation of Foote, whose naval command had never been under Grant’s orders. Eager to repay the flag officer’s assistance, Grant agreed to go. He left no officer in command of his army but left strict orders with each of its three division commanders to remain in their positions and do nothing until he returned. One of the three was McClernand, a political general whom Grant had learned to distrust.

Grant was a general who devoted most of his thought to what he was going to do to the enemy and relatively little to what the enemy might be planning to do to him. He understood the value of momentum in warfare better than almost any other general on either side during the war, and he made a point of seizing and keeping it: “Get at the enemy as quick as you can. Hit him as hard as you can, and keep moving on.” As long as he kept the momentum he was by far the most dangerous general of the war, but when something happened to halt his momentum, whether enemy action or the orders of a superior, he became vulnerable. The repulse of the gunboats had put Grant in such a situation.

Grant had been gone only a short time, and it was still dark when the numb and shivering troops on the right end of the encircling Union line, near the Cumberland on the opposite side of Fort Donelson from where Grant was riding away, saw darker shapes moving toward them from the direction of the fort. The Confederates were attacking. In keeping with Johnston’s orders, having bought what they believed was enough time for Johnston’s retreat from central Kentucky, Floyd, Pillow, and fellow brigadier general Simon B. Buckner (West Point, 1844) had arranged their breakout attack, reducing troops to a minimum on the northern perimeter to mass every available man for an assault southeastward, with the Cumberland River on their left.