Thirty Rooms To Hide In (35 page)

Read Thirty Rooms To Hide In Online

Authors: Luke Sullivan

Tags: #recovery, #alcoholism, #Rochester Minnesota, #50s, #‘60s, #the fifties, #the sixties, #rock&roll, #rock and roll, #Minnesota rock & roll, #Minnesota rock&roll, #garage bands, #45rpms, #AA, #Alcoholics Anonymous, #family history, #doctors, #religion, #addicted doctors, #drinking problem, #Hartford Institute, #family histories, #home movies, #recovery, #Memoir, #Minnesota history, #insanity, #Thirtyroomstohidein.com, #30roomstohidein.com, #Mayo Clinic, #Rochester MN

And if there ever is one, I want it to be Grandpa Longstreet’s God, not Grandma Rock’s. I’d want a sunny god, with deep laughter like Grandpa’s, a god who comes in at the last minute and makes everything right and tells me that if I look up into the dark rafters right now I’d see my dad’s faint outline floating there like a firefly, friendly and clear, and then Dad would come down to me. As he descends to our pew he’d see my smile – my eyes like landing lights and he’d know right away all was forgiven, everything – the gun, the axe, the BOOM! on the library door – don’t you see? none of it will count if you can just pull off this one trick and come down to talk to me one last time.

As Mom whispers her Greek alphabet and Uncle Jimmy squeezes her hand, the sun angles down from the high stained glass windows like a banister and down the stairs Dad comes, slowly, as if doubtful all he’s done can be wiped clean with one fantastic appearance in a church but it is, Dad, it is, and he floats closer and I see he’s skinny again and his eyes, oh they’re so focused and clear and they’re full of fierce love and then of tears as he surrounds me, the soft crackle of starched white shirt, the smell of Old Spice and a whispering, I’m sorry, so sorry for everything. I love you, I’ve always loved you, and he looks down the pew at a line of six little boys he once kissed on the head one by one in a sunny dining room long ago and finally he sees the beautiful Florida girl at the end, no longer in her black funeral dress but in the bright citrus colors of her Momma’s homemade clothes, sees her big white pearly button earrings and remembers how brightly “The Gypsy” stood out on that drab Midwestern campus of 1942.

He whispers, tell your momma I love her. And tell all your brothers, each one, I love them all. Tell them I’m sorry, for everything.

And presently the scratch of his cheek eases and he’s up the sun stairs again, waving, says he’s going back.

“Back to a place I know where the sand is white, the sun is hot, the palm trees whisper and the Gulf of Mexico is green and clear. Your mother and I went swimming there 30 years ago. I might even dig up a fishing pole.”

You tell them now, don’t forget, tell them, okay?

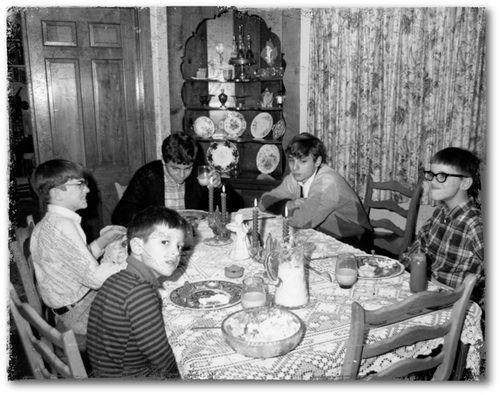

In the dining room sometime right before Dad died.

Clockwise from front: Colly, Chris, Kip, Jeff and Luke

Mom, July 31, 1966

Dearest Mother and Father: Four weeks have passed – and it’s still July. I’ll be glad to be rid of this month. 1966 is more than half over and has not turned out to be the year we expected it to be. The long struggle is over (for both Roger and me). And my problems have been reduced to two – one an old one, one new. The new one is to learn to live on much less money; selling this wonderful old house will help with that. The old one is the harder – to raise to manhood six boys whose lives have been full of violence, uncertainty, hate and neglect. It won’t be easy.

Being twelve years old in Rochester, Minnesota, in the summer of ‘66 was a good thing. There had been family trauma for nearly ten years, yeah, but nobody’d

died

. Well, not counting my dad, but the point is we were all alive, the seven of us – the ten actually, if you count Pagan and my hamsters.

On one level, it was kind of cool having a dead dad. At school, I was able to strike some seriously sad poses for Debbie Laney, leaning against the bike rack with a look that said, “Yep. My dad died. Pretty sad. Me? Nahhh, I’ll be all right. Maybe I’ll see ya ‘round then.” I’d walk away (in slow motion, of course) employing the Lonely-Guy-On-Cold-Street walk. Lonely Guys aren’t supposed to turn around to see if they’re being watched, but if they were, I would’ve walked backwards for

blocks

yelling back to Debbie, “STILL DEAD, MY DAD IS. YEP. FEELIN’ PRETTY SAD!”

The Beatles’ new album

Revolver

was #1 on the charts and all the films of my fantasy life were now scored with Harrison’s

Taxman

. Paul McCartney’s joyful numbahs one-two-three-FAH! had matured into George’s deadlier count-off, intoned like a mortician and followed by a guitar riff a Lonely Guy could nicely time his steps to as he walked down the hallways of Central Junior High School.

I turned to smoking cigarettes full-time and posing for effect at every opportunity. For my birthday, Mom bought me my first bike, a Sting Ray with Banana Seat and Ram’s Horn handlebars. I would ride this fantastic machine to the YMCA downtown and Lonely-Guy my way around the edges of seventh-grade mixers hoping to be noticed.

If only Debbie Laney had read the script I’d written for her.

“Hey Sue, look, it’s Lonely Guy. Walking alone down the street, threadbare collar turned up to the cold November wind. Suddenly I feel so shallow.”

My fantasies were becoming self-conscious and were harder to sustain. Still, I never had the courage to just talk to Debbie Laney – until the day I was beat up. On that day, I was riding my bike to the Y across a footbridge on a golf course where three “hoods” blocked my way. When I asked them to move, they blocked the footbridge completely.

I said, “Don’t be such pricks.”

* * *

With one slow-motion roundhouse kick, I ruin the lives of three…

* * *

POW! Right after I said “pricks,” one of the hoods hit me hard in the face, I fell off my bike and began to bleed. The hoods rode off laughing and I lay there measuring my options. Since I couldn’t go into the Y with blood all over my face and shirt, there was

clearly

only one alternative – let the blood dry on my face and then pedal to Debbie Laney’s house. When I got there, I would park my cool Sting Ray bike with Banana Seat and Ram’s Horn handlebars, ring the doorbell, and give ‘er an eye-full of the rough-and-tumble life we Lonely Guys lead. I wouldn’t even mention the injury unless she brought it up.

“There’s what? Blood, you say?”

Twenty minutes later, the look in Mrs. Laney’s eyes when she opened her door suggested my fantasy wasn’t playing out as scripted and the soundtrack of

Taxman

came to a scratching halt. Debbie wasn’t home and never saw Lonely Bloody Guy. Mrs. Laney did, but just cleaned me up and sent me home. As I prepped my cool Sting Ray bike with Banana Seat and Ram’s Horn handlebars for flight, I looked back at Mrs. Laney and said, “But you’ll tell Debbie about, …

you

know. Okay?”

Back at the Millstone, the six of us dealt with Dad’s death privately, each of us retreating to our rooms – to play a guitar, to build a model plane, to draw comic book super-heroes. With Dad no longer our common enemy, fights between the four little ones became worse.

Chris’s diary, August 26, 1966

Dan and Luke have been fighting so much. There are, on the average, 3 free-for-alls a day. Both demand full rights. Luke’s a Goddamn needle and Dan’s a Bull. Luke is worse even than Collin. He smokes. He spends all his time in the basement. He has big plans for his stupid comic book career. He likes his hamsters more than anyone

.

When Dad was alive, at least we all knew what was wrong with us. Now the house seemed to be unraveling and we weren’t sure why. With Kip back at college studying pre-law, Jeff and the remaining Pagans limped along through the fall and finally disbanded. Everything was just different. There was no Kip, no Pagans, no Dad; even the Millstone was up for sale. The dark star we’d revolved around so long was gone and we became aware of a big bad world beyond the gates of the Millstone and saw things were just as shitty out there.

Barely a month after Dad died, Kip noted in his diary: “Sniper in Texas killed 12 people, wounded 33. They said he was an Eagle Scout and worked at a bank … like me.” This was the summer Richard Speck raped and strangled eight nurses in Chicago and Capote’s

In Cold Blood

was a best seller. Even my Beatles were in trouble, with John’s controversial statement, “We’re more popular than Christ.” We saw these things on TV and on the cover of Mom’s

Life

magazines and felt our frying pan give way to fire. We wondered if our troubled childhoods were just the cartoon before the movie.

Troop strength in Viet Nam leapt to nearly half a million in ’66 and the military draft was sweeping through neighborhoods. Without Dad around to dominate the political conversation, Mom’s liberal views flowered; books like

The Anti-Communist Impulse

and authors like Noam Chomsky became dinnertime conversation. When Jeff’s reading convinced him that joining the Navy meant he had to “barbecue farmers,” Mom used connections at the Mayo Clinic to get him a psychiatric

deferment; when he entered college he began studying medicine.

Chris, too, could see revolution was in the air and discovered he had a lot more to be mad about than just three little brothers. With the war, civil rights, and women’s liberation on the

Huntley-Brinkley Report

every night, he could now smolder over a different injustice every day and not repeat one for weeks. His anger and emotion on occasion surprised even him.

Brother Chris, today

I didn’t understand what happened to me in Mr. Mason’s history class in September of that year. One day he rolled the projector into the room and played a pulp anti-communist film, something that looked like it was written by the Pentagon. When the lights went back on, I raised my hand and said the film was propaganda and its use in a public school was inappropriate. He scolded me in front of the class, said I didn’t know what I was talking about and that I wasn’t entitled to make judgments about his pedagogy.

The next day I retaliated. I remained totally silent and sat sideways in my chair staring out the window at the Mayo High School parking lot.

At the end of class, he asked me to stay behind. He was friendly and conciliatory, saying he wanted me to continue participating in class and that he didn’t mean to jump on me the way he did.

I have no idea how much he knew about me personally. Dad’s death had been mentioned in the newspaper a few weeks before and so he may have known I was raw. In any event, his kindness gave me permission to feel my sorrow. Mr. Mason felt soft to me; warm and human. I may have seen in him the father I needed. Here was a big, friendly, centered, sober and non-screwed-up man; and he was concerned about me.

He probably thought he was just patching things up with one of his students, but what he got for his efforts was a flood of tears.

In the empty classroom, I collapsed and just came apart completely. I remember weeping so hard my diaphragm and ribs hurt. He let me have my cry without shaming or limiting me and then gave me a pass to go to the bathroom to pull myself together before my next class. Years later I could see the tears of that day were part of a deep pain that had started a long, long time ago.