Thinking, Fast and Slow (43 page)

Read Thinking, Fast and Slow Online

Authors: Daniel Kahneman

The term

utility

has had two distinct meanings in its long history. Jeremy Bentham opened his

Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation

with the famous sentence “Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters,

pain

and

pleasure

. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do.” In an awkward footnote, Bentham apologized for applying the word

utility

to these experiences, saying that he had been unable to find a better word. To distinguish Bentham’s interpretation of the term, I will call it

experienced utility

.

For the last 100 years, economists have used the same word to mean something else. As economists and decision theorists apply the term, it means “wantability”—and I have called it

decision utility

. Expected utility theory, for example, is entirely about the rules of rationality that should govern decision utilities; it has nothing at all to say about hedonic experiences. Of course, the two concepts of utility will coincide if people want what they will enjoy, and enjoy what they chose for themselves—and this assumption of coincidence is implicit in the general idea that economic agents are rational. Rational agents are expected to know their tastes, both present and future, and they are supposed to make good decisions that will maximize these interests.

Experienced Utility

My fascination with the possible discrepancies between experienced utility and decision utility goes back a long way. While Amos and I were still working on prospect theory, I formulated a puzzle, which went like this: imagine an individual who receives one painful injection every day. There is no adaptation; the pain is the same day to day. Will people attach the same value to reducing the number of planned injections from 20 to 18 as from 6 to 4? Is there any justification for a distinction?

I did not collect data, because the outcome was evident. You can verify for yourself that you would pay more to reduce the number of injections by a third (from 6 to 4) than by one tenth (from 20 to 18). The decision utility of avoiding two injections is higher in the first case than in the second, and everyone will pay more for the first reduction than for the second. But this difference is absurd. If the pain does not change from day to day, what could justify assigning different utilities to a reduction of the total amount of pain by two injections, depending on the number of previous injections? In the terms we would use today, the puzzle introduced the idea that experienced utility could be measured by the number of injections. It also suggested that, at least in some cases, experienced utility is the criterion by which a decision should be assessed. A decision maker who pays different amounts to achieve the same gain of experienced utility (or be spared the same loss) is making a mistake. You may find this observation obvious, but in decision theory the only basis for judging that a decision is wrong is inconsistency with other preferences. Amos and I discussed the problem but we did not pursue it. Many years later, I returned to it.

Experience and Memory

How can experienced utility be measured? How should we answer questions such as “How much pain did Helen suffer during the medical procedure?” or “How much enjoyment did she get from her 20 minutes on the beach?” T Jon e t8221; T Jhe British economist Francis Edgeworth speculated about this topic in the nineteenth century and proposed the idea of a “hedonimeter,” an imaginary instrument analogous to the devices used in weather-recording stations, which would measure the level of pleasure or pain that an individual experiences at any moment.

Experienced utility would vary, much as daily temperature or barometric pressure do, and the results would be plotted as a function of time. The answer to the question of how much pain or pleasure Helen experienced during her medical procedure or vacation would be the “area under the curve.” Time plays a critical role in Edgeworth’s conception. If Helen stays on the beach for 40 minutes instead of 20, and her enjoyment remains as intense, then the total experienced utility of that episode doubles, just as doubling the number of injections makes a course of injections twice as bad. This was Edgeworth’s theory, and we now have a precise understanding of the conditions under which his theory holds.

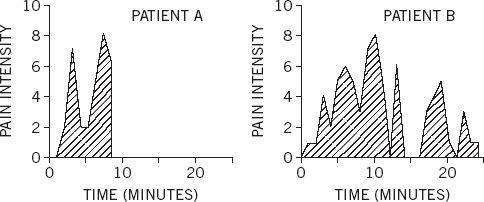

The graphs in figure 15 show profiles of the experiences of two patients undergoing a painful colonoscopy, drawn from a study that Don Redelmeier and I designed together. Redelmeier, a physician and researcher at the University of Toronto, carried it out in the early 1990s. This procedure is now routinely administered with an anesthetic as well as an amnesic drug, but these drugs were not as widespread when our data were collected. The patients were prompted every 60 seconds to indicate the level of pain they experienced at the moment. The data shown are on a scale where zero is “no pain at all” and 10 is “intolerable pain.” As you can see, the experience of each patient varied considerably during the procedure, which lasted 8 minutes for patient A and 24 minutes for patient B (the last reading of zero pain was recorded after the end of the procedure). A total of 154 patients participated in the experiment; the shortest procedure lasted 4 minutes, the longest 69 minutes.

Next, consider an easy question: Assuming that the two patients used the scale of pain similarly, which patient suffered more? No contest. There is general agreement that patient B had the worse time. Patient B spent at least as much time as patient A at any level of pain, and the “area under the curve” is clearly larger for B than for A. The key factor, of course, is that B’s procedure lasted much longer. I will call the measures based on reports of momentary pain hedonimeter totals.

Figure 15

When the procedure was over, all participants were asked to rate “the total amount of pain” they had experienced during the procedure. The wording was intended to encourage them to think of the integral of the pain they had reported, reproducing the hedonimeter totals. Surprisingly, the patients did nothing of the kind. The statistical analysis revealed two findings, which illustrate a pattern we have observed in other experiments:

- Peak-end rule: The global retrospective rating was well predicted by the average of the level of pain reported at the worst moment of the experience and at its end.

- Duration neglect: The duration of the procedure had no effect whatsoever on the ratings of total pain.

You can now apply these rules to the profiles of patients A and B. The worst rati Jon er soever on ng (8 on the 10-point scale) was the same for both patients, but the last rating before the end of the procedure was 7 for patient A and only 1 for patient B. The peak-end average was therefore 7.5 for patient A and only 4.5 for patient B. As expected, patient A retained a much worse memory of the episode than patient B. It was the bad luck of patient A that the procedure ended at a bad moment, leaving him with an unpleasant memory.

We now have an embarrassment of riches: two measures of experienced utility—the hedonimeter total and the retrospective assessment—that are systematically different. The hedonimeter totals are computed by an observer from an individual’s report of the experience of moments. We call these judgments duration-weighted, because the computation of the “area under the curve” assigns equal weights to all moments: two minutes of pain at level 9 is twice as bad as one minute at the same level of pain. However, the findings of this experiment and others show that the retrospective assessments are insensitive to duration and weight two singular moments, the peak and the end, much more than others. So which should matter? What should the physician do? The choice has implications for medical practice. We noted that:

- If the objective is to reduce patients’ memory of pain, lowering the peak intensity of pain could be more important than minimizing the duration of the procedure. By the same reasoning, gradual relief may be preferable to abrupt relief if patients retain a better memory when the pain at the end of the procedure is relatively mild.

- If the objective is to reduce the amount of pain actually experienced, conducting the procedure swiftly may be appropriate even if doing so increases the peak pain intensity and leaves patients with an awful memory.

Which of the two objectives did you find most compelling? I have not conducted a proper survey, but my impression is that a strong majority will come down in favor of reducing the memory of pain. I find it helpful to think of this dilemma as a conflict of interests between two selves (which do

not

correspond to the two familiar systems). The

experiencing self

is the one that answers the question: “Does it hurt now?” The

remembering self

is the one that answers the question: “How was it, on the whole?” Memories are all we get to keep from our experience of living, and the only perspective that we can adopt as we think about our lives is therefore that of the remembering self.

A comment I heard from a member of the audience after a lecture illustrates the difficulty of distinguishing memories from experiences. He told of listening raptly to a long symphony on a disc that was scratched near the end, producing a shocking sound, and he reported that the bad ending “ruined the whole experience.” But the experience was not actually ruined, only the memory of it. The experiencing self had had an experience that was almost entirely good, and the bad end could not undo it, because it had already happened. My questioner had assigned the entire episode a failing grade because it had ended very badly, but that grade effectively ignored 40 minutes of musical bliss. Does the actual experience count for nothing?

Confusing experience with the memory of it is a compelling cognitive illusion—and it is the substitution that makes us believe a past experience can be ruined. The experiencing self does not have a voice. The remembering self is sometimes wrong, but it is the one that keeps score and governs what we learn from living, and it is the one that makes decisions Jon thaperienci. What we learn from the past is to maximize the qualities of our future memories, not necessarily of our future experience. This is the tyranny of the remembering self.

Which Self Should Count?

To demonstrate the decision-making power of the remembering self, my colleagues and I designed an experiment, using a mild form of torture that I will call the cold-hand situation (its ugly technical name is cold-pressor). Participants are asked to hold their hand up to the wrist in painfully cold water until they are invited to remove it and are offered a warm towel. The subjects in our experiment used their free hand to control arrows on a keyboard to provide a continuous record of the pain they were enduring, a direct communication from their experiencing self. We chose a temperature that caused moderate but tolerable pain: the volunteer participants were of course free to remove their hand at any time, but none chose to do so.

Each participant endured two cold-hand episodes:

The short episode consisted of 60 seconds of immersion in water at 14° Celsius, which is experienced as painfully cold, but not intolerable. At the end of the 60 seconds, the experimenter instructed the participant to remove his hand from the water and offered a warm towel.

The long episode lasted 90 seconds. Its first 60 seconds were identical to the short episode. The experimenter said nothing at all at the end of the 60 seconds. Instead he opened a valve that allowed slightly warmer water to flow into the tub. During the additional 30 seconds, the temperature of the water rose by roughly 1°, just enough for most subjects to detect a slight decrease in the intensity of pain.

Our participants were told that they would have three cold-hand trials, but in fact they experienced only the short and the long episodes, each with a different hand. The trials were separated by seven minutes. Seven minutes after the second trial, the participants were given a choice about the third trial. They were told that one of their experiences would be repeated exactly, and were free to choose whether to repeat the experience they had had with their left hand or with their right hand. Of course, half the participants had the short trial with the left hand, half with the right; half had the short trial first, half began with the long, etc. This was a carefully controlled experiment.

The experiment was designed to create a conflict between the interests of the experiencing and the remembering selves, and also between experienced utility and decision utility. From the perspective of the experiencing self, the long trial was obviously worse. We expected the remembering self to have another opinion. The peak-end rule predicts a worse memory for the short than for the long trial, and duration neglect predicts that the difference between 90 seconds and 60 seconds of pain will be ignored. We therefore predicted that the participants would have a more favorable (or less unfavorable) memory of the long trial and choose to repeat it. They did. Fully 80% of the participants who reported that their pain diminished during the final phase of the longer episode opted to repeat it, thereby declaring themselves willing to suffer 30 seconds of needless pain in the anticipated third trial.