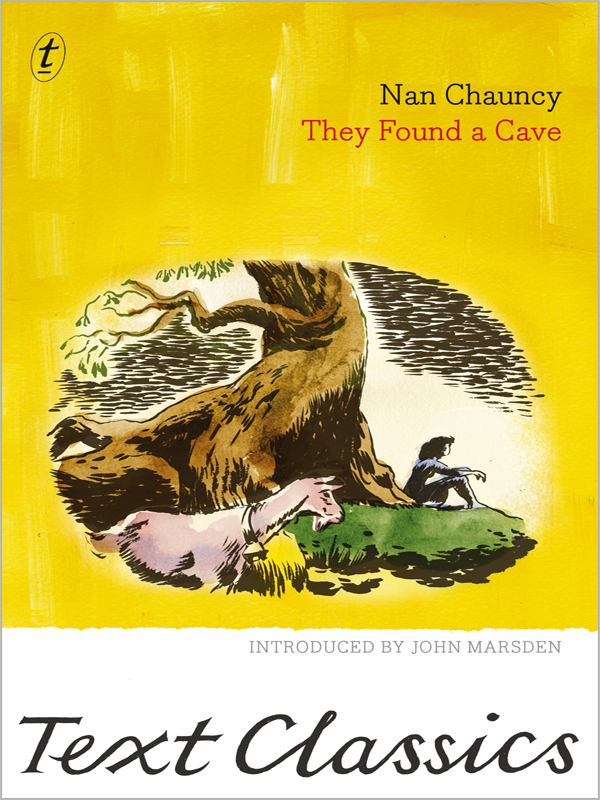

They Found a Cave

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

NAN CHAUNCY

was born Nancen Beryl Masterman in England in 1900. She moved with her family to Tasmania when she was twelve, to Bagdad, north of Hobart.

Nan grew up surrounded by the bush that would inspire her writing. Her love of the outdoors led to a lifelong association with the Australian Girl Guides. She returned to the UK in her early thirties and lived for a time on a houseboat on the Thames. She travelled in northern Europe and taught English at a Girl Guide school in Denmark.

On the voyage back to Australia in 1938 Nan met Helmut Anton Rosenfeld. They changed their name to Chauncy soon after marrying and lived in the family cottage at Bagdad, turning the property into a wildlife sanctuary, Chauncy Vale. Nan worked as a scriptwriter for the ABC and they had a daughter, Heather.

In 1947 Nan published her first novel,

They Found a Cave

, set in the hills around Bagdad. She published a further thirteen books, including

Tiger in the Bush

,

Devil's Hill

and

Tangara

, which were awarded CBCA Book of the Year in 1958, '59, and '61. Her works demonstrate her respect for the environment, and her fresh style marked the beginning of shift towards a greater realism in Australian children's novels.

Nan Chauncy was the first Australian writer to be awarded the Hans Christian Andersen Diploma of Merit, and the CBCA presents the biennial Nan Chauncy Award in her honour. She died at Chauncy Vale in 1970.

JOHN MARSDEN

is one of Australia's most-loved authors. He has written more than thirty books for children and young adults including the hugely popular

Tomorrow

series. His books have sold more than three million copies in Australia and have been published around the world. John Marsden is the founder/principal of Candlebark School in the Macedon Ranges in Victoria.

ALSO BY NAN CHAUNCY

World's End was Home

A Fortune for the Brave

Tiger in the Bush

Devil's Hill

Tangara

Half a World Away

The Roaring 40

High and Haunted Island

The Skewbald Pony

Panic at the Garage

Mathinna's People

Lizzie's Lights

The Lighthouse Keeper's Son

Â

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Nan Chauncy 1948

Introduction copyright © John Marsden 2013

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by Oxford University Press, London, 1948

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company 2013

Cover illustration by WH Chong after original illustrations by Margaret Horder

Cover design by WH Chong

Page design by Text

Typeset by Midland Typesetting

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press, an Accredited ISO AS/NZS 14001:2004

Environmental Management System printer

Primary print ISBN: 9781922147196

Ebook ISBN: 9781922148261

Author: Chauncy, Nan, 1900-1970 author.

Title: They found a cave / by Nan Chauncy; introduced by John Marsden.

Target Audience: For children.

Series: Text classics.

Subjects: ChildrenâTasmaniaâConduct of lifeâJuvenile fiction.

Country lifeâTasmaniaâJuvenile fiction.

CavesâTasmaniaâJuvenile fiction.

TasmaniaâJuvenile fiction.

Dewey Number: A823.3

Â

CONTENTS

Â

A Child's First Primer of Subversion

by John Marsden

Â

Â

WHEN I was nine years old and living in Tasmania, my infant sister had to spend some time in Royal Hobart Hospital. We visited her every day, but the crowd around her bedside was dense, and I found it hard to be noticed.

Bored, I turned to the bed next to her. Occupying it was a little boy, aged perhaps six or seven. Wan and listless, he lay there with no one to talk to. In those days visiting hours were enforced by stern nurses. For only one hour a day were visitors permitted near the children, so the isolation of this boy was very obvious.

I was quite obsessed with little toy cars, and I started playing with some of my cars on his bedspread, involving him in the stories I created. He seemed to enjoy this, but it wasn't for a week or so that one of the nurses told my mother his story.

He came from a remote settlement on the west coast of Tasmania, and no one in his family could afford the long trip to Hobart to visit him. He had been in the hospital for more than two months. I was rather gratified when the nurse told my mother that my visits had transformed him, and that all day long he lay in bed waiting eagerly for our game with the cars. It made me even more enthusiastic about playing with him, and I'm afraid that I neglected my sister completely.

That was 1959. Stories about the hardship and isolation experienced by families in bush communities were commonplace in Tasmania then, and no doubt in other states of Australia as well.

These were the people Nan Chauncy wrote about. The battlers, the hermits, the fringe dwellers, the nonentities. Many had hardly been to school; many were illiterate. Badge, the child-hero of Chauncy's book

Tiger in the Bush

has never seen canned food, never seen a camera, never seen electric light. When a visitor extends his hand, Badge stares at it, bewildered. No one has ever offered to shake his hand before, and he doesn't know what to do.

No one else in the post-war world wrote about these people. Perhaps no well-known Australian writer since Banjo Paterson or Henry Lawson had taken much interest in them. But Chauncy, the privately educated daughter of a professional family from Middlesex, England, who emigrated to Tasmania with her family when financial troubles beset them, somehow developed an admiration, a respect, and affection for them which permeated most of her books. She was clearly affected by the bonds which held their families together, and the loving relationships they often developed. An ardent conservationist long before it was fashionable, she recognised that these bush people loved, in an unsentimental way, the Tasmanian landscape and the native creatures which inhabited it.

People like Badge and his family were not educated in the conventional sense of the word, but Chauncy showed them to have an extensive knowledge of their environment, and outstanding bush skills.

In

They Found a Cave

, Chauncy's first novel, we are introduced to a family which seemingly mirrors Chauncy's ownâwell-educated immigrants from England. With names like Nigel, Brickenden and Anthony, the children seem like aliens in the rough-and-tumble world of the Tasmanian bush. Sent from England to stay with their aunt when the Second World War broke out, they expect that they will soon be going to boarding school, but in the meantime they flourish in the free atmosphere of farm life. We can imagine the young Nan Chauncy being equally exhilarated by the contrast between Tasmania and the well ordered world of Middlesex.

However the success of

They Found a Cave

rests not upon the shoulders of the young travellers who are adjusting to a very different lifestyle, but upon the remarkable Tasmanian boy aptly nicknamed Tas.

Tas personifies everything Chauncy admired about the uncivilised, unschooled, knowledgeable and enterprising Tasmanians with whom she must have mingled when the family moved to the quaintly named Bagdad, a tiny rural community north of Hobart. Tas has ânever had a chance' at formal education, but he has spirit, initiative, bush skills and farm skills. He is a born leader.

âIt seemed impossible to climb higher, but always Tas pointed out a wayâ¦'

Tas is marked out as special for another reason however. There is something quite extraordinary about him; an aspect of his life that is almost unknown in children's books prior to the publication of

They Found a Cave

. It is this: Tas has a mother and step-father who are simply awful. They are bullies, liars and thieves. They have no redeeming qualities. Not even Charles Dickens dared give his fictitious children such horrible parents. One has to skip ahead to Roald Dahl's

Matilda

to find parents equally repellent, but the Wormwoods are slapstick figures, whereas Chauncy's Pinners are credible in their viciousness.

And even more remarkably, Chauncy gives children, via

They Found a Cave

, tacit permission to leave such parents. Given that the book was written in a conservative eraâa time when middle-class parents had a shared understanding of the term âfamily values'âthe idea that children could and even should take the initiative to extricate themselves from damaging family environments and become responsible for their own care was truly revolutionary. We do not find this level of subversion in the works of that mass-market phenomenon of the 1940s and 50s, Enid Blyton. We do not find it in popular American titles such as the Nancy Drew mysteries or the Bobbsey Twins series. We do not find it in the distinguished Australian children's authors of the period, such as Joan Phipson, Colin Thiele, or Ivan Southall.

There is not a word of criticism of the children in

They Found a Cave

for going bush, for living rough, for defying adults, for walking out on the grownups who treat them badly.

Nigel even escapes from police custody without any negative consequences.

They Found a Cave

is not a cartoon or comic strip however. For all that Tas plots against his mother and stepfather, undermines their authority, and effectively âdivorces' himself from them, his sense of honour remains intact. When the police ask him for help as they prepare to prosecute Pa and Ma Pinner, Tas replies: âLook, Mr Bentley, I'm not giving evidence against Ma. Better leave me out of this.'

Given that it was published in 1948,

They Found a Cave

does contain a few anachronisms and at least one episode that causes twenty-first-century readers to cringe. The sale of the skeleton of an aboriginal Tasmanian to a âscientific party' makes for awful reading nowadays. It is at odds with Chauncy's great respect for Indigenous Tasmanians and her compassion for the suffering they endured at the hands of white settlers. But it is also social history: a reminder of the ignorance and thoughtlessness that were endemic in Australian society when Chauncy wrote her first novel.

That aside, what strikes the contemporary reader most about

They Found a Cave

is that it is remarkably modern. The pace is lively, the language accessible, the characters memorable, and the politics progressive. The respect for young people is palpable. Above all it is an entertaining story, âa good read'.

Filmmakers recognised its cinematic qualities, and in 1962 it was given a new lease of life when a film version was released. This was another remarkable achievement, as films adapted from Australian children's books of the period were few and far between.

With

They Found a Cave

Nan Chauncy launched one of Australia's most important literary careers, and redefined the tone and style of children's literature in this country.