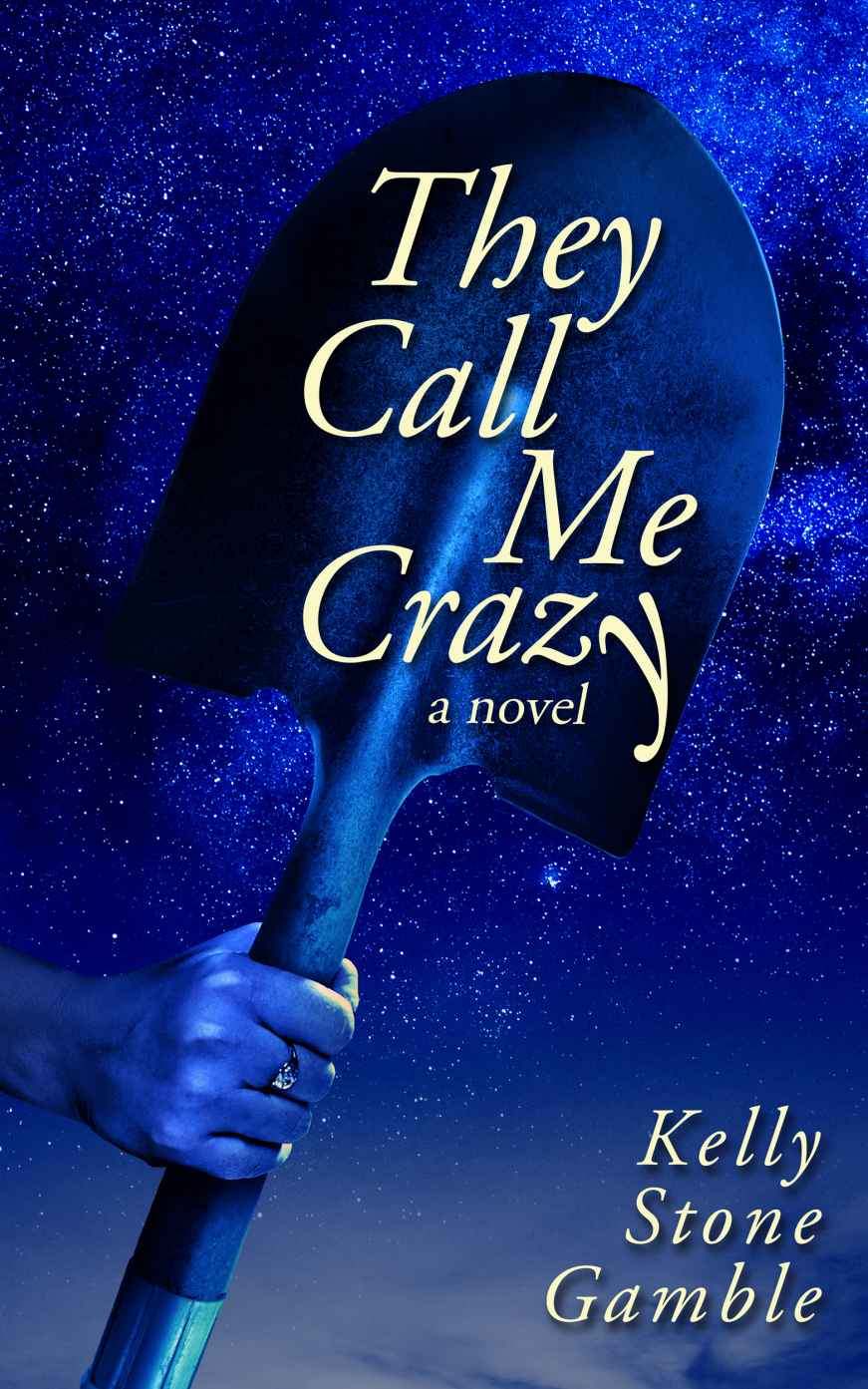

They Call Me Crazy

Read They Call Me Crazy Online

Authors: Kelly Stone Gamble

Table of Contents

They Call Me Crazy

Copyright © 2014 by Kelly Stone Gamble. All rights reserved.

First Kindle Edition: October 2014

Thank you for downloading this Red Adept Publishing eBook |

Join our mailing list and get our monthly newsletter filled with upcoming releases, sales, contests, and other information from Red Adept Publishing. |

|

|

Or visit us online to sign up at |

|

Red Adept Publishing, LLC

104 Bugenfield Court

Garner, NC 27529

http://RedAdeptPublishing.com/

Cover and Formatting:

Streetlight Graphics

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to locales, events, business establishments, or actual persons—living or dead—is entirely coincidental.

For my men: Joe, Dillon, Theron, Kerry, Anthony

Chapter One

Cass

T

here is nothing easy about burying your husband. From the moment he drops to the ground to that last shovelful of dirt, the entire process is weakening. I hate to simply say today was difficult. A day without a cigarette is difficult. Sending Roland to God’s acre was so much more than that.

Kneeling beside his grave, I pat the moist dirt one last time. “Sleep tight. Don’t let the bugs bite.” Grams used to say that to me when she put me to bed. The rhyme never seemed quite right until now.

I stand and stretch, leaning first to one side and then the other. I turn and face the river that runs behind our house, the boundary line that divides Kansas and Missouri. The two sides aren’t much different, if you ask me. The water looks inviting as I stand there covered with dirt mixed with sweat. I wish I knew how to swim.

I turn back to Roland’s grave and scream, “Who the hell moves their wife to the side of a river, knowing she can’t swim?”

He doesn’t answer, which is a good thing. I’m not in the mood to argue with him. He’s probably figured that out by now. I go to the water hose that Roland kept on the side of the house. It won’t wash everything away, but it’s a start.

As the cool water runs over me, I turn to our house, which is more like a small shack. Once I go inside, it will become

my

house. The two front windows are shaded with aluminum foil and duct tape. Chipped white paint over untreated slats adds to the trailer-trash effect. The foundation has been sliding over the years. I never noticed much, but today, it looks lopsided. I tilt my head.

Better.

I turn off the water and lay the hose on the ground, not bothering to wind it back up. As I walk onto the porch, the rotting wood planks yield under my feet. Two of the boards are missing; I know where to avoid stepping without even looking down. All it needs are a few new planks and a hammer. I can do that.

I open the front door, stand in the frame, and listen. From the kitchen, Roland’s clock—the watchful black cat whose eyes and tail move back and forth—ticks off the seconds, waiting for the big hand to hit twelve so it can expel a screeching

meow

. In the living room, the ceiling fan whirs noisily as a result of the accumulated dust and poor installation, yet the sound mixes almost harmonically with the beep, beep, beep of the answering machine. I turn off the fan and erase the messages without bothering to play them.

It takes six steps to cross the width of the living room. I pass through the doorway that leads to our bedroom—

my

bedroom. I have to get used to saying that. The bed is unmade, and dirty clothes are piled in one spot on the floor, the clean ones in another stack. They’ve been there so long that I’m not quite sure which is which. It doesn’t matter. Tomorrow, I will make new piles: his and mine. Things to keep. Things to get rid of.

I walk into the bathroom. A dingy shower curtain, the little yellow ducks faded with age, hangs in the doorway between there and the bedroom. I have to turn sideways to sit on the toilet or my knees will hit the rusty pipes under the sink. The only window is the one that I painted on the wall last year, complete with a frame of marching yellow ducks to match the shower-curtain door. The floorboard is gray with dust, and the small rug, in the few spots where it isn’t threadbare and worn to a dull slate color, is black. The tile grout around the bathtub is also black; I’ve been expecting a mushroom to grow out of it any day. The toilet has no lid.

Just an extra step

, Roland used to say. The entire room reeks of mildew mixed with urine. I flush the toilet and spray some Lysol. It will do for tonight.

I lean over the tub. The bath spigot screeches, expelling rust-colored water. When the water is almost clear, I cram a washcloth into the open drain, the plug gone long ago. I wish I had bubbles. Maybe tomorrow.

I undress, consider throwing my clothes into one of the piles in the bedroom, then change my mind. They get their own pile on the bathroom floor. I don’t ever intend to wear them again.

As I turn back to the bath, I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror. “Not so bad.” My voice sounds lower, scratchier than usual. I clear my throat a few times and try again. “Not bad at all.”

Much better.

My thirty-seven years have not been unkind to me. A week of sleep, a little makeup, some strawberry-blond Clairol, and I’ll look five years younger. I decide to pick that up when I get the bubbles.

The medicine cabinet doesn’t have a door, and pill bottles fill the shelves. I can hear Roland saying, “Take your pills. They keep you from doing crazy shit.” I pick up the bottles, one by one, and dump their contents into the toilet. The pink, white, and blue pills swell in the water. Chemical cotton candy. I don’t flush them, thinking maybe they’ll clean the brown stains in the bowl and do some good after all.

I lower my body into the bathtub, and immediately, a weight lifts from me. Starting at the bottom and working up, I scrub my feet hard and let out a long sigh as a tingle moves from my big toe all the way up my leg.

I hold the bottle of shampoo under my nose, close my eyes, and inhale the scent of fresh apples. Sweet, but not floral. Lord knows we have enough flowers out here. Roland planted things in the yard: trees, flowers, bushes. Before we moved from town, he dug up all the pretty plants and put them in pots so he could bring them out here. We may have a dump for a shack, but we have a yard that could make the cover of

Better Homes and Gardens

.

I always thought Roland’s gardening was just a nice hobby. Harmless. But one day I walked out on the porch and saw him stick a Mason jar in the ground. He covered it up and put a rose bush on top. I didn’t say anything, but later, after he went to play pool with the boys, I dug up that rose bush and unscrewed the lid from that jar. Five hundred dollars. I put the money back and never said a thing.

I got in the habit of digging up everything he planted. And every time, I found another Mason jar full of cash.

“Where did you get all that money, Roland?” I say to the sagging ceiling above the tub.

And why in hell would you bury it in the yard?

I would never have asked him that when he was alive. He wouldn’t have told me anyway. Maybe now that he’s gone, he’ll be easier to talk to.

With a soapy finger, I draw a flower on the wall and watch as it melts down the cracked linoleum. The smell of the apple-scented shampoo comforts me like a cup of hot cider on a cold winter night—not at all like the hard cider Roland usually reeked of.

My eyes burn, and I wipe the shampoo from them, but it makes matters worse. I blink several times and fight back the tears. I lie back in the tub, plunge my head completely underwater, and let it all wash away.

Using my toes, I pull the washcloth free. The silty water disappears down the drain, leaving a brown ring. I’ll get to that tomorrow. Tonight, I want to sit on my porch and watch the flowers grow: the two-hundred-dollar petunias, the three-hundred-dollar begonias, and that five-hundred-dollar rose bush.

Tomorrow, I will plant my own flowers in the plot I prepared today. Daisies, I think, would be appropriate.

First, I need a new shovel.

A sliver of light cuts through the aluminum foil on the window and pulls me from sleep.

“Roland?” I roll over and touch the other side of the bed out of habit. Lately, his side has been empty more times than not. I guess from now on that’s almost a certainty.

After my bath yesterday, I sat on the porch until the moon shone high in the sky. I was exhausted but still felt a sense of renewal. People say after someone runs a mile, she’s stronger. I was stronger. I had run my mile. Uphill. If I count the past five years, I just finished a marathon. A part of me thought Roland would be there, too, to scold me or maybe just to laugh at me. But he didn’t come. He will—I’m sure of that—but he didn’t last night.

I do understand what I’ve done. Even when you live in a world that’s usually a bit foggy, you still see things. It’s hard to ignore the fact that you’ve hit a deer, even if there’s a heavy film covering your windshield—a thick, dirty film. The last flash of surprise on the deer’s face when he realizes he’s about to be roadkill, that’s the look Roland had. I left his eyes open.

Now, untangling my legs from the sheets, I sit on the side of the bed, pressing my feet against the cold wood floor. I’ve gotten a lot of splinters from walking around this broken-down shack barefoot. But that cold feeling on the soles of my feet in the mornings reminds me that I’m alive. Some days, that’s okay with me. Today, I’m not sure. At least Roland won’t be making fun of me anymore for having to dig wood chips out of my toes with a straight pin. I don’t think he’ll be making fun about much of anything.

I consider the piles of clothes on the floor. “And I’ll wear whatever I want today,” I say to the ceiling.

I know he can hear me. I smile because I also know he can’t answer.

Roland wasn’t all bad. In some marriages, he would probably be considered okay. He never hit me all that hard. He preferred to pop me on top of the head once in a while as opposed to using any real physical force. Maybe he didn’t want to leave bruises. I’m sure he cheated on me. None of his bimbos ever showed up on the Hill, so at least he kept them under control. I guess that’s something. And he did stay with me even after we found out that I couldn’t have any kids. Not a lot of guys would do that; at least, that’s what he used to tell me.

But just because something isn’t bad doesn’t mean it’s good. And if the opportunity presents itself to make your life better, shouldn’t you take it? That’s what Lola would say, and my big sister has done okay singing that song.

“One day, Cass, it’s just going to happen, you know?” When we were younger, Roland would say this with a big smile, usually picking me up so I could wrap my legs around his waist. “One day,” he’d say, “everything is going to fall into place, like winning the lottery.”

He quit saying that when we moved out of the Deacon city limits. Maybe things did fall into place, and I missed it. Or maybe he quit buying scratch-offs.

But for the first thirteen years of our marriage, he was perfect, at least in my eyes. But in the last five years, I discovered that he could be bad, and when he was, he was a real pain in the ass, even about little stuff.

Last week, he told me to clean the barn, then after I did it, he complained about where I put things. “Why is my toolbox against the back wall? What if I need something real quick like?”

I couldn’t imagine needing an emergency screwdriver, but he seemed to think there might be such an occasion. “Because it’s big and gets in the way. Besides, you got so much junk, where the hell am I supposed to put everything?”

“Don’t be a dumbass, Cass. Cleaning a barn don’t take much brains. Even you can do it.” He held my arm tight enough to leave a bruise, while he started pointing with his free hand. “The toolbox goes there, the canoe next to the window. The lanterns over here.” He dropped my arm. “Forget it. I’ll do it myself. I don’t know why I keep you around.” Then he got in his truck and drove off.

I shrug the memory off and pick up a ratty plaid shirt that might be clean and a pair of Daisy Dukes that Roland would never have let me wear to town. My head hurts, and I shake it until I’m dizzy. The medicine cabinet is empty, and knowing that makes me smile.

I squint at the ceiling, imagining Roland looking down on me, and can’t help but stick out my tongue. Why did I keep

you

around?