There Must Be Murder (14 page)

Read There Must Be Murder Online

Authors: Margaret C. Sullivan

Tags: #jane austen, #northanger abbey, #austen sequel, #girlebooks

“Surely Lady Beauclerk has since regretted the

argument with General Tilney, if she felt true affection for

him?”

“Oh, no; Mr. Hornebolt dotes on her ladyship,

and on that cat, too. Says Lady J. is a superior creature of her

kind, and that his dear Agatha can spend just what she likes on her

bits of muslin, and any jumped-up half-pay officer who won’t stand

the expense of his wife’s fitting-out should be run through with

his own sword. I dare say he was talking about the general. But he

won’t stand for Lady Beauclerk keeping her title. He’s an

old-fashioned man, his mother was Mrs. Hornebolt and his wife will

be Mrs. Hornebolt. Miss don’t let her forget it, either; she will

have precedence over her own mother when she is Lady Beauclerk and

her mamma is Mrs. Hornebolt.”

She stopped for breath, and Matthew regarded her

with admiration. “My dear Miss Biddy, have you been listening at

doors again?”

“Of course! How else could I learn anything? You

like to listen to my gossip well enough, I’m sure. I’ll wager you

carry it back to your master right smart, too.”

The sudden, simple truth of her words shamed

Matthew; so much so, that when they reached Laura-place, he allowed

her to draw him into a dark niche by the kitchen door “to say

good-bye proper-like” with very good grace, and gave her a good-bye

kiss that left her dreamy-eyed and giggling.

***

The previous Sunday walk to Beechen Cliff had

been so successful that the Tilneys and the Whitings determined to

repeat it. The day was fine and sunny, and while the walk beside

the river was not as crowded as the Royal Crescent, they were not

alone, so MacGuffin remained on his lead. Henry and Eleanor both

were in fine spirits, having had good news from Matthew about their

father.

“I cannot help feeling a little sorry for

General Tilney,” said Catherine. “What if Lady Beauclerk had made

him very much in love with her?”

“I think he was, after his own fashion,” said

Henry. “But your amiable habit of putting yourself in another’s

place, and attributing to them your own unhappiness in such a

situation, has misled you, I fear. If my father is unhappy over

Lady Beauclerk, his disposition is such that it will not be of long

duration. He will soon tease himself out of it by recalling her

account at her mantua-maker’s, and congratulating himself on

escaping having to pay it.”

“Not to mention escaping having to walk her

cat,” said his lordship.

A man was pacing along the riverbank ahead of

them, near the spot where MacGuffin had waded out to chase the

ducks. As they approached him, Catherine recognized him. “That is

Mr. Shaw. Poor man! I do feel very sorry for him, and I dare say he

feels his misfortune more than General Tilney.”

The man bent over and picked up some objects

along the shoreline and placed them in his coat pockets. He paced

some more, and then, as they approached from one side and a large

family party from the other, he suddenly waded out into the

river.

Understanding dawned on Catherine. “Oh! He has

placed rocks in his pockets! Henry, Mr. Shaw means to drown

himself! You must stop him!”

“Shaw!” cried Henry. “I say, Shaw!”

Mr. Shaw whirled around and pointed a finger

accusingly at them. “Do not try to stop me! No one would help me,

no one would make my angel listen to me! It is too late! My blood

is on your hands!” He turned away and stumbled forward, walking

with odd high steps rather than wading. “She will know!” he cried,

pointing in the general direction of the Pulteney Bridge. “She will

know how much I loved her when she finds me floating by her very

door, and then she will regret her treatment of me! But it will be

too late! I shall be gone from this earth forever!”

Catherine, frightened beyond understanding,

cried, “Oh, stop him! Someone stop him!”

Henry released her arm and strode down the

riverbank. “That river must be freezing at this season, Shaw, and

you are frightening the ladies. Do come out now, there’s a good

fellow.” MacGuffin added several barks as emphasis as he strained

on his lead.

Mr. Shaw took two more thrashing steps into the

river, which flowed against him and broke around his knees. “I have

nothing to live for,” he said. “Nothing. My angel has forsaken me.

The devil must take me for his own now!”

Henry gave a short sigh of impatience, and then

bent down and took off MacGuffin’s lead. The dog immediately raced

for the river and plunged in.

Mr. Shaw flailed away from MacGuffin. “Begone,

hellbeast! Leave me to your dark master!” One of his feet slipped,

and he went down on one knee, struggling to keep his head above

water. Even in her fright, Catherine thought his behavior odd; he

said he wanted to drown himself, but seemed afraid to go under

water.

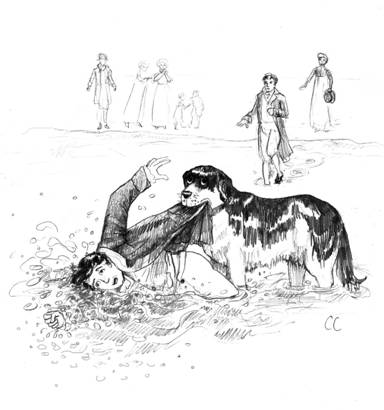

MacGuffin, up to his haunches in the water,

seized the floating end of Mr. Shaw’s tailcoat firmly in his mouth

and braced himself on the river bottom. Mr. Shaw tried to move away

from him, but MacGuffin held firm.

“He has been trained in water retrieval,” Henry

called to Mr. Shaw. “Trained very well, I may add. You might as

well give it up now.”

Mr. Shaw attempted to unbutton his coat and slip

out of it, but MacGuffin growled, the coat-tail still in his mouth,

and shook his head violently from side to side, as though playing a

game of keep-away. Mr. Shaw stopped struggling and began to weep

with loud braying sobs; he then buried his face in his hands.

Henry watched him for a long moment. “Do you

think you are the only man whose peace has been destroyed by Judith

Beauclerk?” he asked, his voice full of compassion. Mr. Shaw’s

turned to look at him; Henry gazed back at him steadily, and they

seemed to communicate something, a shared knowledge that made

Catherine suddenly uneasy.

MacGuffin tugged again, and at last Mr. Shaw

came with him, stumbling out of the river, the dog herding him like

a lost sheep and never letting go of the coat-tail until his

captive was safely on land and wrapped in a blanket produced by the

family party, which had watched the proceedings with fascinated

horror. A few more spectators had collected, including several

small boys who heard that someone had drowned himself and demanded,

in high-pitched, strident voices, to see the corpse. Lord Whiting

sent them away and consulted with the father of the family-party,

and they went to fetch his carriage, which was waiting in

Argyle-street.

Henry put an arm around Mr. Shaw’s shoulders,

still bowed in sorrow. He looked up at Catherine consciously, and

she turned and said to the fascinated onlookers, “Step away,

please; leave him be.” They turned, one by one, and drifted away,

as Henry spoke to Mr. Shaw in unintelligible tones.

The mother of the family-party would not be

moved so easily. “What is he saying?” she asked Catherine, peering

over her shoulder at Henry and Mr. Shaw huddled on the riverbank.

“What is he doing?”

“My husband is a priest,” said Catherine firmly.

“He will say all that is necessary.”

The woman’s face cleared. “Oh, a priest,” she

said. “Aye, he’ll take care of the poor devil.” She turned to shoo

her children away.

Lord Whiting and the father returned, and the

three men helped Mr. Shaw to get up and moving towards the bridge.

“Cat, take MacGuffin, and go to our lodgings with Eleanor,” Henry

called to her. “We will meet you there.”

***

Henry and John returned to Pulteney-street a few

hours later, and assured the worried ladies that they had returned

Mr. Shaw to his rooms in Westgate Buildings, saw him into dry

clothes and left him in front of a blazing fire.

“How could you leave him?” cried Catherine. “How

do you know he will not try again to destroy himself?”

“He did not really want to destroy himself,”

said his lordship, flinging himself into a chair. “He only wanted

someone to share his misery. Did you not see that he feared the

water? Only a man still in love with life would have such

fear.”

“And pray note that he chose to make his attempt

nearly on the Beauclerks’ doorstep,” said Henry. “He raved a bit in

the carriage about Judith finding him floating in the river and

being sorry she had cast him off, but it soon came out that he

really did not wish to drown himself; he had a wild scheme of

someone running for Judith so she could stop him from drowning

himself and reconcile with him.”

“He also waited until he was sure he had an

audience,” said Lord Whiting. “He could have jumped in before we or

that nice fellow from Hampshire got there, but he waited for us to

be close enough to see his act. I give him credit; ’twas as good as

anything one sees on Drury Lane. Though the poor fellow has had a

bad time of it.”

Henry looked at Catherine, who sat with her head

down, and her hands fastened in her lap; an attitude he knew to

mean that she was in some distress that she did not care to

vocalize. “Do not worry, my sweet. Mr. Shaw and I had a good talk,

and I made him see the foolishness of martyring himself to Miss

Beauclerk. I think he might even be on the way to mending his

broken heart.”

Catherine lifted her head and looked into

Henry’s eyes. “You once said to me that Miss Beauclerk had not

injured you; but the way you spoke to him today—the way you said he

was not the first man to have his peace destroyed by her—”

Henry and Eleanor exchanged glances, and Eleanor

said, “Catherine and John are part of our family now, Henry; I

believe you should tell them.”

He nodded, and said to Catherine, “I told you

the truth. Judith Beauclerk did not break my heart or injure me by

her flirtations. I regret I cannot say the same for my

brother.”

“Captain Tilney?”

“Yes. He came home several years ago, a newly

commissioned lieutenant in the Twelfth Light Dragoons, and fell for

Judith with all the ardent affection of a young man fresh from a

battlefield, and offered her his hand and his heart. She said that

she could not marry a mere Lieutenant Tilney, and he had to put

himself in the way of a battlefield commission or, better yet, a

knighthood so she could be Lady Tilney. Frederick told no one of

this, not even my father; and he went off to Toulon and put himself

in grave danger during the siege there, in a hopeless cause, trying

to cover himself with glory for her sake.”

“He won his commission?”

“Yes; he was Captain Tilney, but it was not

enough for Judith; he was not Sir Frederick. He presented himself

to Judith, and she laughed at him, and said she had never intended

to marry him or any officer, and how could he take her so

seriously? My brother changed that day, Cat; he changed from a

brave, headstrong, sometimes vain and thoughtless young man into

someone capable of amusing himself at the expense of another’s

comfort. He learned to give what he received from Miss Beauclerk;

and since then has found no woman worthy of his affection.”

Catherine considered this gravely. “That is why

he acted the way he did with Isabella Thorpe, I dare say; he knew

her for a vain coquette, and took his revenge on her.”

“Not so much revenge, I think, as recognizing

that Miss Thorpe’s was not a heart worth winning, or worth more

than a common flirtation, and perhaps taking advantage of it.”

“And now I understand why you did not wish Miss

Beauclerk to live at Northanger; if Captain Tilney came to visit, I

dare say it would be most uncomfortable for him.”

“Yes,” said Eleanor. “And my father promoted the

match between Frederick and Judith, which really was most eligible,

so Henry and I were astonished that he seemed to have forgotten the

outcome of it.”

“I do not understand why Miss Beauclerk would

refuse Captain Tilney and accept Sir Philip,” said Catherine.

“Captain Tilney will have a much larger estate and fortune.”

“I believe she always meant to get Beauclerk, if

she could,” said Henry. “She could not capture him with her own

charms, but her father made it possible with the terms of his

will.”

“So ambition makes fools of us all,” said his

lordship. “Eleanor, love, is that tea hot? I could use a cup.”

***

The fire in their bedroom was past its first and

highest blaze, and Henry and Catherine burrowed into their thick

quilts, embraced by the circle of light thrown off by Henry’s

candle as he read aloud the last chapter of

The Mysteries of

Udolpho

.

O! how joyful it is to tell of happiness,

such as that of Valancourt and Emily; to relate, that, after

suffering under the oppression of the vicious and the disdain of

the weak, they were, at length, restored to each other—to the

beloved landscapes of their native country,—to the securest

felicity of this life, that of aspiring to moral and labouring for

intellectual improvement—to the pleasures of enlightened society,

and to the exercise of the benevolence, which had always animated

their hearts; while the bowers of La Vallee became, once more, the

retreat of goodness, wisdom and domestic blessedness!