There is No Alternative (14 page)

Read There is No Alternative Online

Authors: Claire Berlinski

Fade to black.

She did not rehearse this speech; there was no speechwriter or teleprompter; it was live and impromptu. The performance is a miracle of menace, rhythm, dramatic timing. It is impossible to watch without thinking that you would not trade places with the miserable Mr. Frost for all the world.

I now take the train from London to Oxford, where I have an appointment to speak with the Master of Balliol College, Andrew Graham, about his memories of Margaret Thatcher. The Master is a man of the Left. From 1966 to 1969, he was an influential economic advisor to Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson; he worked again for Wilson between 1974 and 1976 at the policy unit attached to 10 Downing Street. In the early 1990s, he advised the leader of the Labour Party, John Smith. After Smith's death, he fell out spectacularly with the New Labourites:

You

may all be Thatcherites now, he told them, but count

me

out.

You

may all be Thatcherites now, he told them, but count

me

out.

I am seeing him because I want the other side of the story. I have met a series of Thatcher's cabinet ministers and her most ardent defenders. Now I want to hear the best and most serious case

against

Thatcher's economic policies (which we will not get from New Labour, because they are all Thatcherites now). He will not disappoint, but we will come back to that later.

against

Thatcher's economic policies (which we will not get from New Labour, because they are all Thatcherites now). He will not disappoint, but we will come back to that later.

I am early for my appointment, so I stroll slowly through the streets of Oxford. Oxford is two cities, sharply divided. The poets ignore the outskirts of the cityâthe menacing townie pubs with their tattooed patrons, places students know better than to enter, the seedy bedsits over the Cowley Road where the stairwells smell of urine and turmeric, the rows of kebab vans, all named

Ali's

, parked outside those stairwells and reeking of ancient mutton. The poets write about the city centerâa rook-racked, river-rounded city of dreaming spires, they call it, and they are right.

Ali's

, parked outside those stairwells and reeking of ancient mutton. The poets write about the city centerâa rook-racked, river-rounded city of dreaming spires, they call it, and they are right.

The Master of Balliol was my economics tutor when I was an undergraduate, many years ago. I had last seen him when I was in my early twenties. I was very fond of himâhe was warm, lively, unstuffy, a wonderful teacher. I had feared as I walked to our meeting that I would find him much older and that this would remind me that I too am much older, but to my delight he is unchanged.

He's running a few minutes late. He darts through the sitting room in the Master's lodge, spots me, beams broadly in welcome, then dashes up the staircase. “I'll just be another minute, Claire. I'm sitting for my portrait!” How lively and spry he looks, I think! Could it be that in the portrait he is stooped and wrinkled?

When he returns he escorts me to his office, with its high ceilings and heavy brocaded curtains framing a picture window overlooking Broad Street. Haphazard stacks of papers cover the floor, the tables, the chairs. We chat for a while about economics, then we turn to the subject of Thatcher's political presence. We are trying to put our finger on what it was about her that kept the electorate coming back for more and more and more, despiteâin his view, of courseâher disastrously misguided policies. What was the source of her charisma, I wonder aloud?

“Well,” he says, “I didn't think this, I never felt it, butâquite a lot of people, some menâfound her quiteâ

sexy

!”

sexy

!”

“Mmmm,” I say. “I've heard this. Who was it, Mitterrand, who called her Brigitte Bardot with Caligula's eyes?”

“Exactly! And I think some of it was the sex that goes with power, and I, you know, I just can't get on that wavelength. I won't say I don't find power interesting, I do, but I just can't get there with Mrs. Thatcher

at all

, I can't even get to square one! But I've heard it from people I was surprised by.”

at all

, I can't even get to square one! But I've heard it from people I was surprised by.”

“Perhaps you'd care to say who?”

He won't name names. “I mean, a colleague of mine in Balliol, who is now dead, was a professor of physics, went along to a seminar in All Souls, incredibly impressed by her, just sort of swept off his feet by how articulate and how clear she was, and by her general demeanor umâthis, she hadâ

I

wouldn't say, because

I

never

felt itâshe had, somewhere in thereâthere is something more interesting than just a domineering personality. There is a degree of magnetism that somehow all big leaders have. I didn't see it, couldn't

remotely

â”

I

wouldn't say, because

I

never

felt itâshe had, somewhere in thereâthere is something more interesting than just a domineering personality. There is a degree of magnetism that somehow all big leaders have. I didn't see it, couldn't

remotely

â”

Â

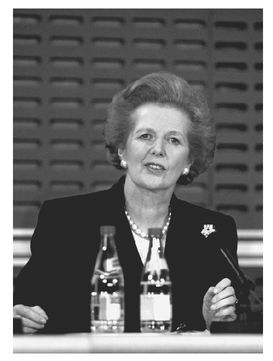

Thatcher addressing a conference on foreign policy in London, in 1989. “It was as if there was a sort of electric glow about her,” recalls the conservative MP David Ames. “She seemed to overshadow everyone.” Graham Wiltshire, who took this photograph, remembered that “the effect she had on these events was almost hypnotic.”

(Courtesy of Graham Wiltshire)

(Courtesy of Graham Wiltshire)

I get it, I get it. He wasn't attracted to Margaret Thatcher, no how, no way. I do note that it wasn't

me

who suggested he might be. “

I've

seen it,” I say. “And I'm still trying to figure out how to describe what it was that I seeâI mean, sex appeal is one aspect of it, but it's not just that, it'sâit is an

utter

confidence which is unbelievably rare in women.”

me

who suggested he might be. “

I've

seen it,” I say. “And I'm still trying to figure out how to describe what it was that I seeâI mean, sex appeal is one aspect of it, but it's not just that, it'sâit is an

utter

confidence which is unbelievably rare in women.”

“Yeah, I mean, going back to whatâI meanâI'm not a pacifist, I think war is sometimes essential, but I wasn'tâyou know, most people in the UK were sort of gung-ho about the Falklands War, I thought it was absolutely unnecessary, but I think she deserves enormous credit for that. I mean, one Exocet on one of those destroyers and the whole thing would have been a completely different story. Just a completely different story.”

In fact, the HMS

Sheffield

did take a direct hit from an Exocet missile. It was blasted apart. This did not for a moment cool the prime minister's ardor. But I agree with the point he is expressing. I have thought of it often, what it must have felt like to be her at that moment, of the enormous risks she took. The outcome was not at all guaranteed. “So,” the Master wonders aloud, “is that foolhardiness or is it courage?”

Sheffield

did take a direct hit from an Exocet missile. It was blasted apart. This did not for a moment cool the prime minister's ardor. But I agree with the point he is expressing. I have thought of it often, what it must have felt like to be her at that moment, of the enormous risks she took. The outcome was not at all guaranteed. “So,” the Master wonders aloud, “is that foolhardiness or is it courage?”

“In terms of psychological typing,” I say, “probably it would be described as a touch of narcissismâ”

“Yeah, yeah,” he agrees, nodding.

“And perhaps a bit of hypomania, as wellâ”

“Yeah, butâ” He pauses. “It's also a kind of guts.”

Armchair diagnosis can be taken only so far, but the words “narcissism” and “hypomania”âand “guts,” for that matterâdo fit her uncannily well. Take the Mayo Clinic's description of the narcissistic personality style, for example:

People who have a narcissistic personality style . . . are generally psychologically healthy, but may at times be arrogant, proud, shrewd, confident, self-centered and determined to be at the top. They do not, however, have an unrealistic image of their skills and worth and are not dependent on praise to sustain a healthy self-esteem. You may find these individuals unpleasant or overbearing in certain social, professional or interpersonal encounters . . .

58

58

Check, check, check. And hypomania? Without a doubt:

Some traits of hypomania: . . . filled with energy . . . flooded with ideas . . . driven, restless, and unable to keep still . . . often works on little sleep . . . feels brilliant, special, chosen, perhaps even destined to change the world . . . is a risk taker . . .

59

59

As for “guts,” I trust no definition is needed.

“I do think,” I say to the Master, “that men tend to be more certain in their convictions. This tends to be a male trait. Which is one reason why Thatcher is so unique.”

He nods. “Ah, she's interesting, yes.”

“I mean, you keep seeing comparisons of, say, Ségolène Royal with Thatcher, and that's absurd, they've got nothing at all in common, they're a completely different species. And the comparisons between Hillary Clinton and Thatcher seem to me not only from a policy point of view, but a personality point of view, completely ridiculous. Hillary conveys none of that absolute, rock-solid

authority

, which I think was the source of Thatcher's charismaâ”

authority

, which I think was the source of Thatcher's charismaâ”

“Yeah. Yeah.”

“Thatcher's wasn't a Bill Clinton kind of charisma at all.” I met Bill Clinton once at a reception held for him at Oxfordâhis alma materâduring the first years of his presidency. His charisma was just as it is always described. He shook my hand and did that thing for which he's famous: one hand holding mine, the other on my elbow, looking deeply into my eyes, and for one moment, just that moment, the clicking cameras stopped, the crowds faded to a blur, and I

knew

that the leader of the Free World was more interested in me, more interested in what I thought and felt, than anyoneâincluding my own motherâhad ever been before. His eyes told me clearly that if only this annoying Secret Service detail would stop hurrying him along, we would just talk and talk and talk, he and I; I would tell him about my thoughts about health care, and Social Security, and . . .

knew

that the leader of the Free World was more interested in me, more interested in what I thought and felt, than anyoneâincluding my own motherâhad ever been before. His eyes told me clearly that if only this annoying Secret Service detail would stop hurrying him along, we would just talk and talk and talk, he and I; I would tell him about my thoughts about health care, and Social Security, and . . .

“No. Not remotely,” agrees the Master.

“It's the charisma of someone who is absolutely certain she is rightâ”

“And with some of us, drives us completely

bonkers

, because we think she's so wrong!”

bonkers

, because we think she's so wrong!”

“I think that's the source of the passionate emotions about her,” I agree. Bernard Ingham attributes it to the sheer viciousness

of the Left, but the Master of Balliol is anything but a vicious man. Thatcher's brand of certainty was fascinating and maddening in equal measure, and if you happened to think her wrong, it was enough to make you

bonkers

. “So there's that utter certainty in herself,” I continue, “and there was something sexy about her, in a traditional way, especially as a young womanâshe was not a raving beauty, but she was attractiveâ”

of the Left, but the Master of Balliol is anything but a vicious man. Thatcher's brand of certainty was fascinating and maddening in equal measure, and if you happened to think her wrong, it was enough to make you

bonkers

. “So there's that utter certainty in herself,” I continue, “and there was something sexy about her, in a traditional way, especially as a young womanâshe was not a raving beauty, but she was attractiveâ”

“Yes, yes.”

“But also a maternal archetypeâshe reminded people of their mothers or their schoolteachersâ”

“Yeah, but, you know, I've never had that, you know, doesn't remotely work at all for me, not at all, so you'd have to findâbut you know, some people find that veryâ

attractive

!”

attractive

!”

Â

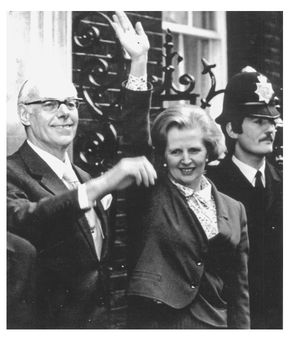

Margaret and Denis Thatcher stand outside No. 10 Downing Street directly after her 1979 election victory. Two days later, she arrived to address a meeting of Conservative backbench MPs. “She was flanked only by the all-male officers of the committee,” recalls Geoffrey Howe. “Suddenly she looked very beautifulâand very frail, as the half-dozen knights of the shires towered over her. It was a moving, almost feudal occasion. Tears came to my eyes . . . this overwhelmingly male gathering dedicated themselves enthusiastically to the service of this remarkable woman.”

(Courtesy of Graham Wiltshire)

(Courtesy of Graham Wiltshire)

Other books

The Midtown Murderer by David Carlisle

How We Lived (Entangled Embrace) by Erin Butler

My Lady Mage: A Warriors of the Mist Novel by Alexis Morgan

His Indecent Training 4 by Sky Corgan

The Epic of Gilgamesh by Anonymous

Beautiful Lies by Jessica Warman

rtbpdf by Cassie Alexandra

Pulse - Part Four (The Pulse Series) by Deborah Bladon

This Secret We're Keeping by Rebecca Done