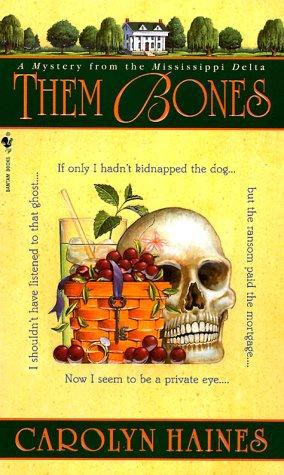

Them Bones

Authors: Carolyn Haines

1

Women in my family have a penchant for madness and mysterious "womb" disorders. It's never been clear to me whether one is the result of the other, or if both maladies are a curse upon the Delaney women for acts of desperation, usually associated with a man more deeply involved with either a bottle or a gun than a female.

But it was melancholy, not madness, that was on my mind as I stared at the empty driveway through the rain-pelted kitchen windows of Dahlia House. A misty veil had settled over the old plantation, shrouding the bare trunks of the leafless sycamore trees. This will be my last Thanksgiving on the fine, old estate. The tradition of Dahlia House is drawing to a close--I am the last of the Delaneys, a thirty-three-year-old, unwed, unemployed failure.

"Sarah Booth Delaney, get your skinny white ass away from that window, moonin' around like your great-aunt Elizabeth--and you know what happened to her."

Perhaps it

is

madness, because since my return to Zinnia,

Mississippi , the voice of my great-great-grandmother's nanny, Jitty, has become clear as a bell. I turned to confront her and blinked at the bell-bottoms and shiny polyester blouse that are part of her latest fashion trend--retro seventies. Though Jitty died in 1904 at a ripe old age, she has evoked some ghostly privilege and returned in her prime. In other words, hip-huggers look better on her than they would on me. It is only one of the things about her that annoy me.

"Leave me alone," I warned her as I went back to the stout oak table that had been in the Delaney family since Dahlia House was built in 1860. It, along with all of the other furnishings, will go on the auction block the week after Thanksgiving.

"You better quit this mopin' and find us a plan," Jitty said, taking a seat at the table, staring disapprovingly at the mess I had made. "In here in this cold kitchen making fruitcakes when the wolf is at the door. Where we supposed to go when they put us out of here? We're gone be living under the bridge, goin' through the

trash

of all your society friends for a bite to eat. You don't get busy, we're gone be in real trouble."

The cutting board glimmered with the jewels of chopped red and green cherries. I eyeballed the bottle of Jack Daniel's sitting on the table beside them. With sticky fingers I tipped the bottle into the fruitcake batter, and then lifted it to my lips.

"Don't tell me you taking after your great-uncle Lyle Crabtree." She glared at me through another fashion affectation, rose-tinted granny glasses. "Whiskey won't cure what ails you."

There was no point arguing with Jitty. I'd tried that, and I'd tried ignoring her. Nothing worked. I picked up the cutting board and dumped the bright cherries into the batter. "We always bake fruitcakes the week of Thanksgiving," I reminded her. "My life has been sacrificed on the altar of tradition, and I see no reason to quit now."

"In a week's time,

we'll

be homeless." Jitty pushed back her chair and stood, hands flat on the table for emphasis. "It's the responsibility of the Delaney family to provide for me. When you snatched my mama from the soil of

Africa , you took on an obligation that can't never be shirked. You belong to

me."

"I didn't snatch anyone from anywhere." This was old ground, and Jitty loved it. I was thoroughly sick of it.

"The sins of the father," she mumbled darkly.

My hands covered in the cherry-bejeweled batter, I picked up a knife and contemplated its sharp edge.

Jitty snorted. "No matter how I devil you, you can't hurt me with a knife. I'm already dead."

It was a well-taken point, but I wasn't defeated. I turned the blade to my chest. "What would happen to you if something happened to me?" I asked.

Her black currant eyes flickered. I finally had her. I was the last of the Delaneys. If I died, she'd have no one left to haunt.

Jitty sniffed. "Could be that I go wherever you go, for

eternity."

She jangled her annoying silver bangles. "Best thing for you to do is marry that banker man, have some kids, and pass me on to the next generation. It's tradition." She gave me a dark look. "Never been a Delaney woman couldn't catch her a man if she put her mind to it." Her bony finger pointed me up and down. "Look at yourself. You could be a knockout with that Delaney bone structure and your mama's figure, but you a mess, girl. Wearing your dead aunt's muumuu, no makeup and no foundation garments. And after all that time LouLane spent after your mama died, tryin' to teach you how to dress and behave. Wasted. Just wasted. No man wants a woman acts like a bag lady. You act like you've given up on yourself, like you can't tighten the rope on Harold Erkwell." She leaned closer. "Like maybe you're afraid to try."

Anger prevented a reply. The idea that Jitty would so willingly sacrifice me for financial security was infuriating. Especially to Harold Erkwell! But then, according to Jitty, sacrifice of the female was as much a Delaney tradition as tortured female organs.

"You're really pushing me. I--"

The solemn tones of the front doorbell caught me in mid-threat.

"It's one of your friends, one of the rich ones," Jitty said, fading slowly into the drab afternoon light. "What we need is a butler." Her voice echoed eerily in the kitchen. "Your grandma knew the value of a butler. That woman had class, which went a long way toward offsetting her female troubles. If she'd had more children than just your father, me

and

Dahlia House wouldn't be in this condition." She was gone.

Wiping my hands on a cloth, I went to the front door. I had no intention of opening it, but I was curious.

I heard my visitor beating against the old oak. She had tiny little fists, I deduced by the rat-a-tat sound.

"Sarah Booth Delaney, open up right this minute. I know you're in there." Staccato yipping punctuated the demand.

I closed my eyes. Tinkie Bellcase Richmond, one of Zinnia's most prominent "ladies," was at my door. She was accompanied by her six-ounce, pain-in-the-ass dog, Chablis. The mutt was so delicate that "if she fell off the sofa, she might break her legs." In Tinkie's book, that was a good quality. Tinkie's own moment of crowning glory was when the local doctor found her anemic and gave her prescription vitamins, an indicator that she was the type of woman who required high maintenance and special attention. I leaned against the door and hoped she'd go away.

"Sarah Booth, you can't hide from me." She pounded harder while the dust mop yapped at her feet.

I had no choice but to open the door. Avery Bellcase, Tinkie's father, was on the board of directors of the Bank of Zinnia. He might, at that very moment, be reviewing my last, desperate loan application. I didn't need Tinkie running home to tell him I'd been rude to her. At my level of society, being poverty-stricken was far more desirable than being rude.

I opened the door a crack. "Hi, Tinkie." The sun caught the salon highlights of Tinkie's perfect hairdo. "Hi, Chablis," I said to the dog, who was also glitzed.

"Are you going to ask us in?" Tinkie asked, disapproval on her perfectly made-up face.

"I've had the flu. I don't think you should expose yourself to my germs. I've been terribly sick." It was the only excuse that would explain my muumuu and bedraggled appearance, and appeal to Tinkie's view that illness was a sign of femininity.

Tinkie waved aside my concerns. "Madame Tomeeka just told me that a dark man from the past is coming back to Zinnia." She pushed through the door. "What am I going to do?"

Her face was bright with excitement. Obviously this dark man from the past was more exciting than her husband Oscar. A mummy would be more interesting than Oscar. But Oscar had wealth and power, two things in short supply at Dahlia House.

"I need a glass of sherry and a place to sit down." Tinkie fanned her face with her hand, though it was forty degrees in the open doorway and colder inside the house. I'd taken to heating only the kitchen and bath to save on the power bill.

"Tinkie," I said sweetly. "This isn't the time. I'm sick."

She looked at me, and for a moment her blue eyes registered confusion. "You need to go to the makeup counter at Dillard's and see if they can't find some base that will perk up your color. Maybe you should dye your hair." She lifted a limp strand. "Something auburn." One side of her mouth curled as she noticed a clot of fruitcake batter on my shoulder.

"I'm out of sherry," I informed her, hoping the lack of libations would move her back into the yard.

She walked into the parlor. The room was almost dark, what with the heavy curtains and the grim and rainy day. "If Oscar finds out, there'll be a killing." When she turned to face me, there were tears in her eyes. "You're the only woman I know who isn't driven by dark desires and erratic hormones. Tell me what to do about Ham!"

Tinkie was not referring to the staple of the Southern diet, and she was not going to go away. "I'll make us some coffee," I said on a sigh.

In the kitchen, I put the silver creamer and sugar bowl on the tray just as the coffeepot quit perking and Jitty decided to make another appearance.

"She'd pay good money for that ball of fur," Jitty said, nodding. "Cha-blis," she whispered. "What kind of person names a dog after a man in a book who dresses like a woman. Cha-blis."

"Go away," I said, knowing Jitty would ignore me. I admired the elegant design of the silver. It had been in the family for over a hundred years. Soon it would belong to someone else.

Jitty jangled her bracelets in my ear. "Tonight, when little Cha-blis goes out to take a whizz, you snatch her up and bring her home. Let a day or two pass, and you can reunite Cha-blis with her mistress and collect a reward."

"Get thee behind me, Satan." Jitty was fond of quoting the Bible when it served her purposes. I was proud of my rejoinder.

"What you think she'd pay for that dog? Maybe five hundred? Maybe a thousand? Especially if she got a ransom note saying the dog would be hurt."

I poured the coffee into Mother's bone china cups and lifted the tray. Using my hip, I pushed open the kitchen door and went through the dining room to the parlor. At one time, it had been my favorite room. It was where Mother played the piano and Father read the newspaper in front of the fire, where the Christmas tree was decorated and the presents stacked. But that was a lifetime ago. Now the room seemed sad and cold. Steam rose from the coffee cups as I set the tray on the table.

"Who were you talking to?" Tinkie asked. Chablis sat on the horsehair sofa, ears perked at the kitchen door.

"Myself. Bad habit."

"You know your great-aunt

Elizabeth went off to Whitfield. And your aunt LouLane was such a dear, but all of those cats. How many was it, thirty-five cats? Now, she was your father's aunt, wasn't she? Folks thought she was a little strange, but everyone in town was hoping she'd be able to exert some proper influence over you. Not that your mother wasn't wonderful, she was just . . . different." She looked around the undusted room. "What was it your mother used to say? 'Give a damn!' Like a battle cry."

"Who's Ham?" I asked to distract her. My gaze wandered to Chablis. The dog would fit in my pocket.

"I shouldn't tell you about him," she said, biting her lip.

"Okay," I shrugged. I drank half my coffee, fast. It was cold in the parlor and I had fruitcakes to bake.

"He's been away for quite some time." She pressed her mouth shut, then sucked her bottom lip. It popped out of her mouth and I could imagine what effect that might have on the mysterious Ham. Tinkie wasn't a power brain, but she fully understood the cause and effect of winsome.

"Ah, a man from your past." I said it lightheartedly. Tinkie's fresh tears were unexpected. Also unexpected was the feel of tiny paws on my bare, chill-bumped legs. I picked the dog up and put her in my lap, glad of the tiny heat she generated.

"I hadn't thought of Ham in years," Tinkie confessed. "But Madame Tomeeka said he's coming back to Zinnia. I can't bear to face him, to admit that I married Oscar. That's what he said I'd do, and I did. But it was only because

Hamilton disappeared. He was just . . ." she shrugged her thin shoulders, "gone."

So, Tinkie had dallied with love and married security. Hell, it was tradition for women of our class. Tinkie and I had gone through school together. We'd attended Miss Nancy's cotillion and etiquette classes, had learned to smoke Virginia Slims cigarettes under the bleachers at the high school football game where we'd also practiced kissing. In essence, our entire lives were common knowledge. So who the hell was Ham?

"It might be helpful if you told me about him," I suggested, snuggling Chablis closer to me. The little dog really was quite warm.

The bone china cup rattled in its saucer. "I know I won't shock you, Sarah Booth," Tinkie said, doing that thing with her lip again. "Of all the Zinnia ladies, you're the most experi--sophisticated."

She meant that I, alone, had defied the societal dictates of the Delta Daddy's Girls. True enough, I had gone to Ole Miss. But there I had forsaken the tradition of university, and the tight-knit sorority structure that was an important part of matchmaking. I had made my friends outside the accepted order and defined myself as a rebel, a woman with dangerous tendencies--and probably some dread womb disorder that was affecting my brain.

"Spill it," I said.

"

Hamilton is one of the Garretts." She lifted her chin as she spoke, and it reminded me why I'd bothered to be friends with Tinkie. Underneath all of her craziness, she had a spine.

"The Garretts of Knob Hill?" I hadn't thought of them in years.

"Yes," she answered, chin leading.

"Tinkie," I whispered. The Garretts were notorious for all of the Faulknerian vices--drinking, killing, barn-burning, insanity, morbidity, raging jealousies, incest, and other dangerous passions. They were no different from any other family in our circle, but they had been caught out. "I thought the last of the Garretts had moved to

Europe ."

Paris was the choice of dissolute Southerners.

"He did." Her trembling hand placed the delicate china on the coffee table. "He came back, on occasion." She looked at her knees. "They still own Knob Hill, you know."