The Zombie Combat Manual (27 page)

Read The Zombie Combat Manual Online

Authors: Roger Ma

4. Finish with a neutralizing blow to the severed head.

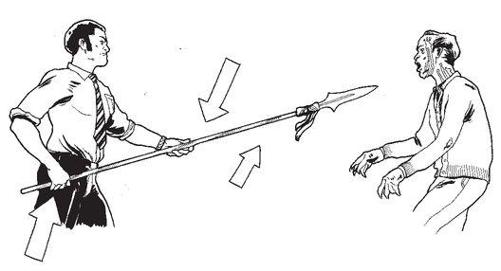

THE KABOB

TARGET AREA: MIDDLE CRANIAL FOSSA (MCF)/UNDERSIDE OF BRAIN

MOST EFFECTIVE WITH: STABBING/POINTED POLEARMS (SPEARS, PIKES,

AND LANCES)

TECHNIQUE: ONE OF THE MORE DIFFICULT TECHNIQUES TO EXECUTE, BUT

PERFECTLY SUITED TO A LONG-RANGE STABBING WEAPON

1. Hold your weapon near the middle and end of the shaft.

2. Aim the sharpened point of your weapon at the base of the ghoul’s throat.

3. Raise the point until it is under the chin, just inside the mandible.

4. Drive the weapon through the jaw and upward into the braincase.

Weapon Throwing

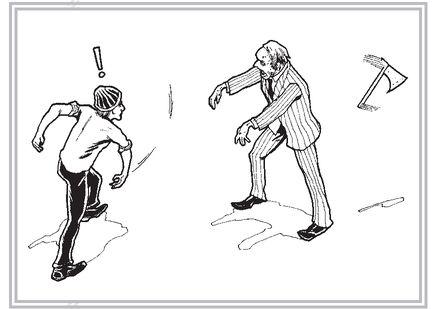

There may come a time when, as a result of media influence, poor advice, or simple overconfidence, you may be tempted to hurl your weapon at a ghoul in the distance in order to neutralize it. This is generally not recommended. Even in situations in which you witness a partner or family member in imminent danger, throwing your weapon is not a suggested option. There are several reasons why this technique is highly discouraged:

1.

Weapon design:

Armaments that are thrown are often explicitly engineered to do so. Weapons that are crafted to be hurled have better design, weight, and balance qualities that facilitate their aerodynamic properties. Although any weapon can be thrown, there is a high likelihood that an inexperienced thrower who tosses an ordinary edged weapon at an undead opponent will watch in dismay as the wrong end bounces harmlessly off the target’s body, if it hits the mark at all. Even if the throw manages to reach the target, remember that the blow is effective only if it penetrates the assailant’s white brain matter.

2.

Skill level:

Should you happen to acquire a throwing weapon, the skill required to consistently “stick” such a weapon requires years of dedicated training. If you fling your armament in order stop an impending attack on a loved one, you run the risk of hitting the person you seek to protect rather than your intended undead target. Remember that you are aiming for a small, moving target—the undead skull. Striking such a target with sufficient force to neutralize an attacking zombie would be a challenge even to a seasoned, professional knife thrower.

3.

Retrieval:

Throwing your weapon means losing your weapon, even if it is a temporary loss. Unless the armament you pitch is a backup to your primary weapon, being unarmed, even for a few moments, is a precarious risk during a zombie assault. If you follow our earlier recommendations of having a weapon handy for every combat range, you should have another means of protection available. In any case, having to spend time retrieving a thrown weapon means less time accomplishing other tasks, such as eliminating other undead threats in the vicinity.

Should none of these reasons convince you that throwing your weapon is a poor combat decision, try tossing your weapon at a stationary target at a variety of distances. Unless you achieve 100 percent accuracy in hit and penetration rate, you should probably avoid this tactic altogether. Use an appropriate long-range or ballistic weapon for distance neutralization, and keep your hand weapons where they belong—in your hand.

A Few Words on Decapitation

We have seen it depicted repeatedly on both the big and small screens—the conquering hero, facing off against a throng of opponents, draws his mighty saber. With a single, effortless swing of his blade, he lops the heads from his adversaries with ease. Were it only so easy.

Because decapitation has been so dramatically embellished in entertainment media, most of the population is unaware of how difficult it is to actually separate a head from its attached torso. Let’s examine the actual physical dynamics necessary in a decapitation attack. The average zombie neck is approximately fifteen inches in circumference. Not only must you slice through several different sets of muscle groups, you also must sever the spine and the cartilaginous rings of the trachea. Unlike what is depicted onscreen, only the most proficient and trained warriors are able to decapitate adversaries with a single swipe of the blade. For the average civilian, it may require up to six swings to completely chop through a zombie’s neck. Although long-range weapons are heavier and more likely to make decapitation easier, it is still an intensely strenuous act.

The death of Japanese author Yukio Mishima is quite possibly the best nonzombie example of how difficult the act of decapitation actually is. In 1970, as an act of defiance against the emperor, Mishima committed seppuku, ritual suicide, in the Tokyo headquarters of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces Eastern Command. In the tradition of this act, Mishima was to be decapitated at the end of the ritual. This important task was assigned to his friend, Masakatsu Morita. Morita was untrained in the use of a sword. After three attempts to decapitate his friend using the author’s own priceless samurai sword, Morita ultimately failed. Hiroyasu Koga, another friend who was present and a trained

kenshi

,

14

grabbed the sword and decapitated Mishima. Koga watched as Morita also committed seppuku, and then decapitated him as well. Why Mishima chose his untrained friend rather than the experienced Koga to execute the finishing act in the first place is unknown.

What can we learn from this historical incident? Reality can be a harsh teacher; although most of us would like to believe we could perform like the trained Koga, most of the population will fall into the Morita camp. This is nothing to be ashamed of. In due time and with the experience gained from even a single zombie encounter, your skill levels will steadily increase to where you may eventually perform like a skilled swordfighter. What is important is that you recognize that regardless of what you have seen onscreen, the actual act of decapitation is far more difficult than you can imagine.

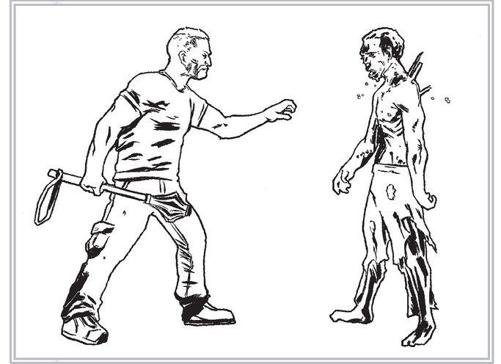

MEDIUM-RANGE/ MELEE COMBAT

SAFETY LEVEL OF ENGAGEMENT: MEDIUM

COMBAT SKILL REQUIRED AT THIS DISTANCE: MEDIUM

RISK OF INFECTION: 10-15%

Medium-range or melee combat is defined as engagement with the undead at a distance of 2 to 3 feet (0.6 to 0.9 meters) between opponents. The striking areas on the skull addressed previously in long-range combat are the same regions you should target at melee range. In fact, you may have a greater opportunity to attack these points given the improved control you will possess with a shorter, easier-to-handle weapon. For this reason, as well as weapon availability, terrain, and skill level, melee range is the most common distance at which undead combat takes place. Of all the possible undead combat ranges, melee combat requires the least amount of technical skill. It does, however, present its own unique set of challenges, the greatest being that you will be fighting at a distance where you are vulnerable to a ghoul’s reach.

Melee Combat Strategies

Just as in long-range combat, you should be aware of a few general strategies during any engagement that falls within the melee range.

The Fatal Funnel

The method by which you confront your undead opponent at melee range could significantly impact your level of vulnerability. The most common mistake untrained combatants make when engaging an attacker at this distance is walking into “the fatal funnel.” Those with law enforcement experience may be familiar with this term, as it traditionally describes the vulnerable area an officer faces when entering the doorway to a room or hallway containing potential threats. In relation to zombie combat, we’re describing the scenario of confronting an undead attacker at melee range from the most dangerous position—directly head on.