The Year of Finding Memory (2 page)

Read The Year of Finding Memory Online

Authors: Judy Fong Bates

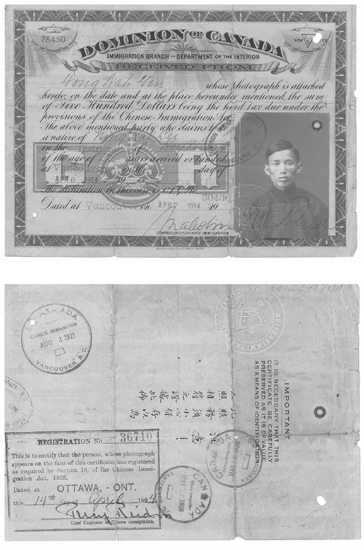

I turned this document over and saw the dates of my father’s entry and re-entries clearly stamped on the back. For thirty-three years while he travelled between China and Canada, his head tax certificate reminded him that he was unwanted in this country. Two deep creases showed where the certificate had been folded into thirds so it would fit inside an envelope. Other than these signs of wear, and a few tears along the edge, it was in pristine condition, considering that it had crossed the Pacific Ocean five times. But I should not have been surprised. My parents took exceptional care of their documents, not out of pride but fear—fear that if a

certain paper was lost or mutilated, they would not be allowed to enter one country or depart from another, or they would be unable to sponsor the immigration of family. Their existence would be suddenly nullified. In clean, black ink at the bottom of the certificate, covering a portion of my father’s chest, was the signature of the comptroller of Chinese Immigration, Malcolm M. Reid.

My father spoke to me many times about the head tax, his voice bitter.

Only the Chinese had to pay this money. No one else, Five hundred dollars to get into this country. Five hundred dollars I had to borrow.

But until I found the head tax certificate under his bed, I was not aware that it had remained in his possession. And now I was holding it in my hand, a worthless piece of paper, a priceless document, the cost of my happiness.

I took a deep breath and continued to look at the man in this picture. The paper felt heavy and my hands were trembling. A lump grew in my throat and I struggled to swallow. For as long as I had known my father, he had been an old man. But here he was, a youth, staring at me across time itself. At that moment it seemed as if we both had our lives ahead of us. If only I could find a way into the past and warn him.

ONE

I

would have preferred something a little more subtle, but the pink geraniums were past their prime, the leaves beginning to brown. The red ones, however, had leaves that were new and green, with clusters of buds yet to blossom. There was a limited selection of plants at the greengrocer’s, and I had walked up and down in front of the racks outside the store several times. I had contemplated other flowers this year, but for as long as I could remember, whenever my family visited the graves, they took geraniums. It was hard to know whether they had been chosen because of their low price or their symbolic value or because of superstition. Like so many rituals from my childhood, the longevity of the tradition had taken on a significance of its own, and to depart from an established way of doing things might pose a risk. We had always done it this way. And nothing bad had happened. So why change? Why risk the wrath of the gods? I picked the four best plants, and my husband put them in the back of our station wagon.

Michael and I had just picked up my brother Shing from his suburban home north of Toronto for the annual visit to my parents’ graves at Mount Pleasant Cemetery. On that particular day in early June of 2006, the sky was cloudless and the air in the city felt thin. I noticed that every year, no matter which day we chose for the grave ceremony, the sun shone. I no longer bothered to check the weather forecast.

Shing is actually my half-brother, a son from my father’s first marriage. He is a gentle man who possesses a quiet dignity. When he left China for Hong Kong in 1950, he was twenty years old. A year later, when he arrived in Toronto, a village uncle who owned a restaurant gave him a job as a waiter. Eventually he found a position at the post office sorting mail. He regards himself as fortunate to have a government pension that has given him and his wife a modest retirement. I have a photograph of him taken in the early fifties. Dressed in a pale summer suit, he is leaning against a shiny, black car, a beaming smile on his face. I once asked him if the car belonged to him or a friend. He laughed and said he had no idea who owned the car.

My parents’ plot is marked by a pink granite headstone, with their names boldly engraved in English and Chinese. Unlike the older, established part of Mount Pleasant, where the graceful canopies of tall, elegant trees provide shade and refuge, the area where my parents are buried is like a suburb on the edge of town, with sun-baked expanses of lawn, trees and shrubs not yet mature. The graves have names like Wong, Lee, Choy, Seto and Fong.

Shing and I had filled our watering cans at the nearby tap. Michael was crouching in front of the stone, digging two holes with a trowel. As soon as he finished, he poured water into the holes and waited for it to soak in. He then removed the two geraniums from their pots and planted them. He rinsed the gravestone with the leftover water, and with a small twig he cleaned out any moss that had grown inside the engraved characters. Lastly, he pruned the conical cedar bushes on either side of the grave. Every year my husband performed this custodial role for the graves of people who weren’t his parents while their children watched. Once Michael completed the tidying, my brother and I arranged the offering of oranges, dumplings and cups of tea on the grass. I had never been able to do this without thinking of it as a picnic for the dead. Shing then handed me a sheaf of spirit money, which he had purchased in Chinatown. Every colourful bill was printed with denominations in the millions and billions, money needed for bribing evil spirits in order to ensure safe passage into the afterlife. I stuffed the paper inside a large coffee tin while Shing made up three bundles of incense sticks. Michael struck a match, lit the sticks, then tossed the match into the can, igniting all those bills.

I am not a religious woman. Nevertheless, as a good Chinese daughter, I have performed these rituals every year since my father’s death—but I have never left with a sense of peace, unable to escape the fact that unhappiness permeated my parents’ marriage. No contented sighs over lives that had been filled with challenges but were ultimately well lived.

It was impossible not to think about their loneliness and about my father’s sad end. After all these years, I still tasted a residue of shame in my mouth. As I watched Shing bow three times in front of the headstone, with the incense sticks still in his hands, I wondered if he was thinking the same thing. The memories that no one in my family dared to voice. I watched Shing as he jammed the smouldering incense into the earth next to the flowers. Was he also haunted by our father’s death? Or was he thinking ahead to China, a land we had not seen for more than fifty years?

Earlier in the year, my half-sister Ming Nee, my mother’s daughter from her first marriage, had proposed a family trip back to China that would include her, our brothers Shing and Doon—another son from my father’s first marriage—and me. Her husband was a university professor, and through his work they had travelled frequently over the years to the Far East. She had been back to visit our family in China several times. Although Ming Nee had initiated this journey home, it turned out that she would be unable to accompany us, as our needs and her husband’s schedule were incompatible. Nevertheless, her suggestion had planted an idea that my brothers and I could not ignore: we knew that the time had come for us to return. I wanted to be with my brothers for this homecoming, and the trip would also include Michael and Shing’s wife, Jen, and Doon’s wife, Yeng.

When Shing and Doon had left China, they were young men looking to the future. How vivid were those memories of growing up across the ocean? My brothers had left

behind in China a sister in her early twenties and an older brother in his early thirties, each married with young children. The brother was now dead and the sister was seventy-six and widowed. The last time we saw each other, I was three. It was shocking how little I knew about these half-siblings. If my sister had passed me on the street, I would not have recognized her.

Shing and Doon, though, sent money to the family in China every year. They were close in age to this sister and had grown up with her in a village I had never seen. They watched out for each other after their mother died during the Second World War and their father was stranded on the other side of the world. I knew that my role in this return journey would be peripheral. They were returning to a homeland; I would be exploring a foreign country, a place of great curiosity but no real emotional attachment. My home was here. I was a happily married woman, with a teaching career that had lasted more than twenty years and had achieved some professional success as a writer. I had raised two healthy, independent daughters, the oldest married and expecting her first child. I owned my own home. I had survived my parents’ unhappy marriage and my father’s tragic death. In China I would be more like my Anglo-Canadian husband—a tourist, sitting on the sidelines, watching someone else’s momentous occasion.

Shing finished paying his respects and indicated to Michael and me that it was our turn to pray. I bowed three times, but I was no longer thinking about my parents. I was thinking of the deep anticipation that my brother must have felt when

he first decided to make the journey to China. It was an anticipation I would never know. A twinge of envy pricked at my heart.

The food that we had set in front of the gravestone was packed away in a cooler and stored inside the station wagon, ready to take back to Shing’s house. We climbed into the car and drove across the cemetery to where Second Uncle was buried. His grave is marked by a tiny, rectangular grey stone, chiselled with just his name and date of death in Chinese characters. This area has only small, flat memorial markers, and like my uncle’s the inscriptions are all in Chinese. Every year we needed to wander for several minutes to find his marker because it was always overgrown with grass. But this year we found it quickly; Michael had remembered that there was a yew tree nearby, with a distinctive shape. Second Uncle had brought no children to the Gold Mountain, no son or daughter to honour his grave. Other than the fact that he was an older brother who had come to Canada with my father in the early part of the twentieth century, as a child I knew almost nothing about him, not even his name—and by the time my mother joined my father in Canada, this man had been dead for several years.

But every year Shing reminded me to buy flowers to plant for Second Uncle. I stood looking at his gravestone and thought about my parents’ resting place—their upright, shining, granite headstone proudly proclaiming their status in Canada. And yet it was Second Uncle’s humble marker that spoke the truth. I was only too aware of how sad and

difficult my parents’ lives had been in this country that remained foreign to them until they died.